The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has long operated beyond its official mandate of humanitarian aid, frequently being linked to covert operations aimed at influencing foreign governments. Established in the early 1960s, USAID was ostensibly created to manage U.S. development assistance programs. However, behind this humanitarian facade, the agency has been accused of funding clandestine activities, facilitating regime change, and undermining sovereign nations.

Following Donald Trump’s inauguration as President, he appointed billionaire Elon Musk to lead the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) to streamline federal spending. Musk ultimately dismantled USAID, calling it a “criminal enterprise.” Since then, increased scrutiny has exposed how USAID and the U.S. State Department have historically engaged in destabilization efforts worldwide. As investigations continue, one of the most telling examples of these covert operations is the forgotten war in Laos, which reveals the deep state’s long-standing involvement in secretive military interventions and illicit activities.

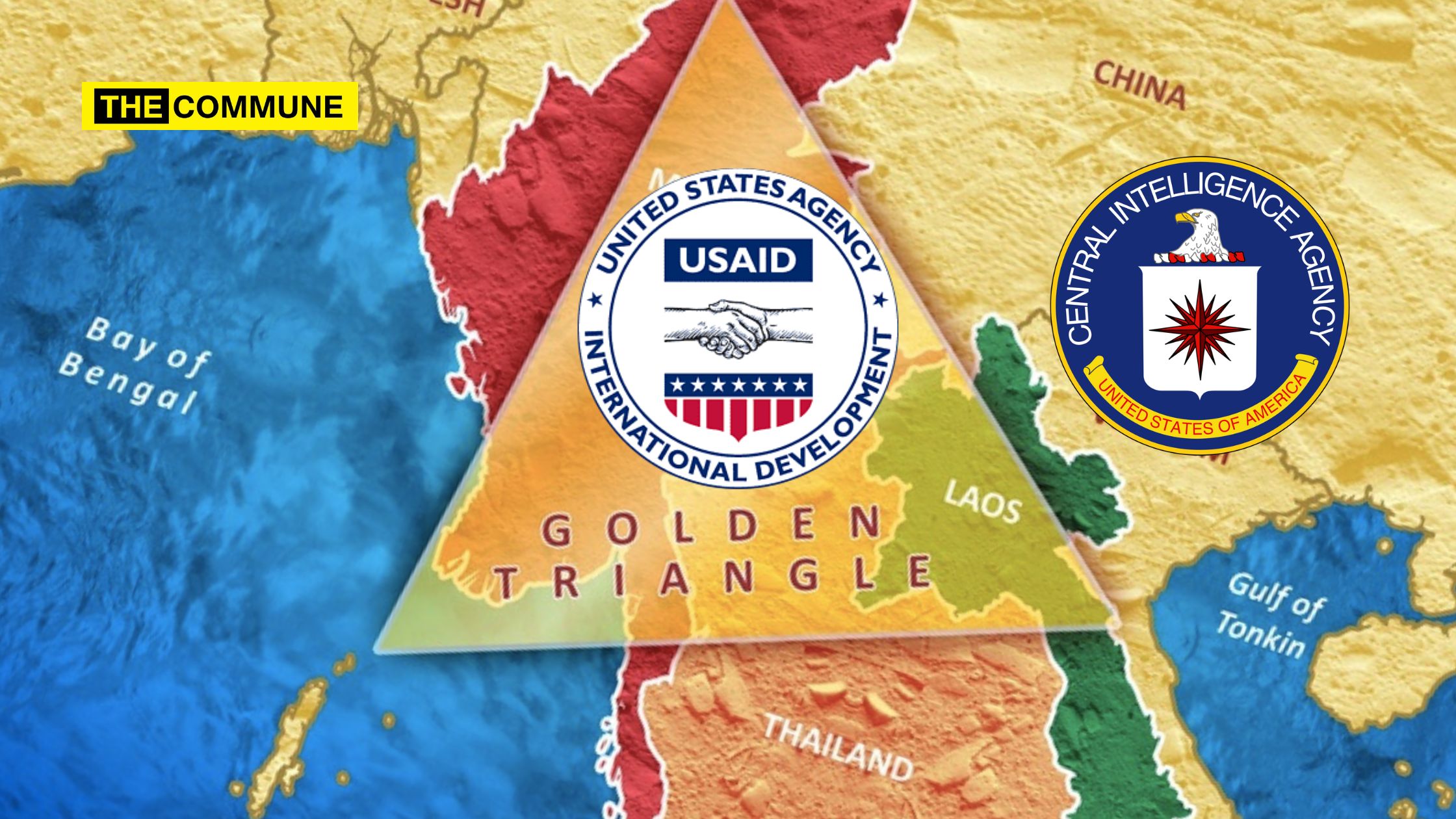

The Covert War in Laos and the Birth of the Golden Triangle

During the height of the Cold War, the United States waged a covert war in Laos from 1964 to 1973 as part of its broader fight against communism. The conflict saw the Royal Laotian forces, CIA-trained guerrilla fighters, U.S.-funded Thai mercenaries, and American military personnel engaging in combat against North Vietnamese forces and the Pathet Lao, a communist insurgent group.

A critical element of this war was Operation Barrel Roll, an extensive aerial bombardment campaign. U.S. Air Force and Navy bombers dropped an estimated 260 million bombs on Laos—an equivalent of 100 bombs per resident. Since Laos was officially neutral in the Vietnam conflict, this military action was conducted in secrecy, violating the Geneva Conventions.

Although USAID was a civilian agency responsible for development aid, it played a far more sinister role in Laos, using humanitarian assistance as a cover to finance covert operations and guerrilla warfare in remote regions.

The Hmong (Meo) Insurgents: A CIA Proxy Army

The Hmong (Meo) people, an ethnic group originating from southern China, Thailand, and Laos, became key players in the U.S. covert war in Laos. Historically marginalized, the Hmong had little integration with the majority Buddhist Lao population, making them ideal recruits for a CIA-backed militia.

The U.S. had been involved in Vietnam for decades, countering communist influence, which had also spread into Laos. As the Royal Laotian Army struggled to combat North Vietnamese incursions and the Pathet Lao insurgency, the CIA saw an opportunity to exploit the Hmong people’s isolation and vulnerability.

Nearly 60% of Hmong adult males were enlisted into CIA-backed guerrilla forces. Declassified reports from the RAND Corporation (1972) describe how USAID funds, supposedly earmarked for refugee relief, were instead used to provide food security for the families of Hmong fighters—effectively serving as financial incentives for enlistment. USAID funds were also funneled into the construction of remote airstrips near the North Vietnamese border, further aiding covert military operations.

The Opium Trade and the Formation of the Golden Triangle

The opium trade had long been a tool of imperial control. During the 19th century, British and American traders flooded China with opium sourced from India, leading to the infamous Opium Wars. However, after India gained independence and Mao Zedong’s government cracked down on opium trafficking in China, the industry relocated to ungoverned regions in Southeast Asia, particularly the Laotian highlands, northern Thailand, and Burma (Myanmar).

The Hmong people had longstanding trade connections with Chinese smugglers and became key players in the cultivation of poppy for the opium trade. Triads and other criminal networks facilitated this illicit business, while CIA-backed warlords in Laos, such as General Vang Pao and General Ouane Rattikone, took control of drug production and trafficking.

With CIA assistance, opium was airlifted from remote Laotian airstrips—built with USAID funds—to processing centers in Saigon. From there, it was sold to U.S. troops stationed in Vietnam. By the late 1960s, nearly 10% of American servicemen in Vietnam were addicted to heroin, fueling a crisis back home.

CIA’s Involvement in Drug Trafficking

Colonial and royal regimes had historically leveraged the opium trade for financial gain, but during the Vietnam War, the CIA actively facilitated its expansion. Originally, the agency backed Kuomintang (KMT) forces who had fled to Burma after losing the Chinese Civil War. The KMT, rather than fighting to reclaim China, instead took control of opium production in the Shan hills and smuggled it into Thailand, further embedding drug trafficking into the region’s economy.

In Thailand, General Phao Sriyanonda, head of the Thai National Police, was propped up by the CIA and provided with military resources ostensibly to combat communism. However, he used these assets to turn Bangkok into a hub for global heroin distribution.

In Laos, CIA-linked groups transported opium via Air America, a covert airline used for U.S. operations in Southeast Asia. Reports surfaced that heroin laboratories were operating under the protection of Laotian military generals, with drugs being distributed to American troops and trafficked globally.

The War on Drugs and the Aftermath

By 1971, as heroin addiction among U.S. troops reached alarming levels, President Richard Nixon launched the War on Drugs, focusing on identifying and disrupting supply routes. The RAND Corporation’s assessment, though praising the effectiveness of tribal guerrilla forces, acknowledged that USAID funding for these programs was being scaled back by 1968.

With Nixon’s diplomatic outreach to China in 1972, Laos lost its strategic importance in the Cold War. After the U.S. withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975, American interest in Laos waned further. Because the U.S. intervention in Laos had always been classified, the conflict became a forgotten war in mainstream historical narratives.

However, the tactics developed in Laos—such as CIA-backed militias, funding insurgencies through drug profits, and using USAID as a financial cover—were later replicated in Colombia during the 1980s and Afghanistan in the 2000s.

Many former Hmong fighters were eventually resettled in the U.S. as refugees. Meanwhile, the Golden Triangle remains a global center for drug production, plagued by ethnic conflicts and controlled by criminal warlords.

(With Inputs From OpIndia)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.