Dravidianists – be it those in the echelons of power, in cinema or in the media – often paint Tamil Nadu as a progressive state, lauding its removal of caste-based surnames as a sign of modernity and egalitarian society. But what value does this “removal of caste surnames” have when caste remains entrenched in people’s minds?

The film Nandan starkly exposes this contradiction, but it hasn’t received the same support or visibility as propaganda films by directors like Pa. Ranjith or TJ Gnanavel. This is because Nandan challenges dominant Dravidianist political narratives, refusing to toe the line that aligns with their ideology.

At the heart of the film is Koozhpaanai, a hardworking man from a marginalized community who serves Koppulingam, a powerful Panchayat leader. Koppulingam, having won two unopposed Panchayat elections, is devastated when his seat is reserved for a Scheduled Caste candidate. Unable to run himself, he installs Koozhpaanai as a puppet candidate, expecting to retain control behind the scenes.

In the previous election, Koozhpaanai prayed to his guardian deity Nondisamy to ensure that his master Koppulingam wins without competition. This is the norm in the village – the villagers internally decide who’s their President, and only they are nominated – to win unopposed.

This is a poignant shot – not only are the downtrodden people ill-treated in this village, even their deities are ignored, dwelling within dilapidated conditions. Even the Gods are not spared of discrimination.

But Koppulingam and his bedridden father do not treat Koozhpaanai with even basic respect. He is allowed to enter only the back room to tend to the bedridden old man, but never the main house. The one time he is called in, it is for Koppulingam to prove a point to Koppu’s relatives. Koozhpanai dines with them, too naive to even understand that he’s being dehumanizingly used as an insult to Koppulingam’s relatives.

Koppu and his relatives fight amidst them to field a reserved candidate for the new Panchayat elections. Koppu fields the loyal Koozhpaanai. The two downtrodden people are unaware why they are being used as pawns in the landlord’s fight. This shot shows how they are almost treated as roosters in a c0ckfight to boost their egos.

Eventually Koozhpaanai wins – but this is only namesake. A gimmick for the world – just like dropping surnames, with no real impact on the ground. Koppulingam is felicitated in the temple asusual, as if he is the President, whereas Koozhpaanai stands outside, a helpless placeholder for the laurels after their utility is done.

A villager considers saving the President Koozhpaanai’s number in his phone itself as insulting – a modern form of untouchability. Koozhpanai is sent away with bogus reasons, and is not allowed to sit in the President’s chair which is “reserved” for Koppulingam.

The President still toils in the field, doing his master’s bidding, while his White Veshti – a symbol of his Presidentship – uselessly hangs in a tree. It is a poignant shot – that signifies democratic positions are merely ornamental and are useless in front of social power.

When Koozhpaanai’s name is finally added to the village notice board as President, he and his wife are horrified to find it smeared with cow dung—a bitter representation of how little respect he commands, even in his own office. This is the moment we learn his real name: Ambedkumar, a name that invokes the legacy of Ambedkar, yet carries no weight in the reality of village life.

For Independence Day, Ambedkumar rehearses his speech, dreaming of hoisting the flag as Panchayat President. But it’s Koppulingam who seizes the “right” to raise the flag, humiliating Ambedkumar in front of the village children, government officials, and his own son. This scene takes place behind the back of the statue of Thiruvalluvar, whose famous couplet “Pirapokum Ella Uyirkum”— often misused and overquoted by ‘progressive’ and ‘Dravidianist’ politicians. Thirukural here is as decorative and useless as Ambedkumar’s President post – because both are merely namesake, and not implemented or enforced in reality. Even though Dravidianists portray themselves as ‘progressive egalitarians’ to the outside world, their real casteist mindset is entrenched.

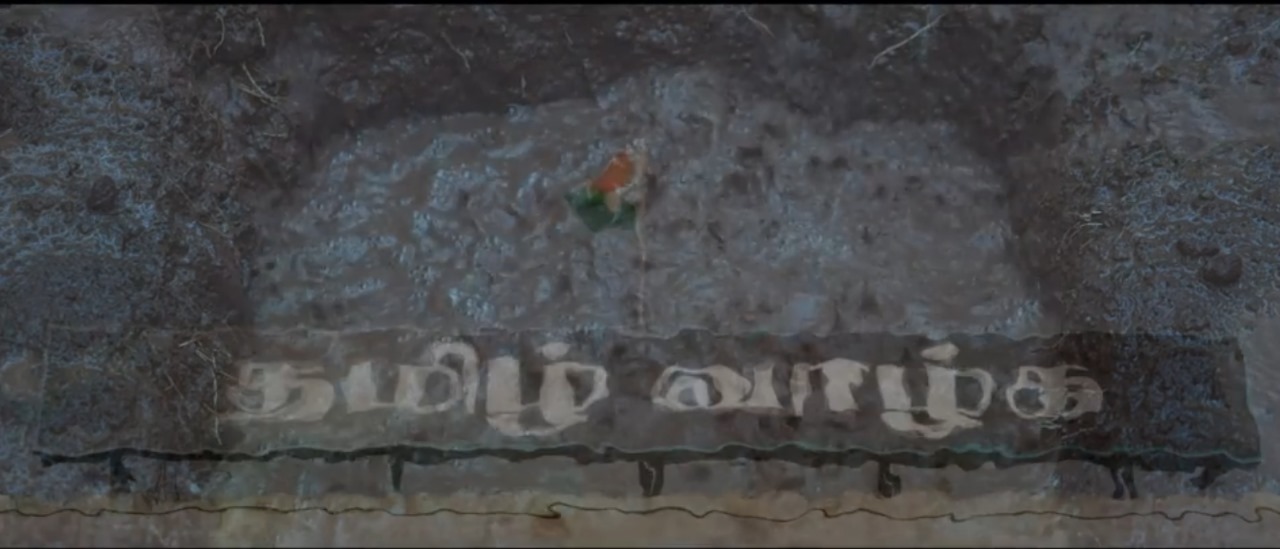

Another powerful scene critiques the state’s caste politics: Ambedkumar’s grandmother is refused cremation in the common ground due to caste restrictions, even in the midst of severe rain. Forced to bury her, Ambedkumar’s act symbolizes the burial of social justice itself. With social justice buried to the ground, appears the next image – “Thamizh Vaazhga” written over Govt Building. Of what use are all the praises to Tamil – when the downtrodden don’t even have rights to respectfully cremate their dead? Do Tamils consider themselves equal? Using Tamil pride to win elections, but doing next to nothing to change ground reality of Tamils – this is the sad state of Tamil Nadu politics where even basic human rights are denied to the real marginalized.

Ambedkumar’s presidency is further undermined when he’s violently beaten simply for sitting in a chair in the government office while Koppulingam stands. The film paints a grim picture of a village governed by caste, not law, where even a Panchayat President can be humiliated with impunity. When a sandal is thrown at Ambedkumar within the government office, no one intervenes—a stark commentary on the failure of law enforcement and governance.

Real-life testimonials from Panchayat Presidents of reserved constituencies drive home the film’s message: these leaders are mere figureheads, devoid of power or respect, trapped in a system that perpetuates their subjugation. The final image of the film tells it all – when powerful landlords are in, not just the downtrodden, but even their leader Ambedkar’s photo isn’t allowed inside offices. Only when real power flows down to the downtrodden, is he let in. No amount of gimmicks can change reality.

The film’s rejection by the Dravidianists stems from its unapologetic portrayal of caste dynamics. Ambedkumar, a devout man who worships Nondisamy and seeks blessings from Lord Muruga, stands in contrast to the atheistic, progressive ideals typically championed in Tamil Nadu’s political cinema. In the ‘puratchi’ movies milieu, such a hero is unacceptable and becomes untouchable. By not validating this film or giving it the attention it deserves, is a another form of untouchability by the Dravidianist castes.

Image Credits: Amazon Prime No copyright infringement intended as images are used for fair use only – criticism or review.

(This article based on the X thread by Tamil Labs 2.0)

Tamil Labs provide high quality Tamil Content written interestingly in English.

Subscribe to our Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram channels and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.