Animals and birds take up a significant portion of our Hindu Puranas and Itihasas. Out of all birds and animals, the elephant is one animal that finds repetitive mention. Starting with Lord Ganesha, whom Hindus pray to before starting any endeavour, elephants are found across all our epics and stories. It includes Airavata- the vahana (mode of movement) of Indra; Gajendra- the bhakta (devotee) of Lord Narayana; Ashwathama- the elephant that dies in the Kurukshetra war; so on and so forth.

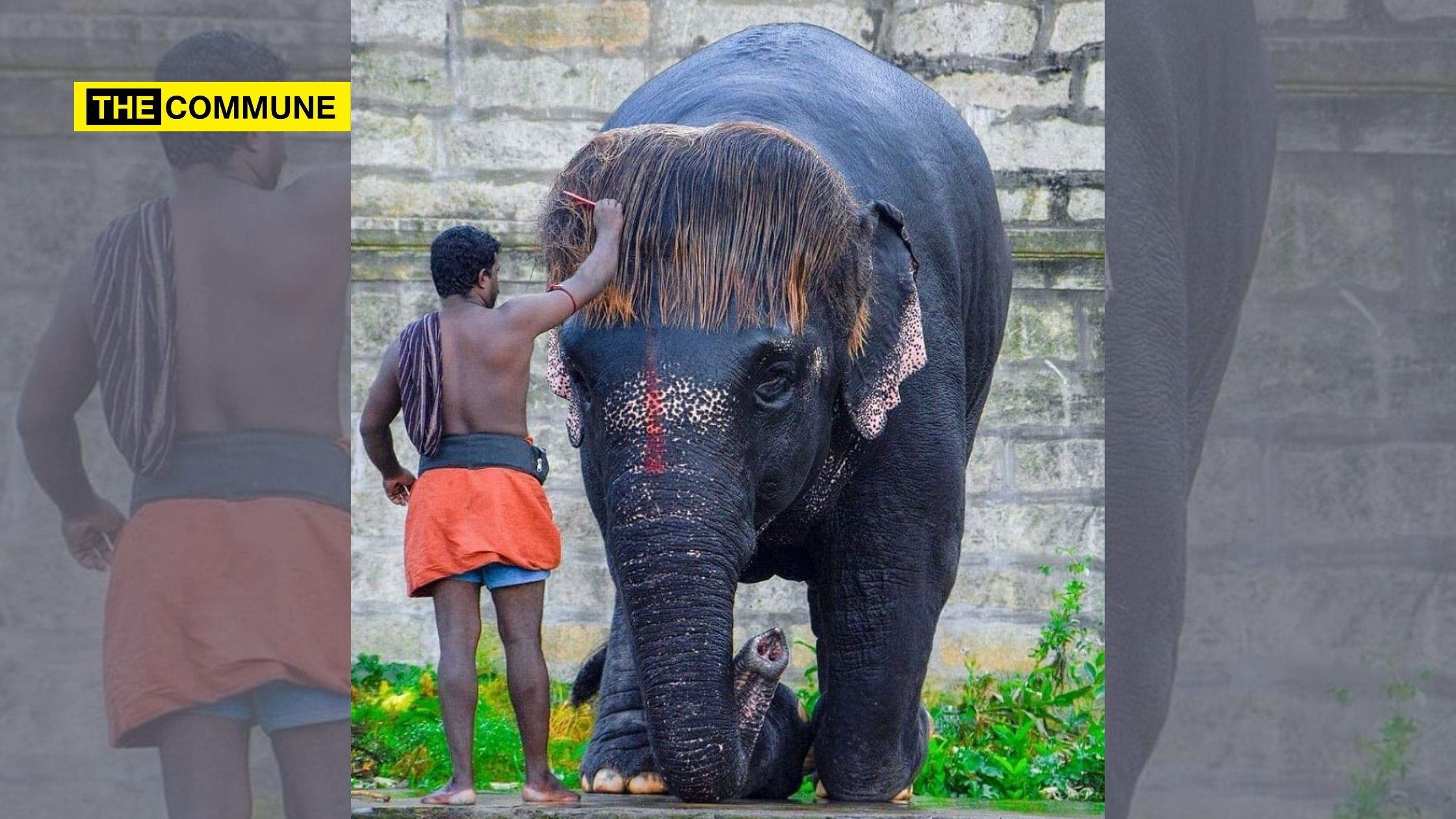

Even in our contemporary world, elephants have an integral part to play in Hinduism. As we see when we enter most big temples, elephants are present, and they play a role in the festivals for the deity. Every temple has a specific space dedicated to the elephant where it is bathed, fed and rested. Ancient temples were built along with a portion of the complex dedicated to elephants. While these are well-known things, there are some other unknown aspects about temple elephants. Why do we have the practice of temple elephants in the first place? Which breed of elephants do temples select? What gender of elephants are preferred by temples predominantly?

Speaking about why we have elephants in temples, Kulithalai Ramalingam, a saivaite religious preacher said, “According to the Agamas, we have elephants for two purposes. Firstly, the agamas say that the water for abhisheka (thirumanjanam) for the deity is to be brought from the river or tank to the temple by placing it on the elephant. Secondly, in bigger temples with 5 Prakaras, the deity is to be brought in circumambulation around the temple on the elephant, during nityotsavam (daily festival). This also extends to when the deity comes out of the temple during festivals.” In essence, the temple elephant is an essential part of the day-to-day activities for the temple deity.

While talking about Bob-cut Sengamalam, the elephant of the Mannargudi Rajagopalaswamy Temple, Rajagopal, the Mahout said, “She came to our temple in the year 2002, when she was 14. Now, she is 34 years old. Before her, we had Senior Sengamalam who lived for 86 years as the temple elephant and passed away due to old age. Junior Sengamalam was donated to our temple by Ms Sasikala’s brother, Mr Dhivakaran.” Rajagopal has been associated with the temple elephant since his birth, but he has taken it up as a profession only after his father passed away in 2018.

In most temples, elephants are donated and not bought. So, the breed and gender of the elephant are not pre-fixed, as the temple cannot demand a specific breed from the person donating. In Mannargudi, the elephants have been females. However, this differs from temple to temple. But generally, mostly only the Indian breed of elephants are taken up for temple service. “Temples prefer female elephants as they’re easier to manage during their musth period than their male counterparts,” Rajagopal mentioned.

Considering the size of an elephant, the food intake of the animal is also beyond imagination. For example, Sengamalam generally takes 5 Kg of Venn Pongal in the morning and night. In the afternoon, she is given 250 Kg of cattle feed including reed, coconut leaves and hay. “Per day cost of the cattle feed is ₹200. This is sponsored and provided by the HR&CE department,” he said.

While mahouts have been taking quite good care of their elephants, many have gone to court against this practice, asking for a complete ban on this tradition of temple elephants. Even recently, the Tamil Nadu forest department constituted a seven-member team of experts to investigate whether temple elephants in the state are being subjected to harassment and whether these elephants are in a position to be held in captivity. The argument placed by these animal activists and the forest department is that the elephants are not taken care of properly, and are subjected to loneliness and torture. Therefore they have been trying to seek a ban on this tradition.

Speaking about the so-called torture of temple elephants, Saraswathi, an animal activist who has been fighting for the preservation of this practice, said, “You would assume that we have elephants in temples because of the Agamas of the temples. Well, while that may be true, the practice of temple elephants was initiated to protect wild elephants from fatality and death. A recent study says that 130 wild elephants died in 15 months in the Western Ghats, due to casualties like electrocution and railway accidents. However, in temples, elephants are taken very good care of, with appropriate feeding and healthcare facilities. It is important to understand that elephants are rather protected through this practice than tortured.”

Many who has asked for a ban on this practice also argued that the elephants are subjected to loneliness, and therefore they should not be separated from their habitat. When Rajagopal was asked about this, he said, “How can Sengamalam ever be lonely when I am always with her? She is like my elder daughter, not just any elephant. If she falls sick, I won’t even feel like eating or sleeping. That is the bonding I have with her. She keeps talking to me, and rightfully asks me whatever she requires, like water, rest or food. So, Sengamalam is never lonely.”

About loneliness, Saraswathi added, “A temple elephant will never feel alone because it will not only be surrounded by the mahout, but also by the devotees of the temple at all times. For the elephant, the Mahout and his assistant are its mother and father. They will have an irreplaceable bonding from a very young age.”

Those who seek a ban on this tradition also site that elephants are mostly tortured when trained. Speaking about how he trained Sengamalam, Rajagopal said, “Elephants are trained using the positive-reward system. There are a few command words which we ensure that the elephants are familiarised with. For Sengamalam, I used jaggery as a reward, and every time she obeyed a command, I would reward her with jaggery. So, even now, when she perfectly obeys my command, she gets her piece of jaggery. We mahouts rarely use violence. Maximum of elephants will get trained using the reward-system itself.”

Many have also said that a complete ban on the practice of temple elephants is not possible, as it is a deeply rooted cultural practice. “The reason why many animal welfare organisations are fighting this practice is that they want to end this domestication of elephants and instead build sanctuaries for them. They want to make money from these sanctuaries by making these elephants a matter of exhibition. The elephants are very safe now in temples, and they will be tortured if they’re put in sanctuaries. Therefore, this practice should not be stopped,” Saraswathi concluded.

While the courts have still not decided whether the domestication of elephants for temples should be continued or not, Mahouts and some animal activists still strongly believe that this practice should continue. For mahouts and the priests in temples, the elephants are like the deity himself/herself. They do not differentiate between humans and the elephant, and in fact, take more care of the animal as they create a special bond over the years. If this practice is prohibited, then it would mean that another Hindu tradition is attacked and ceased from existence.

Click here to subscribe to The Commune on Telegram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.