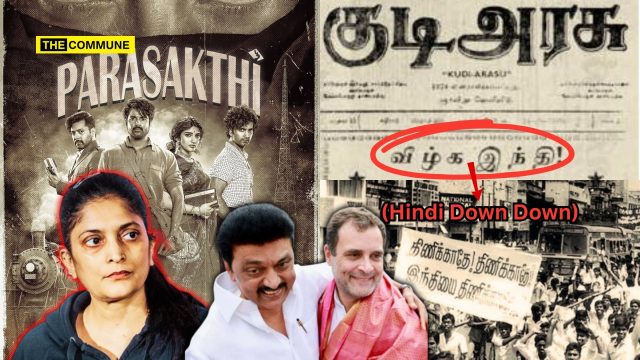

Filmmaker Sudha Kongara’s upcoming period political drama Parasakthi, headlined by Sivakarthikeyan, has sparked intense political discussion even before its release, with growing focus on whether the film will foreground the historical role of the Indian National Congress in imposing Hindi on non-Hindi-speaking states.

Set against the backdrop of the 1965 anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu, Parasakthi is nearing completion and is slated for a Pongal 2026 theatrical release. An immersive promotional installation titled World of Parasakthi is currently being held at Valluvar Kottam, featuring recreated 1960s Madras streets, period props, and character exhibits tied to the film.

While early speculation framed Parasakthi as a film targeting contemporary language politics, it is argued that the film’s core theme could point squarely at Congress-era Hindi imposition, particularly under Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi.

While the film is believed to talk about the 1965 anti-Hindi agitations, it is making the viewer curious if the film will actually talk about the largely forgotten historical sequence: that the push for Hindi as a unifying national language began under Congress leadership, not the BJP, as is being projected by the Dravidianists.

Mahatma Gandhi is the one who had initiated the Hindi Prachar Sabha, in Madras (now Chennai). The Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha was founded in 1918 specifically at Madras by Mahatma Gandhi to propagate Hindi among non‑Hindi speakers in the southern provinces, and he served as its founding president.

Gandhi personally pushed the Hindi‑prachar campaign in Madras: he sent his son Devdas there as the first pracharak, first Hindi classes were held at Gokhale Hall in George Town, and Gandhi made multiple trips to Madras and other southern centres to promote learning Hindi as part of Congress’s national‑integration vision.

This effort was later carried forward by Nehru and formally institutionalised during the tenure of Indira Gandhi. The Constitution (Article 343(1)) itself envisaged that Hindi would become the sole official language of the Union after a 15‑year transition ending in 1965, with English to be used only during that period; this provision was adopted in 1949, before Indira Gandhi’s tenure as PM. As 1965 approached, the Congress government at the Centre (by then under Lal Bahadur Shastri) initially prepared to let Hindi become the primary Union language, triggering the massive anti‑Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu.

The widespread belief in Tamil Nadu, that only the BJP imposes Hindi while the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam resisted it, oversimplifies history. The 1965 agitations were directed primarily against Congress rule at the Centre, not against the BJP, which did not exist in its current form at the time.

The Bengali Language Movement of 1952 in East Bengal and the subsequent 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War are said to have served as an international warning against language imposition, and the experience of East Pakistan was frequently cited by Indian commentators and some political leaders as a “bitter lesson.”

However, contemporary accounts of 1965 indicate that the immediate trigger for New Delhi’s retreat from plans to make Hindi the sole official language was the intensity of the anti-Hindi agitations in Madras State itself. Widespread protests, suicides, arson, riots, and a near-total shutdown of the State compelled Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri to publicly assure the continued use of English alongside Hindi.

While the linguistic conflict in East Pakistan had already demonstrated how enforced language policies could fracture a nation, it was the scale and violence of the 1965 protests in Tamil Nadu that forced the Congress-led government to act decisively. Critics argue that this reassessment of language policy stemmed less from sustained political pressure by the DMK and more from the immediate fear of social unrest and national instability, reinforced by the cautionary precedent of Bangladesh.

View this post on Instagram

Against this backdrop, will Parasakthi be a film that challenges the dominant political narrative around language politics? Despite the film’s apparent critique of Congress-led Hindi imposition, it is being actively promoted by DMK-aligned entities, including Red Giant Movies.

Whether Parasakthi explicitly reframes the anti-Hindi agitations as a movement against Congress, and not the BJP, remains to be seen. However, the debate surrounding the film has already reopened questions about who imposed Hindi, why it was resisted, and how language politics in Tamil Nadu have been reshaped and retold over decades.

The question to be asked is this – will Sudha Kongara’s Parasakthi unsettle the DMK–Congress alliance by confronting inconvenient history, or will it be repackaged to reinforce a contemporary narrative that shifts blame onto the BJP?

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.