During the third Anglo-Mysore war in 1792 between the East India Company and Tipu Sultan of Mysore, Cowasjee, a Parsi bullock-cart driver and four other British soldiers were taken prisoner by Sultan at Seringapatam, Karnataka.

In a truly barbaric Islamic way, their noses were cut off before releasing along with their amputated noses as a mark of humiliation. For nearly a year, these soldiers went without a nose until Sir Charles Warre Malet, a British minister in the Peshwa court at Poona, came across an oilcloth merchant with a feeble scar on his nose.

The merchant explained that his nose had been amputated as a punishment for adultery and was later rebuilt by a Poona potter using his forehead skin. The oilcloth merchant could never have predicted that his disclosure would spark a chain of events that would establish the “Hindu method” as the gold standard of nose reconstruction worldwide.

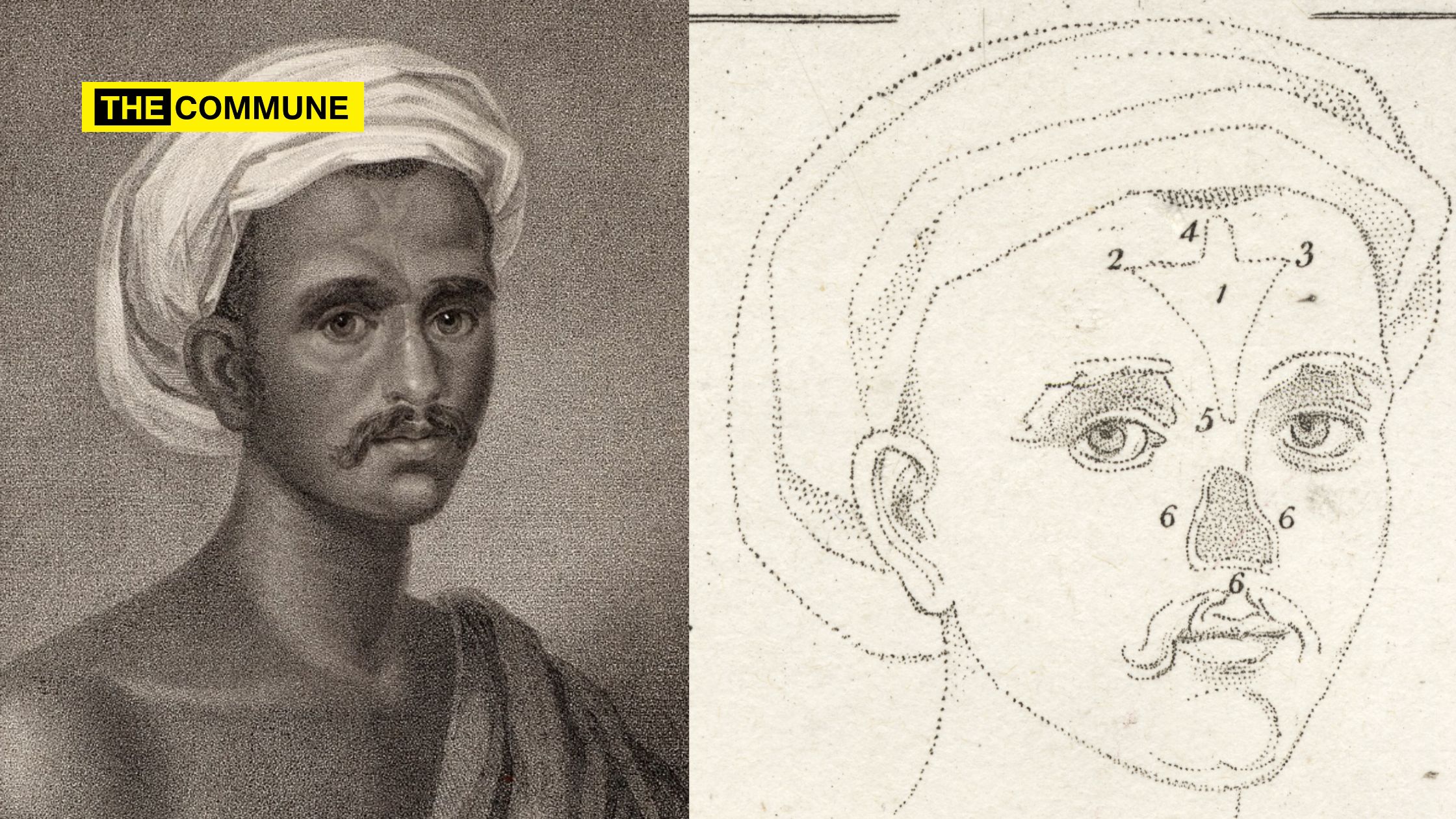

Sir Charles summoned the potter recommended by the oil-cloth merchant to reconstruct the noses of Cowasjee and the other four soldiers. This nasikasadhana art had been practised in complete secrecy and passed down from generation to generation within a single family. Cowasjee’s forehead flap nasal reconstruction, on the other hand, was witnessed by Mr. Tho Cruso and Mr. James Findlay, two British physicians from the Bombay Presidency. After the operation, the patient was required to lie on his back for 5-6 days. On the 10th day, bits of soft cloth were put into the nostrils to keep them sufficiently open. The procedure was always successful, and the new nose almost resembled the natural one. After a while, the scar on the forehead was no longer visible.

Cowasjee’s portrait depicting the successful surgery was painted ten months later, in January 1794, by the British painter James Wales. In March 1794, the copper portrait appeared in Bombay. The news was published in the Madras Gazette on 4 August 1794, and in October 1794, in a letter to the editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine, Sylvanus Urban described “a very curious chirurgical procedure” of “affixing a new nose on a man’s face” that was unknown to civilised Europeans what had been practised for generations in uneducated India.

In January 1795, the surgical procedure was published as “A Singular Operation,” and Cowasjee’s portrait appeared alongside the article. In April 1795, The Courier published an article titled “Account of the method of supplying artificial noses as practised by the natives of the Malabar coast”, claiming supremacy of the Indian method. After a detailed discussion with Lieutenant Colonel Ward (Cowasjee’s commanding officer), J.C. Carpue, a British surgeon, successfully used this method on two patients in 1814 and published his paper in 1816. The procedure became widely popular in Europe as the “Indian Method,” but not the Hindu Method. Despite many modifications since then, the procedure has stood the test of time and is still the best method of nose reconstruction today.

The publication of the nasal reconstruction in The Gentleman’s Magazine and later by Carpue laid the foundations for modern plastic surgery. The “Indian Method” became popular all over the world, kindled the interest of the Western world, and brought recognition to India as the birthplace of plastic surgery.

The first principles of plastic surgery were articulated by Sushruta in his treatise Sushruta Samhita in 600 BCE and translated into Arabic by Ibn Abi Usaibia in the 11th century, travelling far into Arabia, Persia, and Egypt; however, the Western world became aware of it much later. Susruta described over 300 surgical procedures and about 120 surgical instruments (all his own inventions). He also talks about 385 plant-generated, 57 animal-generated and 64 mineral-generated medicine.

Medicines were produced in the form of Powders, distillates, decoctions, mixtures, gels. He talks of 24 kinds of swastiks, 2 kinds of sandas (pliers), 28 types of needles and 20 kinds of catheters. Sushruta gave a description of 14 kinds of bandages besides the six bone dislocations and 12 kinds of fractures of bones. His book also talks about 28 diseases related to the ear and 26 connected to the eyes.

While Cowasjee was immortalised in British publications, paintings, and engravings. the surgeon whose skills gave Cowasjee a nearly normal nose went unnoticed. Through this, the British attempted to prove to the world that they took good care of their soldiers. By concealing the name of the surgeon, they made sure that India did not get its due recognition.

The case is significant because it is one of the few in medical history where the patient is more popular than the surgeon. However, the event still managed to enable the rightful recognition of India as the origin of plastic surgery and the restoration of its honour. Unlike today’s plastic surgery, it was never about superficial cosmetic surgery in ancient India. It was always about treating serious deformities.

Even today, Indian vaccines, like Covishield, continue to save crores of people around the world.

Attached image is of Cowasjee after surgery by James Wells.

Sources

Carpue J C. “An account of two successful operations for restoring a lost nose from the integuments of the forehead in the cases of two officers of His Majesty’s Army. London: Longman, 1816.

(This article was first published here and has been republished with permission.)