For the year 2018-19, India saw a record food grain production of 285.21 million tonnes. The fourth advance estimate of production of food grains for the year 2019-20 placed the total food grain production at 296.65 million tonnes i.e., 11.44 tonnes more than what was achieved in 2018-19. The first advance estimates for the current year 2020-21 (kharif only) has put the total food grains production at 144.52 million tonnes.

Now, that is a lot of food that we have but where to sell them?

Earlier, farmers had to sell their produce at the local APMC mandis which are heavily politicised and controlled by commission agents and middlemen. These commission agents and middlemen having political influence gulp a major portion of the profit leaving the producer (farmer) parched.

But with the new farm laws, the farmers have been empowered by giving them the choice to sell their produce where they get a better price. Those who want to sell in the APMC can continue to do so and those wanting to explore the market have been given the choice to. What these farm laws have done is to create one more route for the farmer to sell the produce and realize higher incomes.

Also, how much can the government alone buy? Even after the government procures grains through Food Corporation of India (FCI) to ensure food security and to maintain a buffer stock, tonnes of food grains remain left to be sold. Doesn’t it make sense to make these grains available to individual private small and medium businessmen to be sold in the open market for consumption?

So, if these farm laws are a boon to the farmer then why are the ‘farmers’, especially those from Punjab protesting in Delhi?

Here are some numbers that sheds some light.

Food grain production and GVA

The 5 states that topped food production for the year 2018-19 are:

|

State |

Total Food Grain Production (million tonnes) |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

5.4 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

3.2 |

|

Punjab |

3.1 |

|

Rajasthan |

2.1 |

|

Haryana |

1.8 |

(Source: RBI Data Handbook)

The Gross Value Added in Agriculture and Allied Industries (GVA) by these states for the year 2018-19 are:

|

State |

GVA in Agriculture and Allied Industries (₹ in lakh crores) |

|

Uttar Pradesh |

2.2 |

|

Madhya Pradesh |

1.6 |

|

Punjab |

0.89 |

|

Rajasthan |

1.5 |

|

Haryana |

0.81 |

(Source: Agricultural Statistics at a Glance 2019)

From the data, it can be seen that Punjab, which produces 2 million tonnes more food grains than Rajasthan has a GVA much less than the latter. Haryana which produces 1.7 times less food grains has a GVA almost equal to Punjab’s.

Even states with lesser food grain production compared to Punjab have a better GVA in agriculture and allied sector. Andhra Pradesh which recorded a food grain production of 1 million tonnes (3.1 times more than Punjab) had ₹1.8 lakh crores GVA. Tamil Nadu with 1.03 million tonnes food grain production recorded a GVA of ₹1.2 lakh crores in the agriculture and allied sector.

Now, the question that arises is – how come a state, that benefitted the most from the green revolution emerging as the wheat bowl of India have lesser GVA in agriculture sector when compared to other states. Who is eating away the money in between?

The middlemen/commission agents, known as ‘arhtiyas’ in Punjab.

The powerful middlemen and the hapless farmer

The middle men not just eat into the farmer’s gains but also into the nation’s GVA. They take large chunks of the profits as commissions that should ideally reach the farmer.

A report by Tribune India notes how the presence of middlemen in Punjab is killing the aspirations of farmers to increase their incomes. One of the farmers was quoted saying that they are compelled to sell their produce to middlemen who sell it at double the rate in the market leaving the farmer with nothing.

In 2013, the vegetable growers of Punjab decided to explore avenues for direct marketing of their produce. “We are exploited by middlemen, who take large chunks of our profits as their commission. To get rid of this menace and to achieve various benefits from the central government policies for the vegetable growers of the country, we have joined hands with the Vegetable Growers Association of India” Jaswinder Singh Sangha, newly elected president of Punjab Vegetable Growers Association was quoted saying in the Business Standard.

The middlemen walk away with huge commissions for virtually doing nothing. They have no significant role in procuring the rice or wheat produced by the farmer. All that these middlemen do is provide for contract labour in the mandis. The FCI which procures the food grains from the farmer at Minimum Support Price (MSP) routes its payment to the farmers through the ‘arhtiyas’ who take a 2.5% commission on the payment.

And these arhtiyas are a powerful lobby in Punjab. Back in 2010, when the FCI decided to directly pay the farmer bypassing the middlemen, they threatened to boycott procurements from the farmer and successfully lobbied the Punjab government. In the next few days, the FCI retracted its order saying “direct payment order of minimum support price to farmers is kept under abeyance for Punjab and Haryana up to Sept 30, 2011 or till further orders”.

A 2015 study by Punjab Agricultural University elaborates on the modus operandi of the commission agents. It states

The most common mode of exploitation of farmers is the indirect payment system, wherein the commission agents receive payment of the sale of produce from farmers. Other tools of exploitation like non-registration as moneylenders, system of indirect payment of farm produce, non-issuance of J-form, slip mechanism, multiple licences and multiple business constitute the modus operandi through which the business of commission agents flourishes.– Page 59, Commission Agent System: Significance in Contemporary Agricultural Economy of Punjab, Economic and Political Weekly.

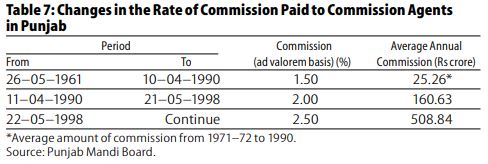

The study also explains how paying farmers through the commission agents, an exploitative mechanism remains the backbone of the procurement system in Punjab. Commission agents with their political clout have managed to increase their commission rates from 1.5% to 2.5%, time to time by pressuring the state government.

Another issue that the study points out is that most of the commission agents are also moneylenders not registered with the government, acting detrimental for both the farmers and the government. “The prime motive of commission agents for not getting registered is to evade taxes, pursue malpractices like exorbitant rate of interest, use of blank promissory notes, and so on.”, the paper says.

The commission agents also follow a practice of called ‘damami’ during times of low productivity by which these commission agents charge the farmer equivalent to the previous year’s commission, irrespective of the low produce.

There are also other ways through which the farmer is essentially bound to the middlemen. The slip mechanism is one. Farmers in need of money for their day-to-day needs are not paid cash but are given ‘slips’ for obtaining items from their owned or connected shops where goods are sold at a much higher price than market rate.

The study notes

“..the commission agents earn about Rs 1,034 crore, amounting to an average of Rs 5.11 lakh for each commission agent in the state. Thus, during 2012–13 the commission agents earned about Rs 2,407 crore from various sources. Each commission agent received about Rs 12 lakh per annum by acting as commission agent. Above all, the commission agents enhance their income through slip mechanism, supply farm inputs and domestic articles and act as middlemen in all transactions related with farming and domestic articles, cheating in weighing and pricing, etc. There is a need to inhibit the commission agents which have now become an integral part of the agrarian economy, and are flourishing at the expense of the government and farmers in Punjab.” – Page 61, Commission Agent System: Significance in Contemporary Agricultural Economy of Punjab, Economic and Political Weekly.

None of the mainstream media has brought this out in light. Worse, some of them have portrayed this oppressive relationship between the arhtiyas and the farmer as something that is ‘friendly’. An Indian Express article dated December 3 noted that the arhtiyas and farmers ‘enjoy a friendship and bonding’ going back decades adding that they take care of the farmers’ financial loans and timely procurement at ‘adequate prices’.

Political parties like the Congress and Shiromani Akali Dali (SAD) too, as expected are on the side of the middlemen. Punjab Chief Minister Amarinder Singh had justified that the arhtiya system was the “backbone of Punjab’s successful agricultural model, with the farmers and arhtiyas sharing a very close bond”.

Farm laws – shifting the balance in favour of the hardworking farmer

The farm laws passed by the Centre will break the monopoly of the commission agents and relieve the farmer from their mercy. With the definition of ‘trade area’ getting changed to ‘any place of production, collection, and aggregation of farmers’ produce’, farmers can directly sell their produce to anyone they want at the farm gate. By giving the option to the farmer to directly trade with anyone in the market who offers a better price, the middlemen who have been gobbling up the farmer’s profits will be hit.

There are a total of 28,000 licensed arhtiyas in Punjab who wield great social, economic and political power. As soon as the farm bills were passed by the Parliament, the Arhtiyas Association passed a resolution condemning the Centre. It is these arhtiyas and the farmers tied to them (and instigated by them?) who are behind the protests in Delhi, not the hapless farmer who is longing for getting out of the clutches of these arhtiyas.

Ofcourse, those comfortable with the arhtiya system can continue to sell their produce through commission agents. Mandis will continue to function and trading through these state government run mandis will continue as before. The Centre has categorically stated that MSP will not be affected by these laws and that the government will continue to procure from the farmers at MSP rates. In fact, the government paddy procurement from Punjab accounted for 20.28 million tonnes or 67% of the 31.8 million tonnes of paddy bought across the country as per the Press Information Bureau release.

Many experts have called for reducing the role of middle in procurement and agricultural trade. Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan too in 2014 said the there is a need to wedge the gap between what the farmer gets and what is paid by the household by reducing the role, number, and monopoly power of middlemen as well as by improving logistics.

HS Dhaliwal, Director of Punjab Agricultural Management and Extension Training Institute (PAMETI), said that agriculture in the state had achieved production heights but farmers who toiled hard make meagre profits as middle men walk away with major share.

He said that there was a pressing need to reduce the role of middle men and encourage farmers to sell their produce directly to consumers.

The new farm laws aims to do precisely that – empower the poor farmer by giving him the option to directly sell the produce to any trader or consumer who offers a better price. This will not just shift the balance of power towards the poor farmers of Punjab but also help in increasing the state’s share of the GVA in agriculture and allied industries.

But this true picture has been lost in the noise behind the protests by ‘farmers’ who are just people wanting the exploitative status-quo to continue.

What the government should now do is to bring out this picture and address the genuine concerns of farmers entangled in the arhitya system. It should not let the protests get hijacked by inimical forces to become another Shaheenbagh episode.

This article was inspired from the Twitter thread of Krishna Kumar Murugan (@ikkmurugan).

Farm Bill politics Thread:

Indian Food grain Production for the year 19-20: Top 5 states

🚜 Haryana : 17.8 Lakh Tons

🚜 Rajasthan : 23.2 Lakh Tons

🚜 Punjab : 29.9 Lakh Tons

🚜 Madhya Pradesh : 33 Lakh Tons

🚜 Uttar Pradesh : 55 Lakh TonsProtests only in Punjab

— Krishna Kumar Murugan (@ikkmurugan) November 30, 2020