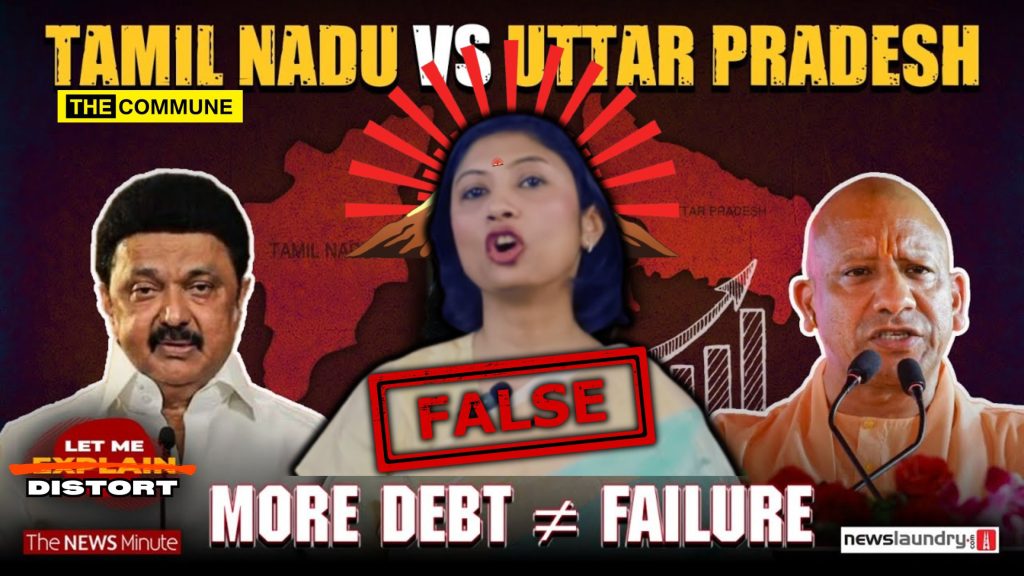

The claim that Tamil Nadu’s debt cannot be compared to Uttar Pradesh’s has emerged as the latest talking point in The News Minute’s Let Me Explain series. The episode asserts that those citing Tamil Nadu’s higher total debt are “misleading” the public and that, once “context” is applied, the State emerges not just fiscally sound but unfairly targeted by number-twisting critics.

A closer look at data however, reveals TNM’s propaganda style – selective framing, casual handling of numbers, and a typical leftist strategy – pre-empting legitimate scrutiny by declaring it “meaningless”.

Manufacturing a Victim Narrative

From the opening minute, the video frames the issue not as a fiscal debate but as a moral confrontation. Critics who point to Tamil Nadu’s higher debt are cast as peddlers of a “simple story of fiscal failure”, while the anchor positions herself as rescuing viewers from bad faith statistics.

Cross-state comparison itself is portrayed as inherently political and dishonest rather than a routine analytical tool used by the RBI, Finance Commission, PRS Legislative Research, and credit-rating agencies.

Instead of asking an obvious and legitimate question of whether Tamil Nadu’s debt trajectory comfortable and sustainable, the episode pivots to a defensive posture:

- Tamil Nadu is richer, more diversified and socially advanced than Uttar Pradesh.

- Debt is merely a “tool”, and richer states can naturally carry more of it.

- Therefore, highlighting absolute debt numbers is either economic illiteracy or deliberate misrepresentation.

So, questioning policy is treated as questioning Tamil Nadu. The show abandons analysis and assumes the role of advocate.

Sloppy Numbers, Blurred Timelines

Any serious explainer must first get the numbers right. This is where the episode falters badly.

The video cites Tamil Nadu’s debt at ₹9.29 lakh crore and its GSDP at ₹35.6 lakh crore, producing a debt-to-GSDP ratio of about 26%. But ₹9.29 lakh crore is not the 2024–25 actual debt—it is the projected outstanding debt by March 2026, as per the 2025 budget.

At the same time, the GSDP figure used is from earlier projections. The 2024–25 budget places nominal GSDP closer to ₹31.6 lakh crore.

This mixing of future debt, with older, higher GSDP estimates artificially softens the ratio. The viewer is never told which year these figures correspond to, or that they are projections rather than actuals.

For Uttar Pradesh, the episode uses round figures – ₹9.03 lakh crore debt and ₹30.8 lakh crore GSDP – which align with 2025–26 projections, again without disclosure. Crucially, PRS data shows that UP, like Tamil Nadu, is also targeting fiscal deficits within the 3% FRBM band. That similarity is conveniently ignored.

For a show that repeatedly accuses politicians of “reading numbers out of context”, this casual blending of timelines and estimates is not a minor oversight, it undermines the entire argument.

One Yardstick for Tamil Nadu, Another for UP

The episode insists that debt must be judged relative to economic size, growth potential, and revenue capacity.

This is sound economics. But it is applied selectively.

Tamil Nadu is praised for keeping its fiscal deficit near 3% of GSDP and raising roughly three-quarters of its revenue from own sources.

Uttar Pradesh, meanwhile, is reduced to a caricature: a poor state surviving on Union transfers. There is no discussion of:

- UP’s own FRBM compliance,

- its recent capex push,

- or improvements in tax effort—all documented in PRS and budget analyses.

If FRBM compliance and debt ratios are the benchmarks, they must apply equally. Instead, Tamil Nadu is acquitted under rules that UP is never even tested against. What is sold as “context” increasingly resembles narrative management.

Airbrushing Tamil Nadu’s Debt Risks

The video reassures viewers that Tamil Nadu’s debt ratio has “stabilised and is slowly declining”, citing projected marginal improvements from 26.6% to 26.4%.

What it does not mention:

Tamil Nadu’s debt-GSDP ratio had already climbed sharply before COVID-19, a trend flagged by the 15th Finance Commission as a medium-term concern.

Interest payments and committed expenditure viz, salaries, pensions, interest, consume a growing share of revenue, squeezing fiscal flexibility. This is documented in Tamil Nadu’s own budget papers.

COVID-19 is used as a moral alibi: borrowing limits were relaxed, states had to borrow, therefore post-2020 debt accumulation is treated as morally neutral.

But serious fiscal analysis does not end with COVID. It begins with what comes after structural costs, welfare commitments, and political competition. These are precisely the issues the episode avoids.

A neutral analysis need not claim Tamil Nadu is on the brink. It only needs to insist that being richer than UP does not exempt the State from scrutiny. The video refuses that nuance.

Declaring Scrutiny “Meaningless”

The choice of words is deliberate. The episode could have argued that cross-state debt comparisons are incomplete without context. Instead, it repeatedly calls them “meaningless” and “misleading”.

But comparisons of debt-to-GSDP, interest-to-revenue ratios, and contingent liabilities are exactly how fiscal stress is identified by bodies that monitor such risk. These metrics are not meaningless; they are starting points.

By declaring them meaningless, the show effectively immunises the Tamil Nadu government from benchmarking. That is not explanation, it is insulation.

Welfare, Outcomes, and the Cost Question

The episode’s strongest segment highlights Tamil Nadu’s genuine achievements: lower infant and maternal mortality, better health outcomes, higher school enrolment, and a higher HDI.

It argues, correctly, that these outcomes require sustained public spending, and that low debt elsewhere can signal under-investment rather than prudence.

But here again, nuance is abandoned. All spending is treated as productive and virtuous. There is no distinction between long-term, high-return investments, and recurring subsidies and politically timed schemes with unclear returns.

To even ask whether some schemes carry fiscal risk is implicitly treated as hostility.

Explanation or Advocacy?

There is a real and necessary conversation to be had about how state debt is discussed in India. Politicians routinely cherry-pick numbers. Citizens are rarely told what FRBM rules mean. Explain-style journalism can play a valuable role here.

But rebutting spin with counter-spin helps no one.

A good-faith explainer would clearly separate actuals from projections, apply the same benchmarks to all states, acknowledge both strengths and risks, and stop framing scrutiny as an attack on the State itself.

The News Minute episode gets one thing right: context matters more than raw numbers. But in its eagerness to defend Tamil Nadu from criticism, it slips into its own form of narrative control – framing legitimate fiscal questions into a morality tale of a misunderstood, virtuous government under siege. Explainers are meant to illuminate trade-offs and risks.

Regular readers of The Commune will recognise the pattern immediately – Let Me Explain is less about explanation and more about arranging the facts to suit a predetermined narrative.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.