Kadhalikka Neramillai – a lighthearted film on the surface that espouses the Dravidianist question of – “Is marriage really necessary?”

Directed by Kiruthiga Udhayanidhi, the film has a “puratchi pudhumai penn” (a revolutionary modern woman) at its helm, and yes, she is not a random girl, but a TamBrahm.

An analysis:

This rom-com has Shriya Chandramohan as its central character – she has a boyfriend, registers her marriage months before the engagement – (WHY?), drinks, has premarital fun, doesn’t know how to wear a saree, smokes after a breakup, etc.

In summary, a modern-day career-centric, jolly good woman. No issues. But is she a “random” modern-day woman? Nope.

In egalitarian EVR (read Periyarist) land where there are no caste surnames, the film portrays her family as TamBrahms with no hesitation whatsoever.

Shriya finds out, days before her “official” engagement, that her legally wedded husband is cheating on her.

So, in a case of role reversal, she drinks, and tries smoking in an attempt to move on, like “men”. Her father is sort of cool with it. Her aunt (played by Vinodhini) jokingly hints at having “properly” smoked before.

Just moments before, there’s a deliberate scene where the aunt calls Shriya’s father “Athimber” (a word used by Dravidianists to mock TamBrahms)

But why this depiction of community is necessary? Read on.

Even though Shriya is modern and calls off her engagement, her family members are upset, and yes, they are rituals/Shastra-obsessed “regressive” folks who think that education makes women arrogant.

The subtle implication: TamBrahm mamas would blame women’s education for becoming cultural degenerates. Now it starts to make sense why her caste was represented transparently.

Dejected, Shriya just wants a kid without marriage, so she gets IVF treatment in Chennai, from an anonymous sperm donor (who is Jayam Ravi).

While pregnant, she uses her relative’s contact to break hospital rules (!!!), retrieves details about the sperm donor, and travels to Bengaluru to find out details about the “dad”.

But it is a dead-end, as Jayam Ravi had faked his name and gave a fake address of a pub as his own. In Dravidaverse, this logic applies. Anybody can donate sperm by mentioning pub addresses as your own and the sperm banks don’t bother verifying at all. They don’t even verify your name. It is cinematic liberty certified by White Dwarf (pun intended), you see.

In a chance encounter at the Bengaluru pub, she meets Jayam Ravi (whose community is not mentioned) for the first time and his 2 friends – the gay Vinay called Sethuraman, (a half Malayali), and Yogi Babu – who is named Gowda. Just Gowda.

Implication: Why can’t you Kannadigas learn from the egalitarian TN?

In the real world, if a girl just meets a stranger guy and his 2 friends at a pub who offer dinner at the guy’s place, what would the girl do? Politely excuse herself or…?

But no, Shriya is a happy-go-lucky TamBrahm woman – she not only goes to Jayam Ravi’s home with his 2 strange friends in a car, she also dines at his place and gives a certificate for how good a fish Jayam Ravi’s dad has cooked.

Only if you believe all this will you get your 200 bucks. Will you eat it or…?

The second half cuts to 8 years later, where the independent, career-oriented single mom Shriya who lives with her aunt raises a boy child, admirably well.

In a happy coincidence, Jayam Ravi and Shriya’s paths cross again, where JR fills the missing dad role in the son’s life, without realizing that he’s his biological father. It all ends well with both Shriya and Jayam Ravi getting together without ever realizing their shared secret.

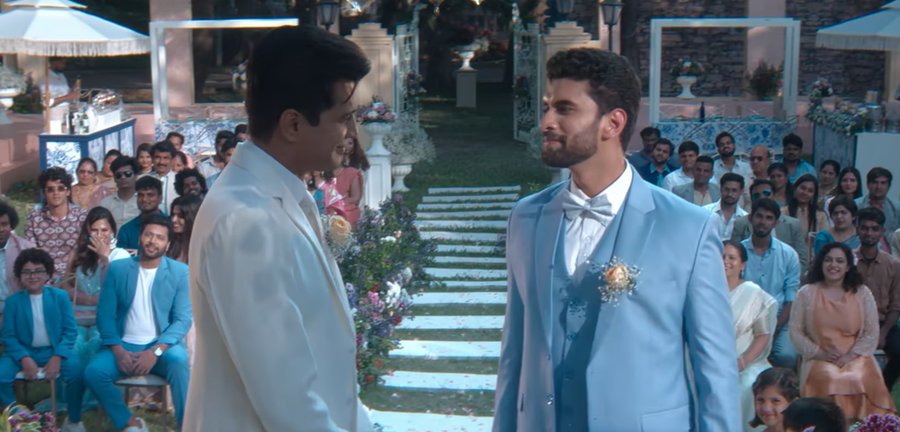

Sethuraman gets married to his male partner, in a Christian-style wedding (they also have a girl child – born of Sethu). But, in the very next scene, the straight Shriya says she doesn’t want a “marriage” with Jayam Ravi, as their companionship suffices. Oh, the irony.

While on the surface this looks like a “feel good” rom-com, it actually espouses the Dravidianist question of “Is marriage really necessary?” – a question asked since EVR times, and repeated by Dravidianist ideologues like Vairamuthu, etc.

While they are free to make films espousing their ideology (however hypocritical/dangerous they may be), what is the need to identify the community of the heroine?

Irrespective of your political inclinations, ask this question:

Why are all feminist, revolutionary women in Tamil films represented from this comm alone? Don’t Dravidianists have any admirable feminists among them? Asking this question is the starting point to understand Dravidianism and Dravidianists.

Tamil Labs provide high quality Tamil Content written interestingly in English.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.