For I am the one who gave you life,

and the demon who took it away.

O sweet child who fled in fear,

please come back!

Please come back, my treasure!

I shall tear open my withered breast and give it for you!

As blood, as a kiss, come back to me whole.

Come back, resounding loudly.

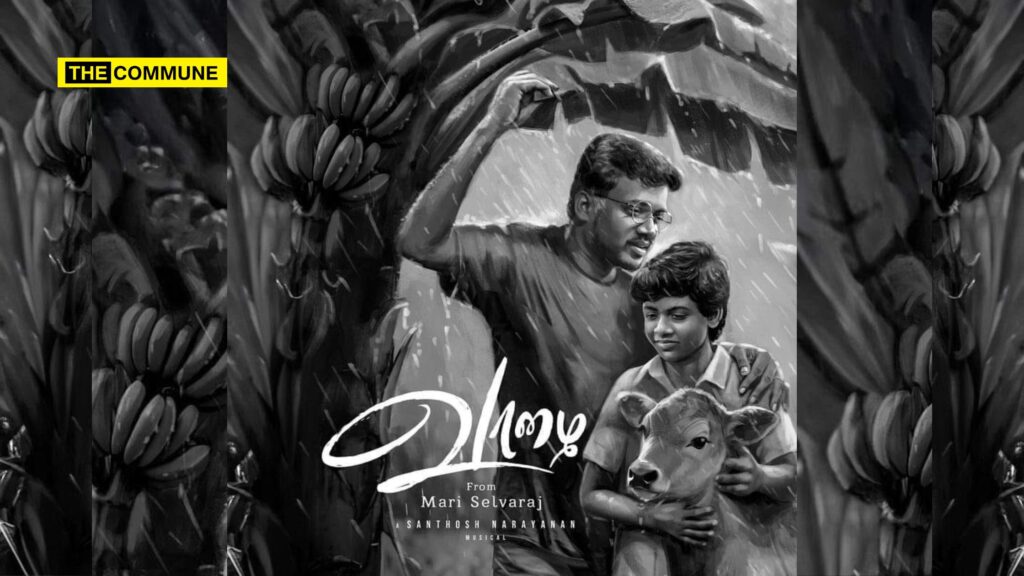

As the end credits roll to this heart-wrenching song, “Padhavathi,” masterfully composed by Santhosh Narayanan, the camera lingers on the protagonist’s mother. In that moment, you can’t help but think about the emotional turmoil Mari Selvaraj’s own mother must have endured in real life.

“No mother should ever face such a tragedy.“, I thought to myself.

Vaazhai is based on a true story and a slice of Mari Selvaraj’s early childhood. Through the eyes of a young boy named Sivanaindhan (a brilliant Ponvel who deserves a national award), Selvaraj takes us on a deeply personal journey, sharing his early experiences and giving us a window into his thoughts and memories. He spends his days engaging in typical childhood play with his best friend Sekar, bickering over Kamal and Rajini.

On weekends, however, his life shifts to the livelihood his entire village is dependent on: lugging bananas from the fields and loading them on to trucks bound for the market. The burden of carrying heavy loads on his head proves to be physically demanding and is superbly portrayed through the song “Oru Oorula Raja”.

While kids usually of his age long for weekends and long holidays after an exam, Sivanaindhan dreads them. His only solace in life is Poonkodi, the social science teacher at his school for whom he develops a liking. These portions come across as harmless and light-hearted. The complex platonic relationship is handled with dignity without making it sexual. Mari lays bare the hardships faced by students from disadvantaged communities with nuance, never forcing it on the audience. You don’t have a villainy teacher from a dominant caste who despises the very presence of kids like Sivanaindhan and Sekar. Had it been a Pa. Ranjith or TJ Gnanavel film, they would’ve forcefully inserted an exaggerated scene with a dominant caste teacher peeling the skin of Sivanaindhan to trigger audience reaction. But Mari is different. There are no deliberate caste-markings shown to identify a particular caste. The caste-based discrimination that happens are shown more realistically and without evoking feelings of hatred among viewers.

Despite demonstrating academic potential, Sivanaidhan struggles to avoid his work obligations, as his strict mother insists he assists in the fields. That’s because following the tragic loss of his father, a dedicated communist, years ago, Sivanaidhan’s mother must manage the household and care for him and his elder sister, Vembu. Mari beautifully puts the viewer in a moral conflict – should we take the side of Sivanaindhan who wants to relieve himself from the lugging burden or his mother who wants to do away with the debt burden that will keep her family in perennial poverty?

Mari is known for making nondescript animals an important character in his films which pivots the storyline. It was Karuppi the dog in Pariyerum Perumal, the donkey in Karnan and a cow in Vaazhai. A critical moment occurs when Sivanaindhan carelessly allows his cow to stray onto a private banana plantation of the middleman who confronts Sivanaidhan’s mother, demanding reparations. In a moment of humiliation before the villagers, she takes off her only pair of earrings and gives them to him.

The guilt of disappointing his mother weighs heavily on Sivanaidhan. Consumed by emotion, he promises to not skip lugging the plantains. After the intermission, he resolves to continue enduring his challenging existence. Nevertheless, an invitation to his school’s annual function, which entails weekend practices, tempts him to revert to his mischievous ways. Aware that his mother will not tolerate any disobedience, he confides in his sister and a local activist named Kani. He sneaks off to school, relishing a joyful dance rehearsal before returning to the fields to join the other workers. The dance rehearsal in empty stomach makes him tired.

Desperate and hungry, he plucks a banana from a plantain plantation of a dominant caste member who reprimands him. Frightened, he races home, only to be met with his mother’s anger, who hurls a bucket at him. He escapes to the river, where he collapses from sheer exhaustion. When he awakens, he is shocked to find the entire village gathered outside, surrounded by police officers and medical staff.

What he sees is utterly devastating. The bodies of his friend Sekar, the rebel Kani, and his sister are displayed for the community, alongside others who tragically lost their lives when an overloaded truck tipped over on the way back from work. A clap of thunder signals a flashback in black and white, revealing the unscrupulous trader instructing the labourers to board the doomed truck, fully aware of its dangerous capacity.

As Sivanaidhan wanders through the village, he silently takes in the sight of the displayed bodies, while villagers express their grief, wailing and beating their chests in mourning.

There is a scene where a famished Sivanaindhan puts his hand into the aluminium pot, takes out the Pazhaya Soru (fermented rice), and eats it as he weeps amidst the gloom that has struck his village and his near and dear ones. The staging of the scene and his mother’s emotional outburst after she sees her son running without even satiating his hungry stomach just puts a lump in your throat.

The film beautifully portrays the life of the Devendra Kula Vellalar community, showcasing their everyday struggles and the strength they find in each other. Mari transports you to his world. You can feel the swampy fields, the centipede running over your face, the smell of Marudhaani (henna) and the taste of the Pazhaya Soru. When Sivanaindhan lugs the plantain load on his head across the fields, it actually weighs on you heavy. When his mother is ill and is unable to go for lugging plantains, you immediately feel the burden.

Mari Selvaraj brings out his best when he remains rooted to the story and the underlying issue. Barring Maamannan and Karnan, he doesn’t resort to unnecessary virtue-signaling and forced messaging through imagery or dialogues. He doesn’t violently impose his ideology by provoking the audience. He remains committed to exposing the black spots in the society by showing things as they are. Yes, he comes from an ideological/political standpoint but one has to empathize and understand where he is coming from. When you are made to do the back and neck breaking work of lugging banana bunches through swampy slippery rice fields for a paltry ₹1 per bunch and you’ve to protest to raise it to ₹2 per bunch, it is but natural for you to speak communism to protest against the exploitation.

There are times when a movie shakes your soul and hits you hard where its hangover lingers on for a few days. Mari did it twice for me with his Pariyerum Perumal and now Vaazhai. Mari Selvaraj’s social and emotional burden weighs heavy on you after watching Vaazhai.

Mari Selvaraj is a gifted filmmaker and he should continue to make films like Vaazhai that will bring out the struggles of his community.

Kaushik is a political writer.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.