On 25th June 1822, Thomas Munro, the then Governor-General of Madras province commissioned an extensive of survey of the indigenous education system in his province. He ordered the district collectors to collect information on the state of village schools. Around the same time (1819-1827), the Governor-General of Bombay, Mountstuart Elphinstone gave orders to the Commissioner in Deccan and to the district collectors of Gujrat and Konkan to report on the state of education in their respective districts. A similar exercise was carried out in Bengal in the 1835 when Governor-General of Bengal William Bentnick appointed William Adam to survey the indigenous education systems in the regions.

In all these surveys, it was found that neither was the Manu Smriti taught nor was it used as a syllabus material.

The early European travellers to India have all reported repeatedly that the country overall, was working in a sustainable manner with a decentralized system of administration in place where most of the disputes were settled at the village level itself, by and large, to the satisfaction of all.

Such a dispute redressal system, surprisingly for the British onlookers, was not based on any one legal book of the land. This was indeed surprising for the British administrators, because back home in England, justice was dispensed based on a legal book. Thus, William Jones, who served as a pusine judge at the Supreme Court of Judicature established at Fort Williams in Bengal, began the search for a book on laws through which they can administer the native subjects.

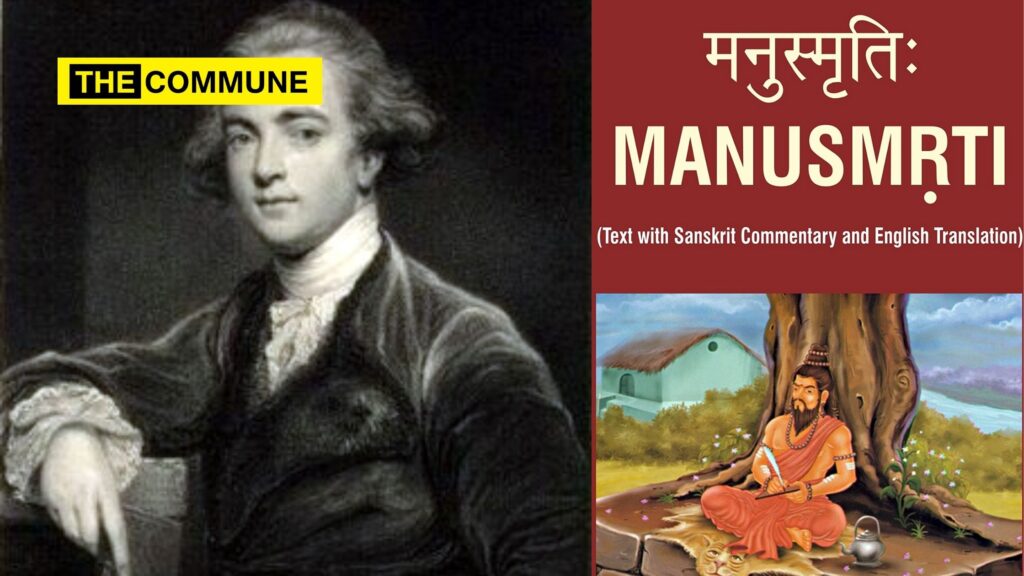

William Jones’s search for a book of law for the Hindus, exposed him to the world of Smritis and the decided that Manu Smriti was the legal code, best suited to be practiced for the Hindus in India. He took out components from Manu Smriti, and incorporated it into the law book of India.

However, he didn’t have any problem with finding a law book for the Muslims because they had only one book – the Quran and the Hadiths which draws from the Quran.

He thus made a separate digest of Hindu and Muslim laws.

Even today one can find the Marble Frieze of Sir William Jones in Chapel of University College, Oxford, inscribed with the words, “HE FORMED A DIGEST OF HINDU AND MOHAMMEDAN LAWS”

The marble frieze depicts William Jones learning law from 3 Indian scholars.

For this effort, the British referred to him as “Justinian of India”.

It was this singling out of Manu Smriti by Sir William Jones that gave Manu Smriti the pre-eminent position in favour of other Smritis. Until then, a host of other smritis had equal status and were used by different communities, in different places and in different eras, depending upon the need and applicability of the Smriti.

The comment of Warren Hastings, an English statesman , confirms how, Manu Smriti was not the only and standardized law book of India and how, India had been following many law books until William Jones standardized Indian law based on Manu Smriti.

This standardization by William Jones even sowed seeds of hatred among different communities of India, especially towards the Brahmins, as if it was the Brahmins who had imposed Manu Smriti on the society.

In fact, the law codes, Smriti, change regularly with periods of time, Yuga. It is mentioned in Manu Smriti that it was created for a particular period in societal evolution, namely the Krta Yuga (1,72,800 years ago).

We are now living, two Yuga thence, in the Kali Yuga and one of the suggested referral law code texts for the Kali Yuga is Parasara Smriti, which too remains unheard of for today’s practicing Hindus.

Sir William Jones took Manu Smriti out of obscurity in 1776. It was this Manusmriti that Dr. Ambedkar burnt on December 25, 1927.

Since the time William Jones came out with the translated Manu Smriti, for the past 200 years and more, the codes of suggestive law in this Smriti, meant for a different Yuga, have continued to stay imposed on the Indian polity.

This erroneous perception and the myth has to be cleared first, for clarity in the political dialogues of the current decade.

The rabble rousers who hide behind Dr. Ambedkar’s coat, should know that even Dr. Ambedkar was careful enough to not demean the entire Sanatana Dharma in the name of being progressive. As much as he hated Manu, he did acknowledge the high respect given to women in ancient India.

That at one time a woman was entitled to upanayana is clear from the Atharva Veda, where a girl is spoken of as being eligible for marriage, having finished her Brahmacharya. From the Shrauta Sutras, it is clear that women could repeat the mantras of the Vedas and the women were taught to read the Vedas. Panini’s Ashtadhyayi bears testimony to the fact that women attended Gurukul (college) and studied the various Shakhas (Sections) of the Veda and became expert in Mimamsa. Patanjali’s Maha Bhashya shows that women were teachers and taught Vedas to girl students. The stories of women entering into public discussions with men on the most abstruse subjects of religion, philosophy and metaphysics are by no means few. The story of public disputation between Janaka and Sulabha, between Yajnavalkya and Gargi, between Yajnavalkya and Maitrei and between Sankaracharya and Vidyadhari shows that Indian women in pre-Manu’s time could rise to the highest pinnacle of learning and education. That at one time women were highly respected cannot be disputed. Among the Ratnis who played so prominent a part in the coronation of the King in ancient India was the queen and the king made her an offering, as he did to the others. Not only the king-elect do homage to the queen, he worshipped his other wives of lower castes. In the same way, the king offers salutation after the coronation ceremony to the ladies of the chiefs of the Srenies (guilds). This is a very high position for women in any part of the world.

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writing and Speeches, Vol.17: Part-2, Ed. Vasant Moon, Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra, 1995 (p.122)

He even quoted Manu when the Parliament was debating on the Hindu Civil Code Bill to make a point on succession and property rights.

There is no doubt that the two Smritikars whom I have mentioned — Yagnavalkya and Manu — rank the highest among the 137 who had tried their hands in framing Smritis. Both of them have stated that the daughter is entitled to one-fourth share. It is a pity that somehow, for some reason, custom has destroyed the efficacy of that text: otherwise, the daughter would have been, on the basis of our own Smritis, entitled to get one-fourth share.

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writing and Speeches, Vol.14 [Part One], , pp.280-1

So, before Thirumavalavan, Periyarist cabals and other Hinduphobic elements call for the ban on Manusmriti, a text that 99% of the Hindus do not even care about, let them at least make an effort to what Dr. Ambedkar has said about it in different writings and speeches.

Hindus should realize that when Dr. Ambedkar critiqued Manu Smriti he did not spew venom on a particular faith or community unlike these foul mouthed coolies of breaking India forces.

(With inputs from Autobiography of India: Breaking the Myths, Volume 2, by Dr. K. Hari and Dr. K. Hema Hari)

Views expressed here are author’s own.