On 7 November 2025, India marked the 150th anniversary of ‘Vande Mataram’, the slogan that awakened the nation against colonialists.

The six-stanza song, written by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee in 1875 and published in his 1882 novel Anandmath, became a powerful symbol of India’s freedom struggle. The hymn personified India as a mother figure, fierce like Durga, prosperous like Lakshmi, and wise like Saraswati. However, by the 1930s, some Muslim leaders objected to these depictions, arguing that worshipping the nation in the form of Hindu goddesses conflicted with their religious beliefs.

The controversy over why parts of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s hymn were omitted has resurfaced in this context, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP accusing the Congress of “pandering to communal sentiments”.

What Nehru Told Jinnah

According to archival records and correspondence, the controversy reached its peak in late 1937. On October 25, 1937, Jawaharlal Nehru wrote to Muhammad Ali Jinnah explaining that only the first two stanzas of Vande Mataram would be used at national gatherings because “the later portions contain certain allusions which might offend the susceptibilities of our Muslim friends.”

What Nehru Told Netaji

In a separate letter to Subhas Chandra Bose, Nehru acknowledged that “the background of Vande Mataram is likely to irritate the Muslims,” though he personally felt that “the whole song and all the words in it are thoroughly harmless.”

What Nehru As Congress Working Committee President Said

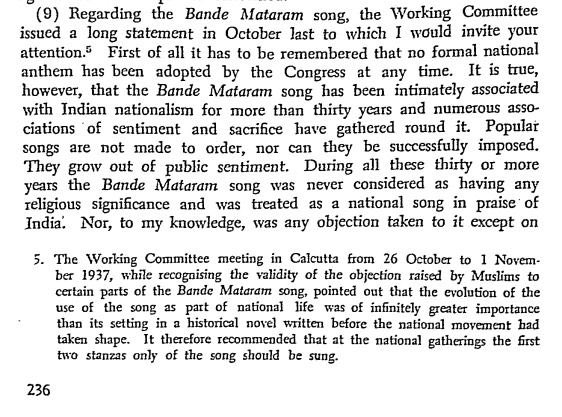

The Congress Working Committee, which convened in Calcutta between October 26 and November 1, 1937, acknowledged the Muslim community’s objections to Vande Mataram as valid and recommended that only the first two stanzas be sung at official national functions.

At its meeting in Calcutta from 26 October to 1 November 1937, the Congress Working Committee formally addressed the issue. It recognised the objections raised by sections of the Muslim community and observed that while the song had “become intimately associated with Indian nationalism,” certain stanzas containing “allegorical references” should not be used “on national platforms or occasions.”

The committee, therefore, recommended that only the first two stanzas which contain no direct religious imagery, be sung at national gatherings. These lines describe the motherland’s natural beauty and nurturing power, without referring to specific deities.

The Congress resolution stated: “Taking all things into consideration, therefore, the Committee recommends that whenever Vande Mataram is sung at national gatherings, only the first two stanzas should be sung.”

Nehru defended the move, arguing that popular songs “grow out of public sentiment” and should not be imposed in ways that might alienate sections of society. “To compel large numbers of people to give up what they have long valued and grown attached to,” he wrote, “is to cause needless hurt and injure the national movement itself.”

Why were paragraphs omitted from Vande Mataram?

Because Jawaharlal Nehru himself explained to Jinnah that certain stanzas were “objectionable to Muslims.”

In a letter to Jinnah dated 25 October 1937, Nehru wrote that only the first two verses of Vande Mataram would be used… pic.twitter.com/10Bz4XTDeV

— Amit Malviya (@amitmalviya) November 7, 2025

Nehru stated that the Congress Party chose to accommodate Muslim objections to Vande Mataram as it sought to represent all sections of India, including those with extreme views, under the banner of the “All India Congress.”

“There are certain words in it which certainly can be taken objection to by some. If so we have no sufficient answer to give to those who object. We do not very much mind the objections of some people who do it just for the sake of it,” he remarked.

He said the Working Committee’s decision followed detailed discussions meant for the entire nation, not just Bengal, and blamed “honest misconceptions” for the controversy surrounding the song.

Rather than defending Vande Mataram, Congress chose to appease its Muslim voter base by declaring that only the first two stanzas were suitable for national use, as the rest contained “ideology, imagery, allegory” unacceptable to some groups.

Nehru also downplayed the song’s importance, claiming he could not “enthuse over an ideology, Hindu or Muslim,” as such associations “diverted attention” from its meaning.

While conceding that the objections were largely misplaced, Nehru and the Congress upheld them in the name of “secularism,” effectively sidelining Hindu sentiments to avoid offending minorities.

What Nehru Told Urdu Poet Ali Sardar Jafri

In a letter dated September 1937 to Urdu writer and poet Ali Sardar Jafri, Nehru addressed the growing controversy over Vande Mataram, asserting that the song was not officially linked to the Congress. However, he admitted that it had become deeply tied to the spirit of India’s independence movement and held emotional significance for the people.

He wrote, “The Congress has not officially adopted any song as a kind of national anthem. In practice however the Bande Mataram is often used in national gatherings together with other songs. The reason for this is that 30 years ago this song and this cry became a criminal offence and developed into a challenge to British imperialism.”

Nehru explained that countless Indians had suffered for raising this slogan, and over time, it came to represent resistance to British rule and a symbol of nationalism. He added, “I do not think anybody considers the words to have anything to do with a goddess. That interpretation is absurd. Nor are we concerned with the idea that the author of the book, which contains this song, had in his mind when he wrote it, because the public does not think on these lines.”

To reinforce Congress’s secular image, Nehru maintained that the lyrics were “harmless” and unobjectionable, yet argued that Vande Mataram was unfit to be treated as a national song. He reasoned, “It contains too many difficult words which people do not understand and the ideas it contains are also out of keeping with modern notions of nationalism and progress… We should certainly try to have more suitable national songs in simple language.”

While distancing the Congress from the song and calling it too complex for national use, Nehru softened his stance by acknowledging, “But great songs and anthems cannot be made to order. It requires a genius for the purpose… I suppose in time we shall get something good. Meanwhile, there is no reason why we should not give full permission for the use of the Bande Mataram as well as other favoured songs which many people have come to associate with our struggle for freedom.”

A hundred and fifty years since it was first written, Vande Mataram continues to echo in the hearts of millions — a timeless call that once stirred a nation to rise against foreign rule. Yet, its marginalisation by the Congress leadership in the name of “secularism” remains one of the earliest examples of political appeasement dressed up as inclusivity. What Nehru and his colleagues failed to understand was that Vande Mataram was never merely a song — it was the soul of India’s awakening, a hymn that united people across faiths under the banner of Bharat Mata.

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.