The Print’s recent long-form piece on communal violence in Sambhal is a masterclass in biased journalism, riddled with omissions, half-truths, and a clear agenda to distort historical facts. While ostensibly presenting an in-depth report on the region’s communal tensions, The Print achieves little more than peddling a narrative that paints one community as a perpetual victim while conveniently burying or downplaying documented atrocities against others. Here’s why this report is not just flawed but dangerous.

Downplaying The 1978 Pogrom Against Hindus

The Print’s treatment of the 1978 pogrom is its most glaring flaw. Historical records and parliamentary debates clearly document the horrific scale of violence against the Hindu community during this period. Hindu shopkeepers and residents were targeted, temples were desecrated, and curfews crippled the town. Yet, The Print glosses over these atrocities, treating them as mere footnotes while focusing disproportionately on speculative or anecdotal grievances from the other side. Hindus have been a minority in the region for a very long time. To accuse Hindus of orchestrating such communal acts when their numbers are far less than the majority community in that area is hypocrisy.

Multiple accounts confirm the Hindu community’s claim that they were worshipping at the disputed site before being forced to stop by a brutal campaign of intimidation and violence. By barely mentioning this critical fact, the report attempts to rewrite history, erasing the suffering and resilience of an entire community.

The Print goes to extraordinary lengths to portray Muslims as the sole victims in Sambhal’s communal history. While the report cites anecdotal memories of fear and victimhood among Muslim residents, it systematically ignores the overwhelming documented data that shows Hindus bore the brunt of violence over decades. Local administration records from 1939 to 1978 reveal that the Hindu community suffered hundreds of deaths and desecrations of their places of worship.

Sambhal has a long, violent history of anti-Hindu aggression, as I have documented in the thread below

In 1978, 23 Hindus were killed in a pogrom – 14 of them burnt alive in a mill. The Nov 24 incident was not unprecedented

The only difference this time was that security… https://t.co/fZzrPfJtnl

— Swati Goel Sharma (@swati_gs) December 2, 2024

Yet, The Print relegates these facts to the background, choosing instead to focus on vague allegations and unsubstantiated claims.

Here is an account of what happened in Sambhal in 1978 from the horse’s mouth – the Hindu victims’ families’ mouth.

Sambhal has a long and violent history of anti-Hindu aggression, exemplified by a brutal pogrom in 1978 that claimed the lives of 23 Hindus, 14 of whom were burned alive in a mill. The 24 November 2024 incident was not unprecedented; the difference this time was that the aggression targeted security forces rather than the minority Hindu community.

The 1978 massacre, which occurred near Sambhal’s disputed mosque, was triggered by rumors of a Hindu killing an imam and a sadhu performing puja there. Journalist Swati Goel Sharma documented the incident, speaking to the family of Banwari Lal Goel, the mill owner and a respected figure in Sambhal who served as the local president of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP). Banwari Lal was known for his fairness, often mediating disputes for Muslim families.

On 29 March 1978, when violence erupted following provocations by Muslim League leader Manzar Shafi’s followers, Banwari Lal and his workers sought refuge in his mill compound, a large ahaata spread over four beegha in Nakhasa Bazaar. Tragically, the rioters targeted the mill two hours after the violence began, using a tractor to repeatedly ram the front wall until it collapsed, and then throwing burning tires inside while blocking any escape.

Official records state that of the 25 people killed in Sambhal that day, 23 were Hindus, with 14 perishing in the mill. Banwari Lal’s sons, Navneet and Vineet later found only ashes and part of their father’s glasses in the smoldering ruins. A sole survivor, Hardwari Lal, who hid inside a drum, provided crucial testimony that confirmed the horrific details and identified the victims. The massacre devastated the Goel family, leaving them in penury. Banwari Lal’s sons rebuilt their lives from scratch and eventually relocated to Delhi in 1993, turning to peppermint production after selling most of the mill compound in Sambhal. A portion of the property, however, remains under their ownership and has hosted major Hindu religious events, including the Ram-Bharat Milaap episode of the annual Ramlila. Vineet Goel recounts that some local Muslims quietly revealed the names of the perpetrators after the massacre, and the family discovered that the attackers included Banwari Lal’s business associates. This betrayal led the Goels to sever all business ties with the other community. Like many Hindus in Sambhal, Vineet blames the then-District Magistrate Farhat Ali for siding with the rioters and failing to protect the Hindu community. Historical records of the massacre are sparse, with no global media coverage or recent news on a trial. A book titled Mob Violence in India by SLM Prachand, briefly mention the episode, but the family recalls no court trial ever taking place.

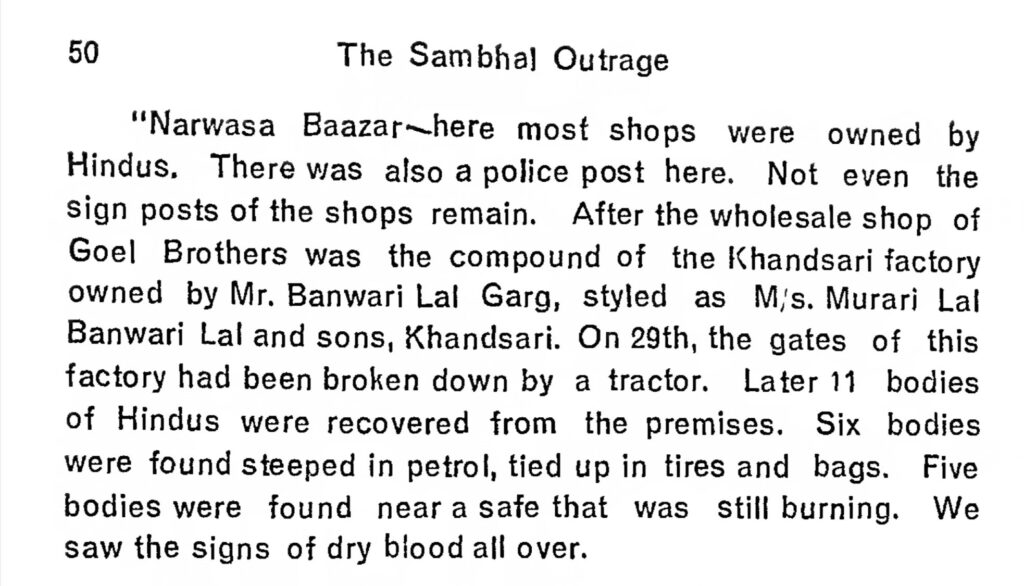

A paragraph in the book reads “Narwasa Baazar here most shops were owned by Hindus. There was also a police post here. Not even the sign posts of the shops remain. After the wholesale shop of Goel Brothers was the compound of the Khandsari factory owned by Mr. Banwari Lal Garg, styled as M/s. Murari Lal Banwari Lal and sons, Khandsari. On 29th, the gates of this factory had been broken down by a tractor. Later 11 bodies of Hindus were recovered from the premises. Six bodies were found steeped in petrol, tied up in tires and bags. Five bodies were found near a safe that was still burning. We saw the signs of dry blood all over.”

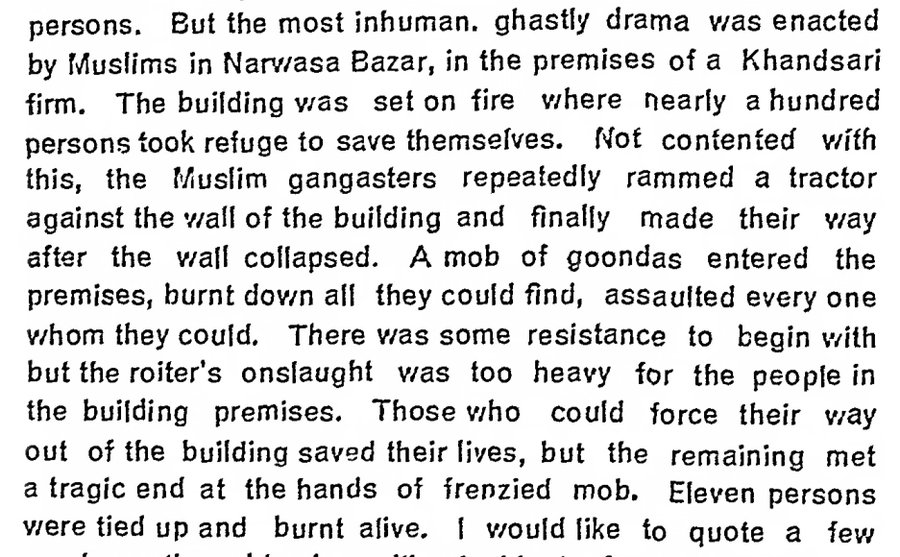

Another paragraph reads, “But the most inhuman. ghastly drama was enacted by Muslims in Narwasa Bazar, in the premises of a Khandsari firm. The building was set on fire where nearly a hundred persons took refuge to save themselves. Not contented with this, the Muslim gangasters repeatedly rammed a tractor against the wall of the building and finally made their way after the wall collapsed. A mob of goondas entered the premises, burnt down all they could find, assaulted every one whom they could. There was some resistance to begin with but the roiter’s onslaught was too heavy for the people in the building premises. Those who could force their way out of the building saved their lives, but the remaining met a tragic end at the hands of frenzied mob. Eleven persons were tied up and burnt alive.”

This lack of justice underscores the enduring trauma and loss the Goel family and the Hindu community of Sambhal have endured.

The Print mentions that “even though several textual records, including parliamentary records and books like SLM Premchand’s 1979 publication Mob Violence in India say that it was a Hindu who killed the maulana. The maulana’s family moved to Ahiraula in UP’s Azamgarh shortly after — which several older Muslim residents remember. “

Despite there being records and books documenting the truth, The Print refuses to acknowledge it and paints its version of the truth. They took only what was suitable for their propaganda and discarded the above truths mentioned in the same book they refer to in their “research piece.”

14 Hindus were burnt alive in a mill very near to Sambhal’s disputed mosque in 1978

Rumours of a Hindu killing an imam and a sadhu performing puja there triggered this massacre

I spoke to the family of the mill owner, who was also killed

A thread on this forgotten tragedy 🧵 pic.twitter.com/JgdpcHFL5R

— Swati Goel Sharma (@swati_gs) December 1, 2024

The Print’s selective framing of Hindus as perpetrators not only distorts reality but also fuels further divisions by perpetuating a one-sided victimhood narrative that erases the genuine pain and loss experienced by Hindus in Sambhal.

The piece treats the fears of Sambhal’s Hindu community with dismissive indifference in The Print’s report. Hindu shopkeepers and residents have repeatedly expressed their anxieties about living under constant threat, yet these legitimate concerns are portrayed as peripheral or exaggerated. Token references to these fears are swiftly overshadowed by the narrative of Muslim victimhood. This dismissal is not just insulting but indicative of The Print’s unwillingness to engage with uncomfortable truths that do not align with its agenda.

“Sensitive Zones”

The Print perpetuates the trope of Sambhal as a “sensitive zone,” a term often used to absolve accountability for violence against Hindus. By normalizing this label, the report subtly justifies the targeting of the Hindu community as an inevitable consequence of living in a “communal tinderbox.” Instead of questioning why such a designation exists or examining the systemic failures that allowed violence to persist, The Print leans into the stereotype, further entrenching the narrative of inevitability.

By failing to acknowledge the Hindu community’s longstanding grievances and real victimhood, The Print’s report aligns itself with a broader agenda to erase uncomfortable truths about communal violence in India. This erasure is not accidental; it is a deliberate attempt to craft a narrative that suits a particular ideological lens, one that sees Hindus only as oppressors and never as victims.

The Print’s Sambhal report is not journalism; it is propaganda masquerading as investigative reporting. By selectively highlighting certain narratives while burying others, it does a disservice not only to the truth but also to the cause of communal harmony. True journalism should illuminate all facets of a story, not pick and choose facts to fit a predetermined agenda.

In a time when communal tensions remain a sensitive issue, such biased reporting only serves to deepen divisions and fuel mistrust. The Print’s credibility as a platform for fair and honest journalism remains in question.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.