Rajinikanth starrer Vettaiyan, directed by agenda-driven director TJ Gnanavel known for his lies in Jai Bhim, has once again peddled lies in the latest film. The opening scene itself begins with a glorification of school dropout Macaulay – the British politician who served the death blow to Indian knowledge systems. In the film, Amitabh Bachchan is seen praising him for bringing “social justice and equality in education.”

Did Macaulay Bring Education To India? Let’s Bust This Propaganda

Thomas Babington Macaulay, known for his influential role in shaping British colonial education policy in India, introduced English education with a clear agenda to promote Western superiority and undermine native culture. The British education system that followed presented the West as aspirational, asserting British superiority in science, arts, and even morals, while instilling an inferiority complex among Indians.

Macaulay’s policies sought to make Western culture and knowledge appear more desirable, gradually leading to a loss of connection with India’s rich intellectual and cultural heritage. This colonial mindset contributed to a long-lasting cultural shift, where many educated Indians began to emulate Western tastes and values, often at the expense of their own traditions.

But Did He Bring Education To India?

The lie in the film claims that no educational policy existed before the British came to India, and Macaulay was instrumental in creating one.

By this logic, one wonders how China, Japan, or other Asian countries received their education.

In the 1830s, Macaulay became an MP in the British Parliament. Around that time, the British East India Company was ruling several parts of the world. They were asked to analyze the loopholes in the justice and education system. So, Macaulay visited India for four years as he was part of the Supreme Council. The lies propagated revolve around this recommendation.

However, this propaganda was initiated by evangelists in the 1970s and 80s. Let us understand this further.

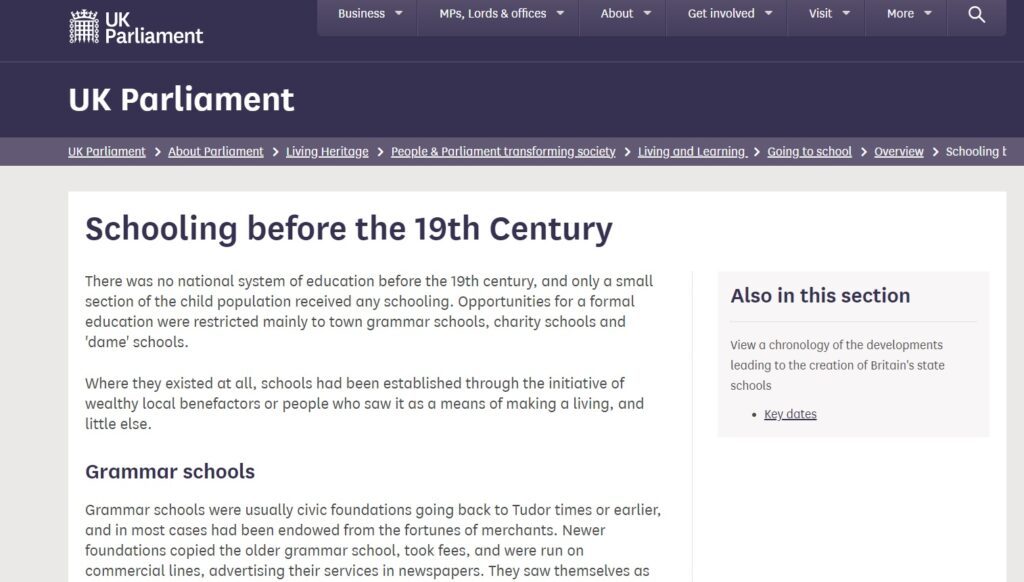

If we look at the UK government website, it is pretty clear that there was no national education policy in the UK until the late 19th century. Then how would it have come to India?

Around 1854, the EIC continued to face significant losses in the colonies it was ruling so the education policy was shifted to the control of the Crown.

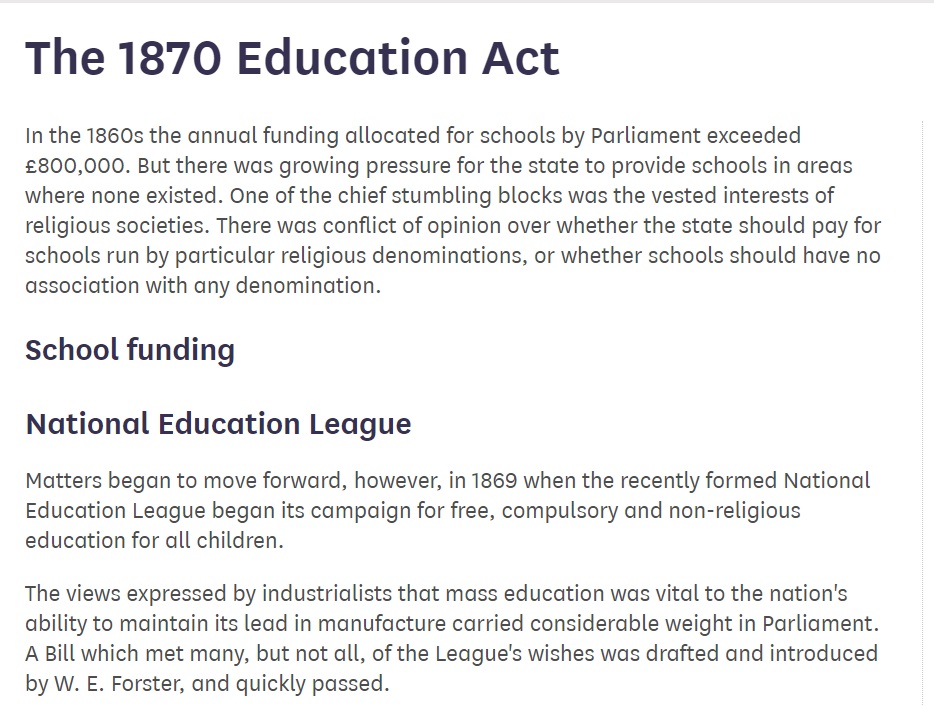

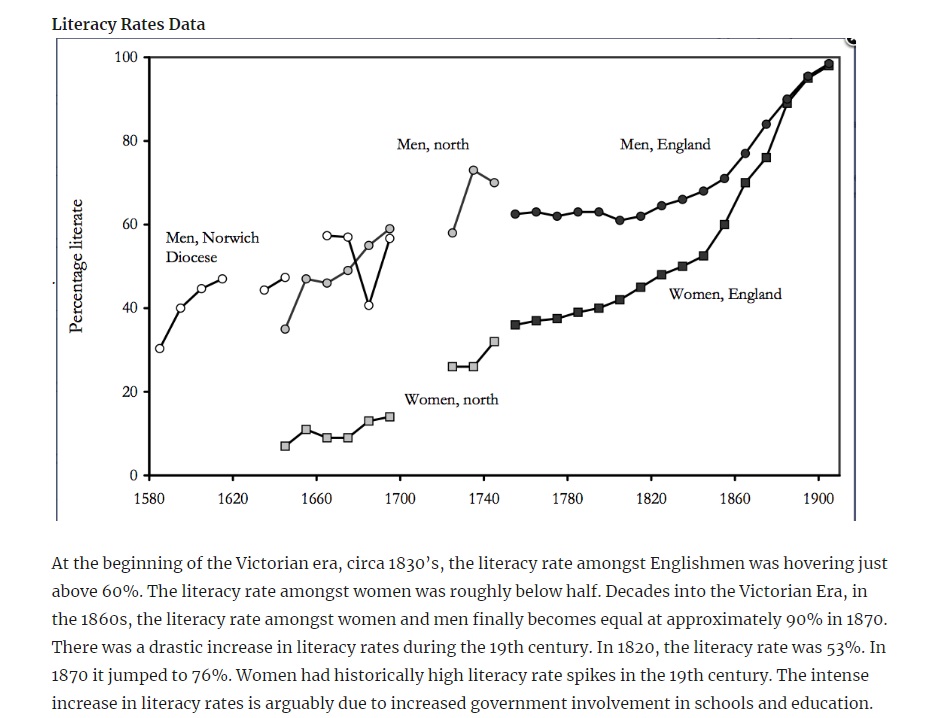

The Education Act, a national education policy was brought in the country (Britain) in 1870. Data indicates that before the 1870s, 40% of women and 60% of men were literate (not educated). Before 1870, grammar and Christian studies were taught to the people, but no national educational policy existed. Even when Macaulay was alive and working in the Parliament, no educational policy existed.

In the Act brought in 1870, the UK began clearly distinguishing the content taught.

In his Minute on Education, Macaulay says, “I have no knowledge of either Sanscrit or Arabic.–But I have done what I could to form a correct estimate of their value. I have read translations of the most celebrated Arabic and Sanscrit works. I have conversed both here and at home with men distinguished by their proficiency in the Eastern tongues. I am quite ready to take the Oriental learning at the valuation of the Orientalists themselves. I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. The intrinsic superiority of the Western literature is, indeed, fully admitted by those members of the Committee who support the Oriental plan of education.”

What is interesting is that Arabic countries or any other country in the world never accepted what Macaulay said. Only Tamil Nadu seems to celebrate this man, and that is due to the evangelists there.

Did Indian Education Even Need Macaulay

Not Really. India had a thriving indigenous learning system long before Macaulay knew how to read and write.

In The Beautiful Tree, a pioneering work by Dharampal that elaborates on Indigenous Indian Education in the Eighteenth Century, reveals how education was accessible to a broad section of Indian society, including the underprivileged castes of today, contradicting the colonial narrative that education was exclusive to the elite.

British records from the early 19th century documented over 11,000 schools in the Madras Presidency, including the Bellary and South Arcot districts. These schools catered to a large population segment, showing that education was not confined to urban centres but was also present in rural areas.

Records from 1835 in Bengal and Bihar indicate that there was a school for almost every 100 to 150 families, suggesting widespread access to education. Data from the early 1820s in the Bombay Presidency showed that nearly 30% of the boys in the region were in school.

What Macaulay Did To Indian Education

Macaulay was pivotal in reshaping India’s educational landscape during British rule. His 1835 educational minutes established English as the medium of instruction, effectively diverting funds away from Indian educational systems and resources.

Macaulay’s “downward filtration method” prioritized the education of a small, elite class of Indians who were to be “Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, opinions, morals, and intellect.”

This policy aimed to create a class supporting British interests, eroding traditional Indian values and knowledge systems. Despite Macaulay’s confidence in the efficacy of his educational reforms, the missionaries later discovered that while they had distanced some Brahmins from their cultural roots, widespread conversion and acceptance of British ideologies were largely unsuccessful.

The long-term impact of Macaulay’s reforms resulted in the marginalization of many Indian castes, a loss of cultural identity, and a prevailing reliance on Western models for education and governance, leading to a regression in national consciousness and self-awareness.

The truth is, India had a rich, thriving, egalitarian education system before the British set foot on our soil. Gurukuls, universities like Nalanda and Takshashila, flourished long before Macaulay’s ancestors could read or write.

What Communist Marx Had To Say About Macaulay

TJ Gnanavel calls himself a communist. But what did Communist icon Karl Marx say about the same Macaulay? Karl Marx referred to Macaulay as a ‘systematic falsifier of history’. Historians criticized his approach for being one-sided and complacent. Later historians also saw his views on non-European cultures as explicitly racist.

If we come to Japan, yes, there was an influence there as well. However, after the 1940s, they completely trashed that system and introduced a new policy – almost copying the American education system but focusing more on learning the subjects in the mother tongue. That is why, in the 1970s, its economy took off quite well. They rejected the British or colonizer’s system and made one alone.

So, who was responsible for the education system in India? It is noteworthy that Macaulay died in 1859, even before a national education system existed in the UK.

மெக்கலே படிக்க வச்சானா? டேய் tj ஞானவேல் – மெக்கலே 1859 செத்துட்டான். அடுத்த 10 வருடம் பின் தான் பிரிடீஷ் national education act வந்ததே 1870ல் தாண்டா.. பின்ன ஒரு எப்படிடா? அதுவும் 1835 ல east india company இருக்காண்டா.. அறிவு இருக்கா மேன்? ஆதாரம் தாடா!

படம் பார்க்க வந்தா உன்…

— Maridhas (@MaridhasAnswers) October 13, 2024

Dadabhai Naoroji

Dadabhai Naoroji—does this name ring a bell? Naoroji, an Indian, was the first Asian to be elected to the British Parliament and served a brief stint between 1892 and 1895.

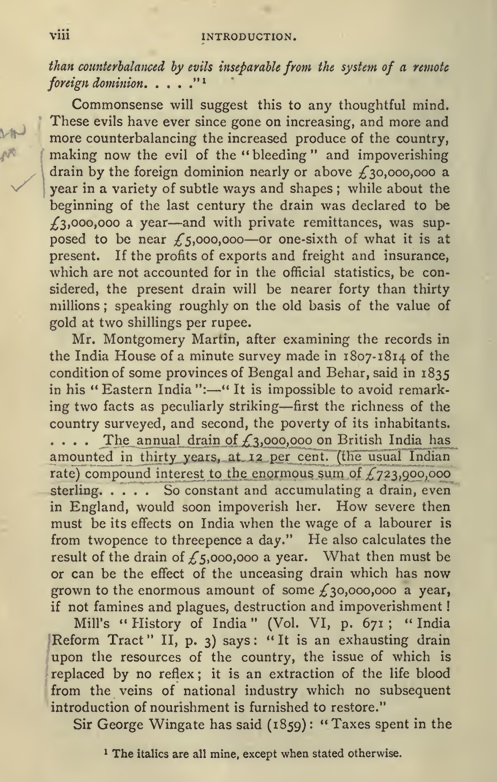

Dadabhai Naoroji, an early critic of British imperialism, began challenging the idea that colonial rule benefited India after witnessing Britain’s prosperity in 1855. His economic analysis over two decades exposed the “drain of wealth” from India, arguing that British rule impoverished the country and exacerbated deadly famines. As a British colonial subject, he ran for Parliament, advocating for India’s political change from within Westminster. Elected in 1892 as a Liberal MP, he condemned British rule as oppressive and pushed for reforms, though his efforts were largely ignored. Despite setbacks, Naoroji remained optimistic, allying with progressive movements and continuing to demand justice for India. In his London Speech of 1871 he summarises, “To sum up the whole, the British rule has been: morally, a great blessing; politically, peace and order on one hand, blunders on the other; materially, impoverishment, relieved as far as the railway and other loans go. The natives call the British system “Sakar ki Churi,” the knife of sugar. That is to say, there is no oppression, it is all smooth and sweet, but it is the knife, notwithstanding. I mention this that you should know these feelings. Our great misfortune is that you do not know our wants. When you will know our real wishes, I have not the least doubt that you would do justice. The genius and spirit of the British people is fair play and justice. “

Following this, the British started considering Naoroji’s statement. Around the 1890s, when a financial crisis hit them, they found a solution to both problems—they started building hospitals and schools to give them basic employment and aid them. In such a scenario, the Indian Railways came to be. However, the Indians were paid paltry sums compared to their British colleagues.

It is also a fact that when the British left India in 1947, only 6% of Indians were educated. This only proves the agenda peddled by the likes of Gnanavel who are ably abetting with the missionaries who brought in the “education” system to evangelize the Indians.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.