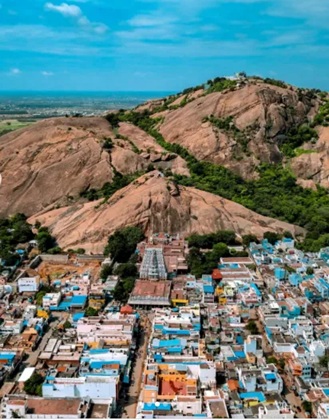

Thirupparankundram is one of the oldest temples of Tamilakam and the first among Murugan’s six abodes. Though revered in tradition, it did not enjoy the same prominence as some of the other Murugan shrines until recent decades—let alone the many legal disputes it has faced over the past century.

History

The hill, always honoured as Thiru-Parankundram, appears in early Sangam literature. Agananooru 59 by Madurai Marudhan Ilanaganar speaks of Murugan who vanquished Surapadman and resides on this cool, cave-filled hill. Agananooru 149 mentions a Murugan temple here, noting that after defeating the Cheras, Pandya king Chezhiyan returned to Madurai where the temple’s peacock flag flew high amid continuous festivals.

Paripadal has eight hymns on Murugan, several exalting Thirupparankundram as equal in sanctity to the Himalayas. One verse describes a painted hall in the temple depicting scenes such as Indra deceiving Ahalya in the form of a cat, with guides explaining the stories to visitors. Nakkeerar’s Thirumurugatrupadai—sung at Thirupparankundram—celebrates it as the foremost among Murugan shrines and offers a vivid portrayal of the sacred hill. In fact, the hill itself is regarded as a Shiva Linga, which is why a Giri Prakara has been established for devotees to circumambulate the entire hill

The temple saw significant development during the medieval Pandya period. In the early 8th century, under Pandya Parantaka Nedunjadaiyan, a rock-cut temple was excavated with five shrines dedicated to Ganapathi, Murugan, Shiva, Durga, and Vishnu. A similar Pandya cave temple from this period exists at Trichy (Lower Cave).

Two inscriptions from this era survive at Thirupparankundram. One, found in the garbhagriha of the present shrine, records: “In the 6th regnal year of Ko Maran Sadayan, Sattan Ganapathi, the Mahasamandan (commander) of the king, renovated the temple and the sacred tank Sri Tadakam,” the latter identified with the present Lakshmi Theertham.

The temple attained its present extensive structural form during the Nayaka period, especially under Thirumalai Nayakar. All these clearly establishes the fact that the Murugan temple in the hill is in worship for more than two thousand years.

Topography of the Hill

To understand the background of the legal issues surrounding the hill, it is important to know its physical and sacred layout. Thirupparankundram hill consists of two sections with two distinct peaks. The northern side of the hill houses the famous Murugan temple on the lower part of the hill. On the southern side stands an early Pandya-period rock-cut shrine known as the Umai Andavar (Ardhanareeswara) temple.

On the south-western slope, a flight of steps leads to Jain beds with Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions dating to the pre-Common Era. The north-western side has two bas-relief sculptures of Jain Tirthankaras accompanied by a Vattezhuthu inscription. Adjacent to these shrines is the temple of Palani Andavar. From this zone, steps continue upward toward the summit.

A dargah dedicated to Sikandar Shah is there atop the hill, with multiple narratives explaining its origin. Regardless of its beginnings, worship at the dargah began a few centuries ago and continues today. Beyond the dargah lies the Kasi Viswanathar temple with a pond in front. At the very top is a flat plateau between the two hill sections, traditionally known as Nellithoppu.

Legal battles

Despite the temple and hill having an antiquity of over 2,000 years, Thirupparankundram has been entangled in one legal dispute or another for more than a century. The Olugu accounts of 1802 record that the British Government recognised the hill as the property of the deity. As early as 1879, the British administration attempted to quarry the hill, which was strongly opposed by the temple authorities.

In 1915, the Dargah began occupying the Nellithoppu area by constructing a few structures. After prolonged disputes, the matter reached the court in 1920 (O.S. No. 4 of 1920). The Devasthanam, as plaintiff, argued that the entire hill belonged to the temple and that no construction was permissible. The Dargah representatives contended that the hill had two distinct parts, and that the upper portion—referred to by them as Sikandar Malai—belonged to them, thereby claiming ownership of Nellithoppu as well. Meanwhile, the Government also joined the case, arguing that the hill was state property.

After considering all sides, the Madurai Court delivered its judgement—an elaborate order that traces the hill’s history before arriving at its conclusions. The court referred to a 1909 Government Order stating that the entire hill was worshipped by Hindus as a Shiva Linga, and that the temple was not a separate structure but carved directly into the rock. It also noted an 1863 British notification referring to the “Thirupparankundram Subramanya Swami temple and its four sides including the Malai Prakaram.”

The judge personally inspected the hill before delivering the final verdict. The court ruled that the entire hill belonged to the temple, except the Dargah along with its compound wall and flagstaff, the Nellithoppu area, and the steps leading to the Dargah.

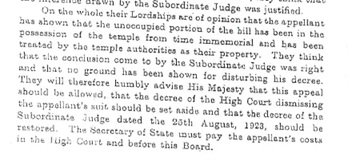

The Dargah representatives did not accept the Madurai court’s order and appealed to the Madras High Court in 1923. Although the Government was initially reluctant to participate, the High Court added it as a party and eventually ruled that the hill belonged to the Government. The Temple Devasthanam then approached the Privy Council. After examining the details, the Privy Council in 1931 upheld the Madurai court’s judgement, granting ownership of the entire hill to the Thirupparankundram temple, except for the three areas previously specified. It also observed that the construction of the Dargah was an “infliction which the Hindus might well have been forced to put up with.”

This status continued until the 1950s. Meanwhile, the Thirupparankundram Devasthanam had come under the administration of the Madurai Meenakshi Temple Devasthanam. In 1958, the Dargah side attempted to cut rocks on the hill to construct additional structures. The Madurai Devasthanam strongly objected and filed a case (O.S. No. 111 of 1958). The Dargah argued that since the rocks were located near Nellithoppu, that area belonged to them, giving them the right to quarry. The temple authorities firmly opposed this claim.

This status continued until the 1950s. Meanwhile, the Thirupparankundram Devasthanam had come under the administration of the Madurai Meenakshi Temple Devasthanam. In 1958, the Dargah side attempted to cut rocks on the hill to construct additional structures. The Madurai Devasthanam strongly objected and filed a case (O.S. No. 111 of 1958). The Dargah argued that since the rocks were located near Nellithoppu, that area belonged to them, giving them the right to quarry. The temple authorities firmly opposed this claim.

The court ordered a detailed survey to demarcate boundaries. Based on the findings, it issued a decree restraining the Dargah from cutting stones anywhere outside the flat expanse of Nellithoppu.

Lighting of Karthigai Deepam

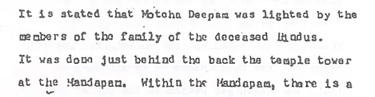

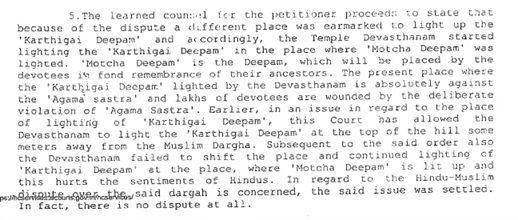

During these developments right from British period, locals say that the Karthigai Deepam—traditionally lit at the summit of the hill—was shifted to a Deepam Mandapam at the Uchipillayar temple located on a smaller hillock behind the Murugan temple. This structure was originally used by residents to light the Moksha Deepam.

In 1994, Hindu Munnani demanded the restoration of lighting the Karthigai Deepam at the summit of the hill. Shri Rajagopalan, the state president who led the agitation, was assassinated that same year. The organisation requested the temple Devasthanam to light the Deepam atop the hill so that the surrounding households could follow the traditional practice. The matter went to court, where HRCE argued that the lamp would continue to be lit only at the “traditional place.” The litigation continued for a couple of years. During this period, the Karthigai Deepam was shifted to the top of the Deepa Mandapam, where a copper vessel was used for lighting the lamp.

In 1994, Hindu Munnani demanded the restoration of lighting the Karthigai Deepam at the summit of the hill. Shri Rajagopalan, the state president who led the agitation, was assassinated that same year. The organisation requested the temple Devasthanam to light the Deepam atop the hill so that the surrounding households could follow the traditional practice. The matter went to court, where HRCE argued that the lamp would continue to be lit only at the “traditional place.” The litigation continued for a couple of years. During this period, the Karthigai Deepam was shifted to the top of the Deepa Mandapam, where a copper vessel was used for lighting the lamp.

In 1996, the court ruled that since the Karthigai Deepam festival was approaching, the temple management could light the Deepam at the Uchipillayar temple for that year alone. From the following year, the Devasthanam could choose any other suitable location.

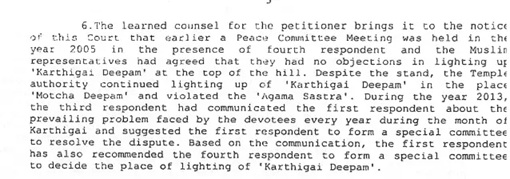

In 2005, a peace meeting was organised between the Hindu Baktha Jana Sabha of Thirupparankundram and the Dargah authorities. Both sides agreed that the Deepam could be lit at any spot located at least 15 metres away from the Dargah compound. Despite this, the temple administration continued to light the lamp at the Uchipillayar temple.

The issue resurfaced in 2014 when a writ petition was filed seeking to restore the lighting of the Deepam at the hilltop. The petitioner argued that the current location was meant only for the Moksha Deepam, not the Karthigai Deepam, and that the deviation hurt the sentiments of Hindus.

It was also pointed out that the 2005 peace agreement had not been implemented. HRCE opposed the petition. The court eventually dismissed the case. The petitioner appealed, but the appeal too was dismissed on the ground that the requested location was too close to the Dargah.

In 2024, an attempt to perform animal sacrifice at the Dargah was opposed by Hindu organisations, leading to another round of litigation. The case was heard by a Division Bench of the Madras High Court (Madurai Bench), which delivered a split verdict—one judge ordered a ban on animal slaughter on the hill, while the other dismissed the petition. As a result, the matter was referred to a third judge, who upheld the ban and confirmed that animal slaughter on the hill is prohibited.

In 2024, an attempt to perform animal sacrifice at the Dargah was opposed by Hindu organisations, leading to another round of litigation. The case was heard by a Division Bench of the Madras High Court (Madurai Bench), which delivered a split verdict—one judge ordered a ban on animal slaughter on the hill, while the other dismissed the petition. As a result, the matter was referred to a third judge, who upheld the ban and confirmed that animal slaughter on the hill is prohibited.

In 2025, Thiru Rama Ravikumar and a few others filed a petition before the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court seeking a direction to the temple authorities to light the Karthigai Deepam at the Deepathoon. HRCE opposed the plea. After evaluating the submissions, the learned judge ruled in favour of lighting the lamp at the Deepathoon and personally visited the hill to inspect the location.

In his judgement, the judge made several key observations:

1. The petitioners are persons of interest, as the demand for lighting the lamp at the Deepathoon was made by Hindu worshippers of Lord Murugan.

2. There is no merit in directing the petitioners to file a civil suit, since the question of property rights over the hill was conclusively settled as early as 1923.

3. The respondents’ claim that the matter was already decided in the 2014 judgement is untenable. The 2014 petitioner sought permission to light the lamp at the hilltop, which falls within the Dargah’s property. In contrast, the 2025 petition specifically concerns the Deepathoon—located on the lower peak—which belongs to the temple.

4. Lighting a lamp atop a temple is an ancient Tamil tradition.

The Tamil epic Jivaka Chintamani refers to “Kundril Karthigai Vilakkittanna,” indicating the age-old custom of lighting lamps on hilltops.

5. Protection of temple property is also a legal obligation.

The judge cited the practice of closing all doors of the Madras High Court once a year to prevent easement claims by the public. Similarly, temple authorities must remain vigilant to prevent encroachments. Lighting the lamp at the Deepathoon is therefore necessary not only to honour religious tradition but also to safeguard the temple’s property.

The learned judge also referred to the animal-slaughter case and noted that it was activists who took initiative, while the temple trustees had remained silent. He further cited the minutes of the peace committee meeting held on 1 December 2005, during which the Dargah management signed an agreement stating that they had no objection to lighting the Karthigai Deepam at the Deepathoon. They expressly agreed that the lamp could be lit at any location situated at least 15 metres away from the Dargah.

What followed after this verdict is now well known. Appeals have been filed, and the Hindu community is awaiting the next judgement.

TS Krishnan is a Tamil scholar, historian and author of the book The Cholas.

This article was originally published here and has been republished in The Commune with permission.

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.