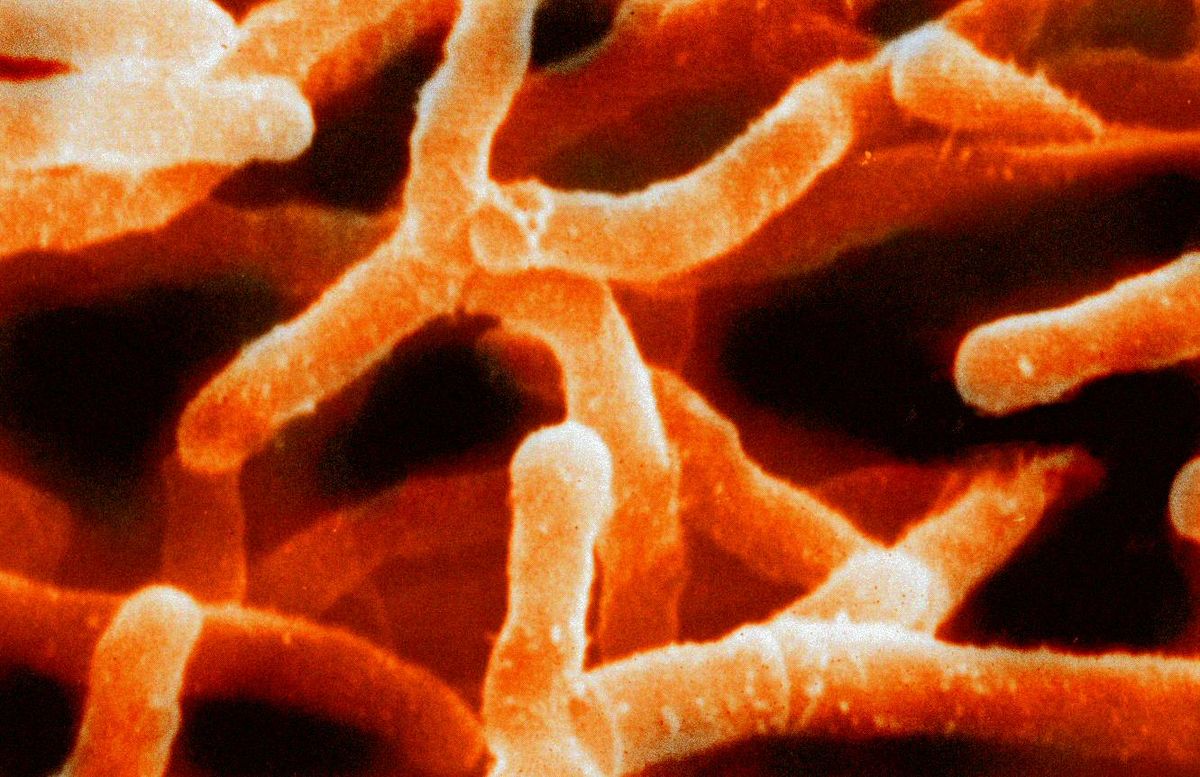

Researchers have developed a method to spur the production of new antibiotic or antiparasitic compounds hiding in the genomes of actinobacteria, which are the source of drugs such as actinomycin and streptomycin and are known to harbor other untapped chemical riches.

This was in the attempt to overcome the age-old problem that confronts those hoping to study and make use of the countless antibiotic, antifungal, and antiparasitic compounds that bacteria can produce. “In laboratory conditions, bacteria don’t make the number of molecules they have the capability of making and that is because many are regulated by small-molecule hormones that aren’t produced unless the bacteria are under threat,” said Satish Nair, Professor of Biochemistry, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Nair and the team wanted to determine how such hormones influence the production of antibiotics in antinobacteria. By exposing the bacteria to the appropriate hormone or group of hormones, the researchers hope to spur the microbes to produce new compounds that are medically useful.

The team focussed on avenolide, a hormone that is more chemically stable. Avenoide regulates the production of an antiparasitic compound known as avermectin in a soil microbe. A chemically modified version of this compound, ivermectin, is used in a treatment for river blindness, a disease transmitted by flies.

The researchers used the process of genome mining and identified 90 actinobacteria that appear to be regulated by avenolide and other hormones of the same class.

The researchers discovered that when the hormone binds to the receptor, it loses its ability to cling to DNA. This allows the organism to churn out defensive compounds like antibiotics.

Source: ANI