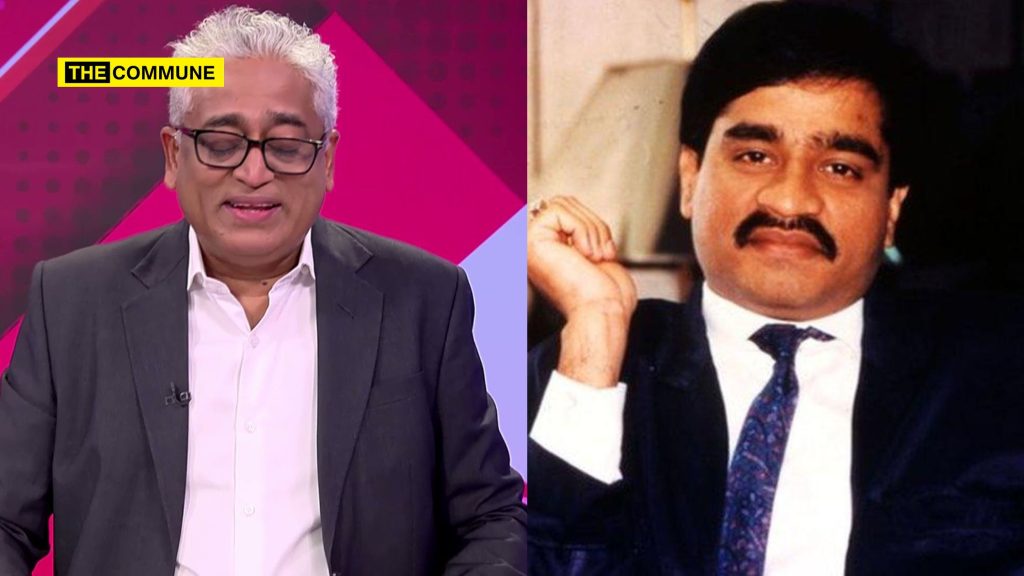

Rajdeep Sardesai, one of India’s most prominent journalists, has repeatedly come under criticism for his coverage of some of the gravest attacks on India, particularly the 1993 Bombay blasts orchestrated by Dawood Ibrahim.

The 1993 serial bombings killed 275 innocent people and injured thousands, leaving Mumbai traumatized. Yet, in his commentary, Sardesai often shifted focus away from the perpetrators and the terror network, framing the narrative instead around communal dynamics and the psychology of Indian society.

How many of you remember that Rajdeep Sardesai wrote an article praising and defending Dawood Ibrahim in 1993 soon after the Mumbai bomb blasts which killed 275 innocent people ???

This is how he whitewashes crimes against India pic.twitter.com/o4dRQShHbd

— Rishi Bagree (@rishibagree) September 25, 2025

Just after the blasts, Sardesai wrote an eloquent piece in Times of India back in 1993. He even wrote another piece sort of following up on the ’93 piece in 2013 in Hindustan Times.

Let’s understand the problem with both these articles.

Downplaying Dawood’s Role

Even though Dawood Ibrahim was already a prime suspect in the Bombay blasts, Sardesai emphasized that there was “no prima-facie evidence” implicating him and leaned heavily on the caveat offered by the Bombay Police Commissioner. By highlighting Dawood as a “mythical demon figure” in Hindu militant discourse rather than a criminal mastermind, Sardesai reframed the underworld don in less threatening terms.

In effect, he treated Dawood more as a controversial public figure in Hindu imagination than as a mastermind of a terrorist operation that caused massive loss of life in India. This approach inevitably diluted the perception of the 1993 blasts as a direct attack on India orchestrated by a foreign-backed criminal.

Shifting the Focus to Communal Victimhood

Instead of investigating the planning, financing, and ISI-Pakistan backing of the bombings, Sardesai pivoted the discussion to warning against stigmatizing the entire Muslim community.

He compared post-blast suspicion of Muslims to the treatment of Sikhs after 1984 or Marwaris in Assam, portraying the narrative more as a story of majoritarian hysteria than a matter of national security. While highlighting communal tensions is important, Sardesai’s emphasis came at the cost of underplaying the calculated, terrorist nature of the attack.

Reframing the Underworld as “Cosmopolitan”

Sardesai further argued that Dawood’s network was “cosmopolitan” and profit-driven, pointing out that several of Dawood’s top lieutenants, including Chhota Rajan, were Hindus. While technically true, this framing shifts focus away from the Islamist-terror link and Pakistani involvement, portraying Dawood less as a traitor working against India and more as a mere profiteering gangster.

Normalizing Muslim Alienation as the Root of Terror

Sardesai repeatedly contextualized terrorism as a reaction to Hindu-majority violence or state failure. For example, he linked Dawood’s transformation into an ISI-backed terrorist to the communal riots following the Babri Masjid demolition. Similarly, he drew analogies with the 1984 anti-Sikh pogroms and the 2002 Gujarat riots to argue that violence begets violence. While historical context is important, his narrative effectively justified Dawood’s terrorist actions as a sociological response rather than condemning them as crimes against India.

Praising or Defending Dawood?

Sardesai’s work sometimes borders on what critics describe as indirect defense. In the 2013 Hindustan Times article, he reminded readers that Dawood had once offered Toyota cars to the Indian cricket team in Sharjah if they beat Pakistan.

By portraying Dawood as a cricket fan and framing his actions as part of a broader “inconvenient truth” about riots and societal failures, Sardesai softened the image of India’s most wanted man. He questioned why Dawood became a terrorist, emphasizing the social and communal causes rather than the deliberate, planned betrayal of India orchestrated by Dawood and the ISI.

Selective Attention to Victims

In both the 1993 and 2013 writings, Sardesai highlighted victims of communal violence (1984 Sikhs, 2002 Muslims, Muzaffarnagar Muslims, Kashmiri Pandits) but largely ignored victims of Dawood-backed terrorism, such as the 275 people killed in the Bombay blasts. This selective framing centers on societal failings and communal stereotyping rather than addressing the deliberate targeting of Indian civilians by Dawood’s terror network.

Last Word

By downplaying Dawood’s criminality, reframing terrorism as a reaction to societal failures, and emphasizing communal victimhood, Rajdeep Sardesai’s coverage effectively whitewashed the 1993 Bombay blasts and other acts orchestrated by Dawood. While highlighting communal prejudice is valid, his approach shifts accountability from the perpetrators to Indian society, underplays the scale of terror, and at times even defends or praises Dawood indirectly.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.