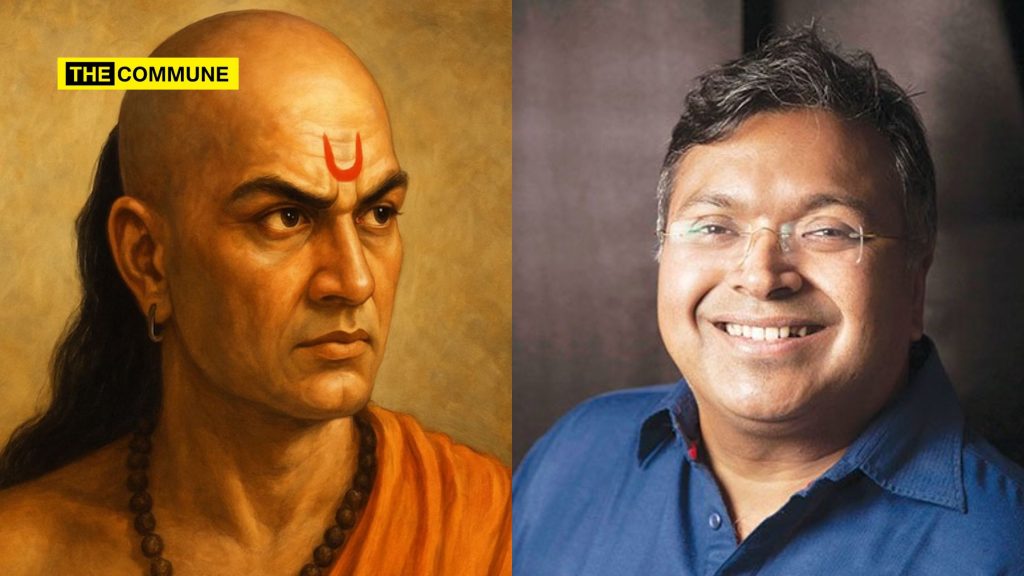

On 9 November 2025, mythological fiction author Devdutt Pattanaik, known for his fantasy book series, posted about an article he wrote for The New Indian Express.

The article was titled “A fantasy called Chanakya”, with a byline. “The legend of Chanakya is simply this trans-civilisational script recast as Indian patriotism, with a dash of casteism”

This is not just wrong but mischievous ideological narrative building by Pattanaik.

The Impossible Standard Of Proof

Pattanaik’s central premise is that “there is absolutely no historical evidence that a man called Chanakya ever lived.” He demands contemporaneous, archaeological proof – a coin, an inscription, a royal edict bearing his name.

This standard is just unrealistic. If we were to apply it universally, we would have to dismiss the existence of most major figures from ancient history.

Alexander the Great: Our primary accounts of his life were written 300-400 years after his death by Greco-Roman historians like Arrian and Plutarch. There are no contemporary Indian records of his invasion.

The Buddha: There is zero contemporaneous evidence of his birth, life, or teachings. His existence is reconstructed from texts compiled centuries later by communities with a vested interest in promoting his legacy.

Jesus Christ: The earliest New Testament gospels were written decades after his crucifixion, by followers, not neutral observers. There is no Roman record of his existence from his lifetime.

Would a “selfie from Pataliputra” be enough for Pattanaik? Ancient history is not a court case where you get inscriptions on demand to prove something ‘beyond a reasonable doubt.’ It is a forensic science that pieces together probabilities from fragmented, often biased, and later sources. By Pattanaik’s logic, the fields of classical and ancient history would cease to exist.

The Plurality Of Sources: A Consensus Of Traditions

Pattanaik dismisses the sources on Chanakya as “later Buddhist and Jain chronicles and Sanskrit plays… imagined after 500 AD.” This oversimplifies the whole thing.

What makes Chanakya credible is that so many unrelated traditions mention him. He appears in:

- Buddhist texts like the Mahavamsa (5th century CE), which draw on older Sri Lankan commentaries.

- Jain texts like the Parishishtaparvan (12th century CE), which meticulously detail Chandragupta’s conversion to Jainism and his death by sallekhana (ritual fasting) in Shravanabelagola—a tradition supported by local inscriptions and enduring worship.

- Sanskrit literature, most notably Vishakhadatta’s political drama Mudrarakshasa (c. 4th-8th century CE), which takes the Chanakya-Chandragupta story as its central plot.

These are not a single, monolithic “Brahminical” narrative. They are competing accounts from traditions that were often doctrinally opposed to each other. Yet, they all converge on one central fact: a brilliant, shrewd Brahmin named Chanakya (or Kautilya) was the mastermind behind the Mauryan empire’s rise. For these diverse traditions to independently affirm his pivotal role is powerful evidence of his historicity, not a reason for dismissal.

The Arthashastra: A Text With Layers, Not A Forgery

Pattanaik points to references to Chinese silk and Roman gold coins in the Arthashastra to claim it was composed around 200 AD, “almost 400 years after Mauryan rule.”

This is a classic case of mistaking the leaves for the tree. Mainstream scholarship, including historians like R. C. Majumdar and D. D. Kosambi, agrees that the core of the Arthashastra is a product of the Mauryan period. The text we have today likely underwent centuries of transmission, with later scribes and scholars adding commentaries, examples, and updating terminology—a process known as interpolation.

The presence of a later interpolation does not invalidate the entire text’s origin. The sophisticated detailing of a complex bureaucracy, taxation, and espionage in the Arthashastra aligns perfectly with what we know of the vast Mauryan state from Ashokan edicts and Megasthenes’ account.

The “Mentor Trope” And Selective Cultural Skepticism

Pattanaik argues that the Chanakya story is merely a common “narrative trope” found globally, comparing it to Merlin and King Arthur, Hemachandra and Kumarapala, or Vidyaranya and the founders of Vijayanagara.

This argument backfires spectacularly. The universal presence of the “wise mentor” archetype doesn’t prove these figures are fictional; it points to a recurring historical and sociological reality. Powerful rulers have often relied on the counsel of learned advisors.

The Buddhist monk Nagasena debated and guided the Indo-Greek king Menander, as recorded in the Milinda Panha.

As Pattanaik himself notes, the Phagpa Lama was a preceptor to the Mongol emperor Kublai Khan.

Why are these relationships, or that of Aristotle and Alexander, not dismissed as pure fiction, while Chanakya’s is deemed a “fantasy”? The bias is hard to miss: only Indian civilizational heroes, particularly those valorized in a “Hindu” or “Brahminical” context, are subjected to this level of deconstructive scrutiny. The mentor-king trope is accepted as a plausible historical reality everywhere except in this specific Indian instance.

The Agenda Of Selective Historical Destruction

The most telling part of Pattanaik’s thesis is what he doesn’t attack. He will never write a column titled “A fantasy called St. Thomas,” despite the complete lack of contemporary evidence for the apostle’s legendary journey to Kerala in 52 CE; a story crucial to the identity of many Indian Christians.

He will never question the existence of the Buddha, whose life is documented only in texts written centuries after his parinirvana by his devoted followers. This selective application of “skepticism” exposes the game: the target is not historical inaccuracy, but specific elements of the Indian/Hindu historical consciousness that do not align with a particular ideological worldview.

It is possible that Devdutt and his ilk would also claim Nalanda university was destroyed by Brahmins based on some spurious later period texts; however, they will not believe Chanakya existed because it comes from later period texts. The standard of evidence is flexible, bending to serve a pre-determined narrative that often seeks to undermine traditional Indian institutions.

History Is Not A Weapon

Devdutt Pattanaik’s article is a masterclass in historical nihilism disguised as progressive scholarship. By imposing an impossible standard of proof, ignoring the consensus-building methodology of historians, and applying his skepticism with glaring selectivity, he does not enlighten but obscures.

The figure of Chanakya—the brilliant, ruthless strategist who orchestrated the fall of the Nanda empire and the rise of India’s first major imperial power—is supported by a robust cross-traditional consensus. His legacy, encoded in the Arthashastra, resonated across Asia for over a millennium, with his aphorisms being translated and treasured from Nepal to Tibet and Sri Lanka.

To dismiss this as a “convenient fiction” is not just bad history; it is an attempt to sever a people from a pillar of their historical memory. If there’s any fantasy here, it’s the idea that you can throw out every old source that doesn’t fit your politics.

In the end, what Pattanaik peddles is not history but a deracinated sermon meant to shame Indians out of their own civilisational confidence. Chanakya endures not because of blind patriotism, but because multiple traditions, texts, and centuries of scholarship recognise the magnitude of his political genius.

Reducing him to a “fantasy” says nothing about Chanakya and everything about the ideological compulsions of those desperate to unwrite India’s past. A civilisation that produced the Arthashastra does not need validation from armchair mythographers masquerading as scholars. The real fantasy is the belief that selective skepticism can erase a figure who has lived robustly in the subcontinent’s historical, literary, and political memory for over 2,000 years.

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.