Following Union Minister for Culture and Tourism Gajendra Singh Shekhawat’s statement that more scientific studies and concrete conclusions are needed on the Keeladi excavations, DMK chief and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin reignited the North-South Aryan-Dravidian cultural debate. Instead of directly releasing the official radiocarbon dating results from the U.S.-based Beta Analytic laboratory — which claims Keeladi’s antiquity — Stalin responded by citing news reports and peer-reviewed articles as scientific evidence, turning the exchange into petty political barbs.

Taking to his official X account, Chief Minister Stalin declared, “Even when confronted with carbon-dated artefacts and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) reports from International Laboratories on the #Keezhadi excavations, they continue to demand “more proof.” And here is the “Proof”. But on the contrary, despite strong opposition from respected historians and archaeologists, the BJP continues to promote the mythical Sarasvati Civilisation. They do so without credible evidence, while dismissing the rigorously proven antiquity of Tamil culture. When it comes to #Keezhadi and the enduring truth of Tamil heritage, the BJP-RSS ecosystem recoils — not because evidence is lacking, but because the truth does not serve their script. We fought for centuries to unearth our history. They fight every day to erase it. The world is watching. So is time.”

Even when confronted with carbon-dated artefacts and Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) reports from International Laboratories on the #Keezhadi excavations, they continue to demand “more proof.”

And here is the "Proof".But on the contrary, despite strong opposition from… pic.twitter.com/VxJzAJpSpK

— M.K.Stalin (@mkstalin) June 13, 2025

What Does The Latest Times Of India Report Say?

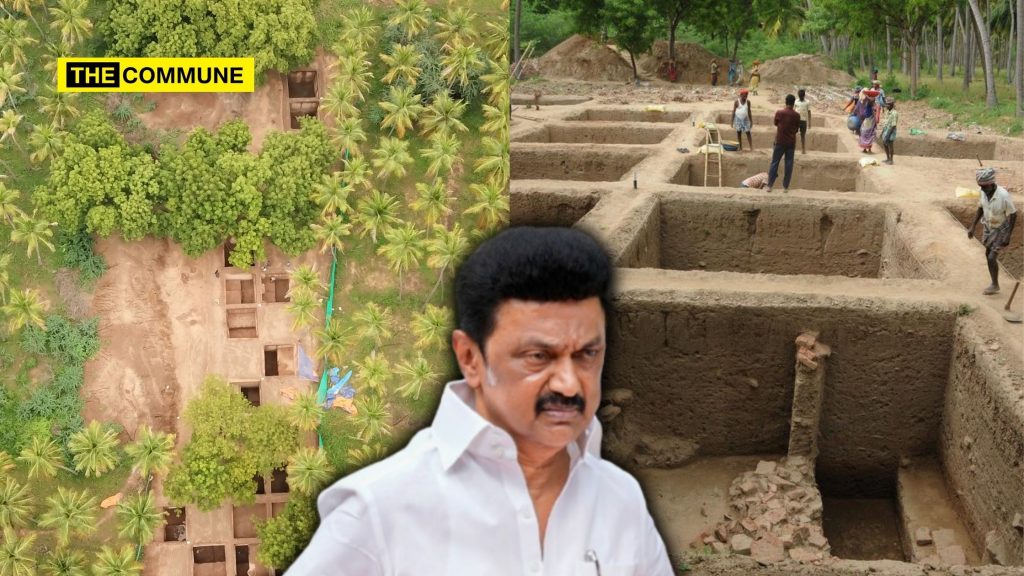

Backing up his statement, Stalin shared a report from The Times of India, detailing that the Keeladi site near Madurai has yielded definitive radiocarbon dating results from the U.S.-based Beta Analytic lab, placing the settlement as far back as the 6th century BCE. This timeline makes it contemporaneous with the urban growth along the Gangetic plains. Of the 29 samples dated since the 2017-18 excavation season by the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology, the earliest goes back to 580 BCE and the most recent dates to around 200 CE. These findings suggest that Keeladi was a thriving urban and industrial center for nearly 800 years. Brick structures aligned with Sangam Age descriptions support this conclusion. Archaeologist K. Rajan, who serves as an advisor to the archaeology department, confirmed that while the majority of samples above the brick foundations date from after the 3rd century BCE, those beneath them reach as far back as the 6th century BCE, placing Keeladi on par with the Gangetic urbanisation — what is often referred to as India’s “second urbanisation.” Notably, 12 of the 29 samples fall in the pre-Ashokan period, prior to the 3rd century BCE.

New research also appears to be moving closer to reconstructing the face of the ancient Tamils who lived in the Keeladi region. A skull recovered from the Kondagai burial site is being used for anthropometric analysis and 3D reconstruction. Rajan stated that from this, researchers intend to determine the person’s age, diet, gender, and facial features. This is part of a wider collaborative research initiative involving over 20 institutions from India and abroad, including the University of Liverpool, University of Pisa, the Field Museum in Chicago, the French Institute of Pondicherry, IIT Gandhinagar, and Deccan College. The goal is to fully reconstruct life as it existed in Keeladi around 580 BCE. While Deccan College is currently analyzing animal bones found at the site — including remains of bulls, buffaloes, goats, cows, sheep, dogs, pigs, antelope, and spotted deer — researchers at Madurai Kamaraj University are engaged in DNA analysis that will shed light on migration patterns and admixture within the ancient Keeladi-Kondagai population.

Altogether, the scientific work done at Keeladi has yielded 29 confirmed radiocarbon dates, helping to establish a robust archaeological timeline. The discovery of potsherds inscribed with Tamil-Brahmi script has now pushed the known origin of that script to the 6th century BCE. Additionally, the recovery of gold and ivory objects, seals, beads, terracotta dice, and industrial tools paints a vivid picture of a sophisticated, urbanised, literate, and artisan society. According to R. Sivanandam, Joint Director of the State Archaeology Department, Keeladi was a manufacturing and trade center situated along an ancient commercial route that connected the eastern port of Alagankulam to Muziris on the western coast via Madurai. Yet the original name of this settlement remains unknown. References in Sangam literature to foreign trade, jewelry, urban life, and monumental architecture are now being understood as historical records rather than poetic imagination. Indologist R. Balakrishnan remarked that Keeladi has validated the lived realities described in Sangam texts. Even artifacts such as terracotta and ivory dice, referenced in the literary anthology Kalithogai, have been recovered from the site.

Importantly, Keeladi is not the only site in Tamil Nadu yielding early historic dates. Rajan pointed out that sites like Kodumanal, Porunthal, Sivagalai, Adichanallur, and Korkai have also produced dates as early as the 6th century BCE — with Korkai dating back to 785 BCE — suggesting that the process of urbanisation in Tamilakam was widespread and not confined to a single location. Despite ten excavation seasons, only about 4% of the 110-acre Keeladi site has been explored. To preserve and display these findings, the Tamil Nadu government has launched a museum dedicated to Keeladi, and an on-site museum — the first of its kind in India — is in the planning stages. “Tamil Nadu suffered from official archaeological neglect for far too long,” Balakrishnan said, “until Keeladi awakened a deep interest among Tamil people.” Rajan echoed this, stating that Keeladi has fundamentally transformed how archaeology is approached in the state.

Is Keezhadi Older Or Sarasvati Valley Civilization?

The Sarasvati Valley Civilization, often grouped with the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), is one of the world’s earliest urban cultures. It flourished between 3300 BCE and 1300 BCE, with its mature phase from 2600 BCE to 1900 BCE. Spread across present-day Pakistan and northwestern India, particularly along the Indus and the now-extinct Sarasvati (Ghaggar-Hakra) rivers, this civilization boasted advanced town planning, drainage systems, trade networks, and a script that remains undeciphered. Major cities like Harappa, Mohenjo-daro, and Dholavira reflect a sophisticated way of life thousands of years ago.

In contrast, the Keezhadi site—located near Sivaganga in Tamil Nadu—dates back to a much later period. Excavations have uncovered layers dating to 600 BCE to 300 BCE, with some nearby sites like Konthagai suggesting habitation from around 800 BCE. Findings include brick structures, fine black-and-red ware pottery, Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions, and evidence of an organized society with urban characteristics. Keezhadi offers a glimpse into the early historic period of Tamilakam, potentially aligned with the Sangam era.

K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, the archaeologist who led the first two excavation phases from 2014 to 2016, submitted a report in 2023 to the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) stating that the Keeladi site had been continuously inhabited between the 8th century BCE and the 3rd century CE. The ASI, however, disputed his findings, asserting that the site could not be dated earlier than 300 BCE and demanding a revision. Ramakrishna stood by his original conclusions.

Is Stalin Rewriting History To Establish Dravidianist Racial Supremacy Theory?

The issue with Stalin’s statement is that he has cited reports that relies solely on peer-reviewed articles, while critics claim that no scientific evidence has been officially released so far. As of now, radiocarbon dating indicates that the Sarasvati/Indus Valley Civilization is significantly older than the Keeladi Civilization. The Sarasvati Civilization is dated roughly between 3300 and 1300 BCE, whereas the Keeladi site dates to around 580 BCE, according to recent radiocarbon findings.

The Keezhadi excavation, while academically significant, is increasingly being co-opted by the DMK and its ideological allies as a tool of political propaganda rather than a subject of scholarly exploration. Instead of celebrating it as a testament to the rich cultural tapestry of ancient India, the DMK seeks to isolate Keezhadi from the broader Indian civilizational narrative—projecting it as evidence of a racially and culturally superior “Dravidian” past, supposedly untainted by “Aryan” or Vedic influence.

This distortion feeds into the long-debunked Aryan-Dravidian racial dichotomy, a colonial-era myth that modern historians and genetic studies have dismantled. Yet, the DMK revives it with renewed zeal, using it to denigrate the Sarasvati (Indus) Valley Civilization, portraying it as “Aryan,” “northern,” and therefore alien, while casting Keezhadi as the cradle of an indigenous, independent Tamil identity.

This ideological project is not confined to academic discourse. It is echoed in political statements, such as Chief Minister MK Stalin’s recent assertion that “Tamil Nadu will remain out of Delhi’s control.” Such rhetoric is not mere federal posturing—it signals a deeper separatist itch that runs through the core of Dravidianist politics. The narrative being pushed is clear: Tamil Nadu is not just geographically distinct, but civilizationally, racially, and culturally separate from the rest of India.

In this context, Keezhadi is being transformed from an archaeological site into an ideological weapon—used not to illuminate the past, but to redraw cultural and political boundaries. Far from fostering unity, the DMK’s narrative risks deepening divisions and reviving fault lines long buried, all in the name of Dravidian racial supremacy and political autonomy.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.