A “unique aspect” of the Sabarimala pilgrimage is the tradition of stopping at the Vavar mosque in Erumeli, an apparent nod to a supposed friendship between Ayyappa and Vavar, a Muslim figure portrayed as a warrior, pirate, or even a mystical incarnation. However, a closer look at the historical and cultural basis of the lore of Vavar reveals a different story, one that lacks historical evidence and that many now argue may be a recent interpolation rather than an ancient, integrative tradition.

Who Was Vavar? What Are The Roots Of The Myth?

The story of Vavar Swamy as a close associate of Ayyappa has multiple, often contradictory, versions. Some tales describe Vavar as a foreign invader defeated by Ayyappa, while others cast him as a merchant or a warrior who migrated from distant lands. Some legends assert that he was a divine figure – Vapuran alias Vapar – an incarnation of Lord Shiva turned Muslim warrior who eventually aided Ayyappa in battles. These conflicting stories point to the fact that Vavar’s identity is largely based on oral lore, and this lore appears to lack foundational historical references, particularly before the 19th century.

In fact, despite Vavar’s association with Ayyappa in recent narratives, there is no mention of Vavar in older Hindu texts or Tamil literature. Ayyappa’s origins as Dharmashasta, a deity mentioned in various Puranas and ancient Tamil inscriptions from as early as the 3rd century CE, predate Islam by several hundred years. Similarly, iconographic evidence, such as murtis (sculptures) of Ayyappa/Shasta, were created centuries before Islam’s birth.

https://twitter.com/BharadwajAgain/status/1576814794031919104

https://twitter.com/BharadwajAgain/status/1576819408982269952

This timeline disparity casts doubt on the historical possibility of an Islamic figure closely linked with Ayyappa’s worship, as Islam emerged over 1,300 years ago—well after the period in which Ayyappa devotion was already flourishing in South India.

How Dramatization Aided In “Establishing” This So-Called “Tradition”?

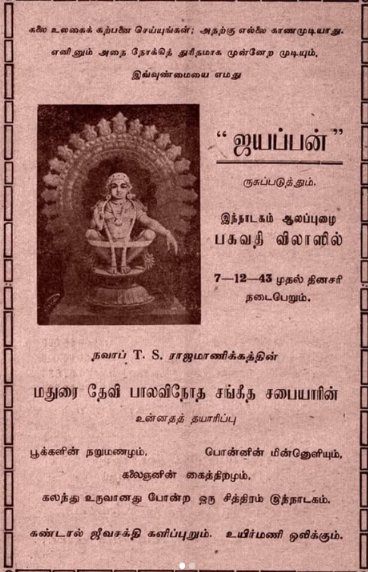

The myth surrounding Vavar and the practice of visiting the Vavar mosque during the Sabarimala pilgrimage can be traced back to a dramatization in the early 1940s. Nawab Rajamanickam Pillai, a renowned dramatist, was requested to adapt the story of Lord Ayyappa into a play while visiting Alappuzha. Initially hesitant, he was so moved by the tale that he created the play Swamy Ayyappan and personally undertook the Sabarimala pilgrimage.

However, in crafting his script, Pillai incorporated elements from both mythological and historical accounts, blending stories of the deity Ayyappa with the king Ayyappa. One significant addition was the character of Vavar, a pirate leader who, after a confrontation with Ayyappa, became his devotee.

This dramatic portrayal of Vavar’s transformation was intended to serve as an emotional high point in the play, but it inadvertently became a defining narrative for many devotees.

This is a notice about a play that altered the portrayal of Ayyappa devotees..!!

It was a drama staged in 1940 by Nawab Raj Manikya Pillai and M. N. Nambiar.

In this play, M. N. Nambiar played the role of the king of Pandalam. One of the scenes they included as an interlude… pic.twitter.com/AYPQvL5GRu

— Pratheesh Viswanath (@pratheesh_Hind) November 4, 2024

The power of the play left a lasting impression, leading audiences to believe that visiting the Vavar mosque at Erumeli was an integral part of the Sabarimala pilgrimage. This practice, however, has been dismissed by various authorities, including Nambiar Guruswamy M. N. Nambiar and other ancient gurus such as Punalur Subramania Iyer and C. V. Srinivasa Iyer, who emphasized that this tradition was not part of the original puja vidhanam. Historical texts like Sri Maha Shasthu Pooja Kalpam (1938) also clarify that Vavar is not a Muslim figure but a Shiva Bhuta, a guardian deity, and companion of Lord Ayyappa.

As discussions intensify over the identity of the guardian deity at Sabarimala—whether it is Vavar or Vapuran—a key historical reference has surfaced: Sri Maha Shasthu Pooja Kalpam. This authoritative text, written in Kollam Year 1114 (1938 AD) by Yogi Baladandayudhapani Swamikal, has been examined by Brahma Shri Vittala Ahithanal and published by Jayachandra Book Depot, Chalai, Thiruvananthapuram. At 86 years old today, this text holds significant relevance for devotees.

The Sri Maha Shasthu Pooja Kalpam makes the following unambiguous statement:

“Some mistakenly believe Vapuran to be a Muslim figure. This misconception likely arises because of the Vavar mosque in Erumeli. However, Vapuran is, in fact, a Shiva Bhuta, a guardian deity, and a parivara devata (companion deity) of Lord Ayyappa.”

The book further provides Vapuran’s root mantra: “Om Angarakshakaya Maha Shastru Parivaraya Vapuraya Swaha”

The text also elaborates on Vapuran’s form as a recognized deity, integral to the worship traditions associated with Lord Ayyappa. Vapuran is described as the protector of Vapurakkunnu, emphasizing his established role in Sabarimala’s spiritual heritage.

This rare book, predating Sabarimala’s widespread prominence, offers clarity: it is not “Vavar” or “Vaparan,” but Vapuran, the guardian deity residing at Vapurakkunnu.

Dear Ayyappa Swami devotees,

As debates heat up about whether the guardian at Sabarimala is Vavar or Vapuran, a key reference has emerged: Sri Maha Shasthu Pooja Kalpam, written in Kollam Year 1114 (1938 AD). This significant book, authored by "Yogi Baladandayudhapani Swamikal,"… pic.twitter.com/vyKzyqhvZh

— Pratheesh Viswanath (@pratheesh_Hind) November 14, 2024

The dramatist’s inclusion of unverified folk tales into his play created a narrative that many blindly followed, diverging from authentic Sabarimala rituals. Additionally, Islamic traditions themselves invalidate the practice of offering prayers at mosques with graves, further questioning the validity of the rituals performed at the Vavar mosque.

Okay this the end twist secular Hindus calling masjid/mosque don't even know that one should not offer prayers to Allah where graves Are present

So whatever is happening in kadapa or varavar mosque is invalidated by Islam itself 😂@Eswarkarthikeya @_Saffron_Girl_ @MAD_MAX863… pic.twitter.com/Af0q8oITUm— D…K (@DarkNghtUvacha) November 19, 2024

Vavar Mosque

The mosque believed to date back about 500 years, initially began as a simple thatched hut, though no records confirm its exact origins. Over time, several renovations have occurred, culminating in the substantial concrete structure completed in 2001.

What Does The Inscription Inside Vavar Mosque Say?

The inscription on the plaque at the mosque states the “Ayat-ul-Kursi” (Verse of the Throne“

“Allah! There is no God but He,

the Living, the Self-subsisting, the Eternal.

No slumber can seize Him, nor sleep.

All things in heaven and earth are His.

Who could intercede in His presence without His permission?

He knows what appears in front of and behind His creatures.

Nor can they encompass any knowledge of Him except what he wills.

His throne extends over the heavens and the earth,

and He feels no fatigue in guarding and preserving them, for He is the Highest and Most Exalted.

Allah, the Most High, speaks the truth.”

At the Vavar mosque, it’s written: “There is no god but Allah.” Then why do those who worship Ayyappa go there?

Why do devotees of Allah take the offerings from Ayyappa devotees without hesitation?

This belief in Vavar Swamy is merely a reflection of a general psychology common… pic.twitter.com/7dPSXEmeww

— Pratheesh Viswanath (@pratheesh_Hind) November 12, 2024

The presence of the inscription “There is no god but Allah” at the Vavar mosque raises questions about the nature of Ayyappa devotees’ offerings at this site. This inscription underlines a seeming incongruity: Hindu devotees, revering Lord Ayyappa, traditionally stop to pray and give offerings at a mosque that proclaims an Islamic creed—a belief system not acknowledging Ayyappa or Vavar as divine but God/Allah as the “Most High“.

Offerings are often collected by the Devaswom Board, which manages temple finances across Kerala, but a significant portion of donations made by Ayyappa pilgrims ultimately supports a religious site with no established connection to Lord Ayyapa’s history.

For today’s devotees, this historical understanding presents an opportunity to reconnect with the original spiritual journey to Sabarimala. The path to Lord Ayyappa’s darshan need not include practices added centuries after His manifestation by uninformed people. True devotion is best expressed through adherence to the authentic traditions that have survived since ancient times, untouched by recent political and social constructs.

The growing awareness of these historical facts suggests that pilgrims might reconsider including the Vavar mosque visit in their sacred journey. After all, the Sabarimala pilgrimage’s essential spirituality lies in its ancient, verified traditions—not in its modern additions.

Subscribe to our Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram channels and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.