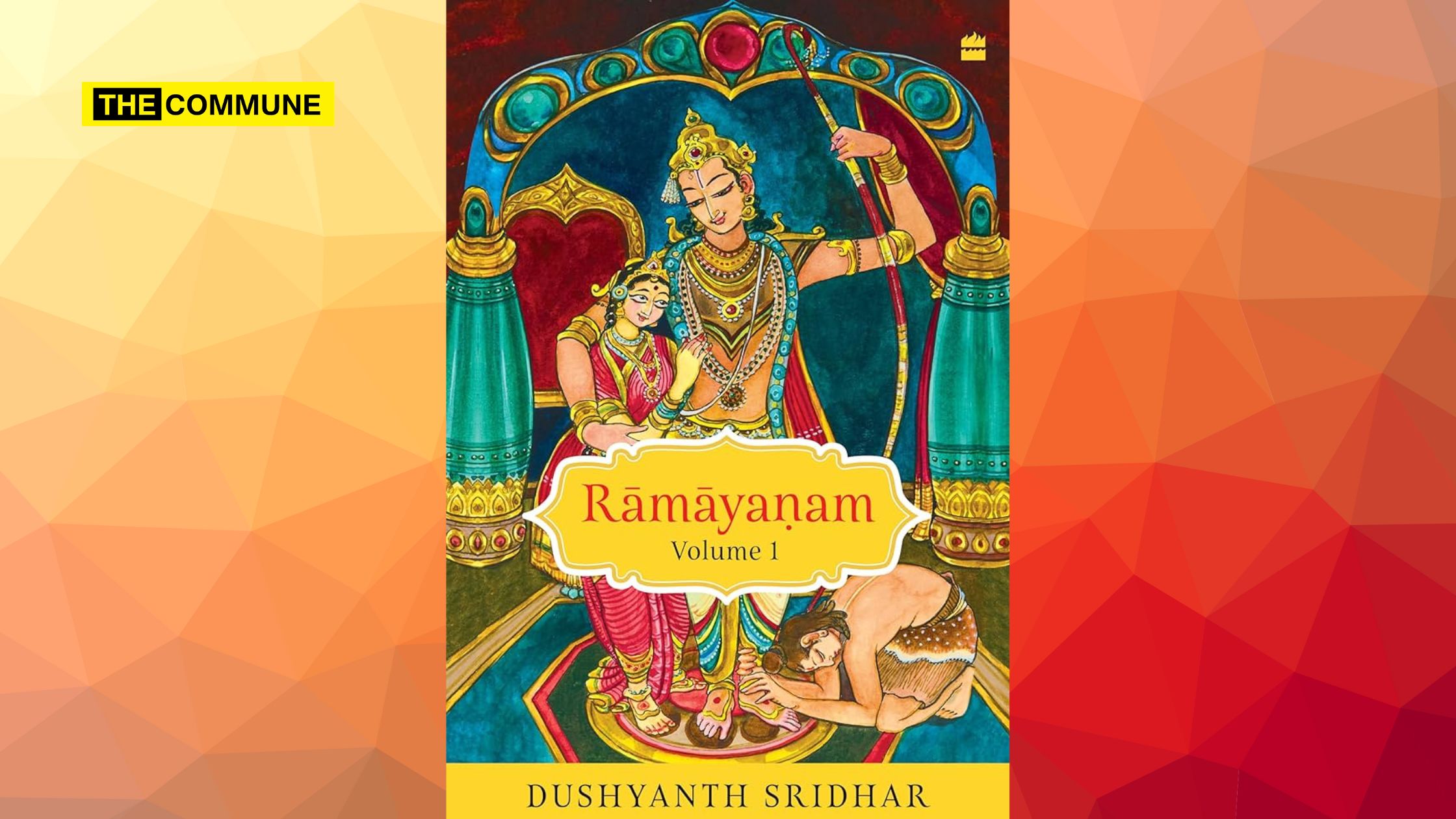

As a believer in the timeless wisdom of the Ramayana, I recently had the pleasure of getting a copy of ‘Rāmāyaṇaṁ – Volume 1’, the latest literary endeavour by celebrated speaker Dushyanth Sridhar. This much-anticipated book has generated significant buzz since its announcement, and I was eager to delve into its pages and share my thoughts on this insightful work.

Bharatha, the land of Sanatana Dharma, worships the itihasas equal to the Paramatma, for it provides the path towards Dharma. From time immemorial, the Ramayana, or Rāmāyaṇaṁ as it is called in some languages, has held a very high place in the hearts and temples of this divine land. The legendary life of Sri Rama inspires generations even today with lessons on life, Satya, and Dharma. Sri Rama’s Prāṇa Pratiṣṭhā has reinvigorated this blessed land and infused new energy into the general populace.

In the preface of Dushyanth Sridhar’s ‘Rāmāyaṇaṁ’, the author quotes multiple references like Adhyatama, Adbhuta, Ananda Ramayana, various Puranas, and commentaries from various Acharyas. The list cited in the preface is quite exhaustive and overwhelming. However, the author does make a specific claim. Quoting from the book, “Interesting aspects of the above works have been incorporated in this book in a way that there is no digression from Valmiki’s text”. This review will be based on this tenet, i.e. what is the augmented information compared to the original Valmiki Ramayana, and how does it aid the overall reading experience, especially of an English reader with no background on Itihasas and Puranas?

‘Rāmāyaṇaṁ’ starts from the Uttara Kanda, where Sita is enjoying her pregnancy with Sri Rama just before the catastrophe occurs in the form of her exile into the woods. Valmiki’s background story is also provided to set the context for the following narrative. Ramayana is shown to be composed by Valmiki in consultation or discussion with Narada. The dialogue between Valmiki and Narada is a recurring feature of this book. Many portions of the book are explained in dialogues. The book describes the events leading up to the birth of Sri Rama and his illustrious brothers, along with a background story of Shanta & Rishyashringa. The feats of Sri Rama and Lakshmana during his time with Vishwamitra, followed by Sita – Sri Rama vivaha, form the book’s next part. The book captures the events leading up to his exile, Dasaratha’s death, and ends with Bharatha carrying ‘padukas’ back to Ayodhya. From a classical point of view, it captures the complete essence of Bala Kanda and Ayodhya Kanda, along with a backdrop story from Uttara Kanda.

In the following few sections, I try to capture the book’s standout features and underwhelming aspects.

Standout Features in Rāmāyaṇaṁ

From the onset, there are some standout features of the book. The author has consciously utilised Samskruta words like Rakṣaka, Candra, Candana, etc. This makes the reading much more authentic, though it may differ slightly for those unfamiliar with IAST terminologies. However, it should be noted that many terminologies are quoted without a translation or meaning, leaving the reader in a conundrum. For example, the word “prappati” is used extensively throughout the book. However, the meaning or definition of this word isn’t explained for the reader to comprehend the overall significance or establish the context.

While the use of Samskruta words is excellent, the proximity of a few words like rakṣaka and rākṣasa could easily be missed, if not read closely. Perhaps the anglicised version or the meanings may have helped better in these situations.

The illustrations by Keshav are masterful and a delight to look at. In fact, they are one of the better parts of this book. The inscriptions and illustrations of carvings from temples are yet other standouts. This department’s research depth is exemplary and needs to be lauded. The reading experience could have been augmented by translating the Samskruta verses from these inscriptions. The missing translations could be a put-off to those not familiar with Samskruta.

Shortcomings in Rāmāyaṇaṁ

I had very high expectations about this book, but unfortunately, there were a few shortcomings. Initially, I had planned to provide a detailed explanation for each of the specific instances. Still, I fear that the same would make this review a very lengthy one and perhaps deter the reader from reading. Possibly, it merits a separate specific discussion where the focus would primarily be on the reviewer’s differences with the author’s version. However, I will capture the most critical, underwhelming aspects of the book.

Ramayana Dates

There has been a fair bit of controversy in the social media world about the dates of Ramayana being set around 5100 BC. Skanda Purana – Prabhasa Kanda clearly outlines that Sri Rama was born in the 24th Chatur Yuga, which would put the time quite a long way back and not anywhere close to 5100 BC.

caturvinśē yugē rāmō vasiṣṭhēna purōdhasā

saptamō rāvaṇasyārthē jajñē daśarathātmajaḥ

I feel the book’s divinity wouldn’t have been lost if the dates were not included. However, by introducing the dates, unnecessary confusion and diversion of attention are created in the readers’ minds, which certainly should have been avoided.

Divergences From Valmiki Ramayana

The author has introduced many stories and anecdotes from Srimad Bhagavatha Purana as part of the narrative/dialogue between various epic characters in Rāmāyaṇaṁ. These stories are not part of the traditional telling of Valmiki Ramayana, and hence, the book would have benefitted from references that inspired these additions to the flow. Many stories of the original Valmiki Ramayana are condensed into the flow while making space for additions from other sources like Bhagavatham.

In one of the earlier chapters, it is quoted that Sri Rama implored Brahma to capture his biography to be written in verse. I presume this could be coming from Adhyatma Ramayana, but the author doesn’t clarify the source of such differences. Such instances leave the reader in a state of confusion, which I believe is a downfall of this book.

In the chapter on “Vishwamitra’s tutelage”, the author quotes Vishwamitra waking up Sri Rama by saying that Kausalya is fortunate to have a son as illustrious as Rama and ordains him to perform the daily duties. However, a very critical point was missed in this context. The verse from Bala Kanda, sarga 23 is as below:

कौसल्या सुप्रजा राम पूर्वा संध्या प्रवर्तते |

उत्तिष्ठ नरशार्दूल कर्तव्यं दैवमाह्निकम् ||

This verse is the opening line of the very famous Sri Venkateshwara Suprabhatham, a common morning prayer in Hindu households. I am quite surprised and shocked that the author missed adding this reference.

Sampradaya Views

In the narrative, there are many references where the author tries to promulgate the views of a specific sampradaya, with deft statements like Shiva, a Bhakta of Narayana, or Shiva realising Narayana through his inner eye. When the author claimed that this version of Ramayana is close to the original, it should have been written equanimous with no biases or specific views of a particular sampradaya. If this was the objective, the author should have called out the same. By introducing these nuanced references, the author may diverge from his stated goals. One shouldn’t forget the timeless wisdom of Yajurveda, i.e. Shiva and Vishnu are the same, and those who try to find differences don’t truly understand them.

शिवाय विष्णु रूपाय शिव रूपाय विष्णवे |

शिवस्य हृदयं विष्णुं विष्णोश्च हृदयं शिवः ||

यथा शिवमयो विष्णुरेवं विष्णुमयः शिवः |

यथाsन्तरम् न पश्यामि तथा में स्वस्तिरायुषि|

यथाsन्तरं न भेदा: स्यु: शिवराघवयोस्तथा||

Language of Rāmāyaṇaṁ

Our itihasas often describe unconventional births and procreation methods among kings and Rsis. These practices of yore require delicate phrasing to maintain their dignity. Unfortunately, the author’s choice of words in certain instances is less than ideal.

For example, when describing Kalmashapada’s inability to have a son and his request to Vasishta, the author uses rather a blunt language, stating, “Vasishta impregnated Madayanti”. This story could have been dealt with better narration when compared with other books on the same topic. This can significantly affect the reader’s experience.

The author’s tendency to explicitly describe intimate acts is also somewhat surprising. Although coitus is undeniably an integral part of human evolution, using overly direct terminology such as “ejaculation of retas” can be off-putting to some readers. A more nuanced approach would have been more appropriate for discussing these sensitive topics.

Ambiguous References

Throughout the book, there are many instances where Rama and Sita are made self-aware or identified with Narayana and Lakshmi. This is extended to the brothers of Rama, who are identified with Sudarshana, Adi Sesha, and Shanku. I presume these references are mainly derived from Adhyatama Ramayana, where Sri Rama’s divinity is established, and Sri Rama is self-aware.

Towards the end of the book, i.e. culminating parts of Ayodhya Kanda where Rama counters the philosophical tenets of Jabali, the author introduces the reader to Buddha and Baudhas. In Ayodhya Kanda, Sarga 109, various instances of the terms “Buddhyaya” or “Buddhim” are present, which pertain to intelligence or somewhat misleading aspects of the same. However, it was a bit shocking to read the concept of Buddha in the flow of Ramayana. Perhaps the author could have included references from where these sections are derived.

Possible Political Inclinations?

If one looks at the overall construct of the book, one can’t help but observe a recurring pattern throughout the book. Most of the inscriptions quoted are from Tamil Nadu. The verses quoted from inscriptions are also from Tamil Nadu. There are multiple references to Dravida desha or Dravidian women throughout the book. The pinnacle of this undercurrent comes in the context of Gajendra Moksha, where the author establishes the story of Rsi Agastya but extends the same to the establishment of Tamil language, Dravida desha being called Tamilakam and the grammatical treatise, Agattiyam.

While the author can establish their views and extend the narrative as deemed fit, the above doesn’t augur in the context of the stated objective of being an amplified version of Valmiki Ramayana. These casual references inserted into the narrative reeks of a more political motive of establishing the deep connection of Tamil Nadu with Ramayanam. While this is a noble objective, the same should have been stated clearly in the preface rather than the nuanced positioning within the epic.

Conclusion

Rāmāyaṇaṁ had set very high expectations based on the high-profile launch and the author’s celebrity status. The divergences could have been explained better with adequate and informative references.

References:

Srimad Valmiki Ramayana – Gita Press

The Valmiki Ramayana (Critical Edition) – Bibek Debroy

http://valmikiramayan.pcriot.com/

Srimad Bhagwatham – Gita Press

Sanskrit Ramayana other than Valmiki’s – Dr. V. Raghavan

The Ramayana in Classical Sanskrit & Prakrt Mahakavya Literature – Dr. V. Raghavan

Skanda Purana – Sri Jayachamarajendra Grantaratnamala series

Gee Vee is an engineer and avid fan of itihasas, puranas and books.

Response to the review from Dushyanth Sridhar is as below:

On Ramayana Dates

The paragraph about the Ramayana dates that the reviewer has written. As such, I have not discussed anything about the yugas, the duration of every yuga, Chaturyuga, etc in the text of my book, nowhere it has been discussed. Nor have I criticized the version of the Puranas or the Itihasas and upheld the research Jayashree Saranathan has done research which is much better than the Puranas. I have quoted Jayashree’s name stating she is the one who has given the dates. Her dates have been mentioned in the footnotes, that’s all. The concept of a Chaturyuga especially the number of years 43 lakh 20,000 years being the Chaturyuga, the 24th Chaturyuga where the Ramayana happened is different.

All this is not found in Valmiki Ramayanam itself. From Bala Kandam to Uttara Kandam, there is no mention of it. It is found in a Purana and between itihasas and Puranas, itihasas are given more respect than the Puranas. When I say more respect, more authentic because they are regarded as direct history or recording. So nowhere in the Ramayanam itself, there is a discussion of the 24th Chaturyuga, where the Chatur Yuga being 43 lakh 20,000 years, nothing of that sort, it comes only in the Purana. I have not analyzed the dates or anything of that sort. In fact, in one of the paragraphs within the text of the book, I mentioned that I think it’s Lakshmana vakyam towards Rama, Rama now we are living in the times of Treta, but your administration makes me feel that there is more than Dharma in it like the Krita Yuga. So I’ve clearly mentioned this as Treta, this as Krita, and all of that in the text. Because I’ve mentioned clearly that we are living during the times of Treta Yuga, Rama, but you make us feel as if we are living in the times of Krita Yoga, because this has been extracted from a line of Vedanta Deshika’s Raghuveera Gadyam which says “Tretayuga pravarthitha Karta yuga vritthantha.”

On Venkatesa Suprabhatam verse

With respect to the verse “Kausalya Supraja Ramapurava Sandhya Pravathathe”, this is a verse from Valmiki Ramayana where Vishwamitra wakes up Rama in the early hours of the morning. So the reviewer asks why didn’t I make reference to Venkatesha Suprabhatam. There is no need. The Venkatesha Suprabhatam of the 14th century where Prativaadhi Bhayangara Mannan imports the verse from Valmiki Ramayana – Kausalya Supraja Rama and from the next verse only he starts composing which is “Uttishtottiṣṭha gōvinda uttiṣṭha garuḍadhvaja”. So, I don’t think there is any need to add the reference of Venkatesha Suprabhatam anywhere in the book, because I don’t pick up any verse from Venkatesha Suprabhatam. This verse is from Valmiki Ramayana. And the comment whatever I’ve written is explaining those lines is from the commentator Periyavachan Pillai’s commentary of the 13th century and Govinda Raja’s commentary of the Bhushana.

Rama and Sita as Narayana and Mahalakshmi

The original Valmiki Ramayanam has six commentaries and one of the largest of the six and probably the grandest is Govinda Raja’s commentary called Bhushana. Nagesha Bhatta’s commentary Thilaka is good but it is not as big and as deep as Govinda Raja’s. So there, Govinda Raja makes very clear references to Rama as the avatar of Narayana. Narayana akhilaheya pratyaneekatharaha samastha kalyana gunatmakaha, jagatchakshuhu, So he calls him the one who controls all the functions of the world, the one who is the Antaryami or all Devatas. So I’ve used that particular line stating that Narayana who is the Antaryami of all, thereby even when Shiva’s made reference, I have used that. So it is conforming to the commentary of Govinda Raja.

Within Valmiki’s original Ramayanam itself (Yuddha Kandam), there are multiple open and hidden references to Rama and Sita as Lakshmi and Narayana. When Mandodari praises Rama,

व्यक्तमेष महायोगी परमात्मा सनातनः |

अनादिमध्यनिधनो महतः परमो महान् ||

तमसः परमो धाता शङ्खचक्रगदाधरः |

श्रीवत्सवक्षा नित्यश्रीरजय्यः शाश्वतो ध्रुवः ||

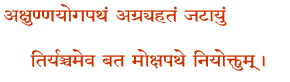

She says that I see you as Paramatma holding Shanka Chakra as Narayana who has got Mahalakshmi on his chest. And when looking at Jatayu, he says “Gachcha lokaanuktamaan”. I grant you Moksham, go to that place from which there is no return Jatayu, which is Mokshapradattvam. So, all these have been taken into verses by Kuresha in the 11th century in his work called Atimaanushasthavam where he says,

He clearly talks about the Moksha granting status and calls Rama as Narayana. So Valmiki in many instances, has given subtle references to their Parathvam.

Valmiki Ramayana inspiration

I have mentioned in the book flap in the front blurb as well as in the preface that I have completely been inspired by Valmiki his commentators, and many other works, and I had to use that little right of being the author of this book, to use some creativity to stitch those ends.

Dravida/Tamil

Coming to the word Dravida Draavida, please note that in Ayodhya Kandam, Aranya Kandam also, when Lakshmana sees a branch full of flowers, Rama refers to them and states these are carrying so many flowers, like the women from the south of India (Dakshinayaam), who have flowers on their heads. So, there is a clear reference to the South Indian culture.

Gajendra Moksham Reference

This instance involves Agastya who was in the south of India, and Bhagavatham, we have a clear reference that it happened by the banks of river Tamirabharani. The word Dravida comes in Bhagavatham as well (Utpanna dravidesaaham) and Vedanta Desika has written Dramidopanishad Tat Parya Ratnavali. So Dravida Shishu says Adishankara. So the word Dravida Dramila Draavida has been in vogue in the Samskruta literature.

Even in Ramayanam, Sindhudouveeraaha Draavidaha, I remember this verse where the word Draavida comes. So, this word has been there. The word Tamizh may not explicitly occur in any of the granthas because that is the name given locally to this language. But I had to introduce that because in Sundarakandam when Hanuman says, “Instead of Samskrutham, I will talk to her in a Madura Basha”, many of the Acharyas in the south of India interpret that to be Tamizh. So, Tamizh must have existed then. And also Tamizh must have been a language completely soaked in Bhakti. Because Bhagavatam says “Utpanna dravidesaaham”, Bhakti grew and was born in the state of Dravida, which means where Tamizh is spoken and around that period Tamizh must have also come up.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.