When Chief Minister MK Stalin announced the Tamil Nadu Assured Pension Scheme (TAPS) for government employees, the Dravidian establishment and its ecosystem projected it as a historic pro-employee victory and a “20-year struggle fulfilled”. Employee unions linked to JACTTO-GEO publicly celebrated the announcement, distributing sweets and declaring victory.

However, a closer examination of the scheme’s structure, its fiscal implications, and comparable pension frameworks already in place elsewhere suggests that TAPS is neither a restoration of the Old Pension Scheme (OPS) nor a new innovation. Instead, it closely mirrors the Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) framework earlier outlined by the Union government – rebranded, repackaged, and politically timed.

What TAPS Really Is – And What It Is Not

Despite the political messaging, TAPS does not restore the pre-2003 Old Pension Scheme which the DMK had promised in its 2021 manifesto.

Under OPS:

- Employees made no contribution

- The government bore 100% liability

- Pension was fixed at 50% of last drawn pay

- Family pension and gratuity were structurally higher and predictable

TAPS is not a straightforward restoration of the pre-2003 Old Pension Scheme (OPS). It is a hybrid model, designed to look like OPS politically while retaining the contributory framework of the New Pension Scheme (CPS), and then loading the gap on to the taxpayer.

Key features of TAPS include:

50% assured pension – Government guarantees 50% of last drawn basic pay plus grade pay as pension for employees who joined service on or after 1 April 2003.

Employee contribution continues – Employees will contribute 10% of basic pay (plus DA) into the pension corpus, same as the existing CPS (Combined Pension Scheme)/NPS contribution.

State picks up the tab for the difference – Whatever the fund cannot generate to reach the 50% promise, the government will pay the balance from the budget, effectively socialising the risk.

Dearness allowance and family pension – DA on pension revised every six months, mirroring serving employees. Family pension fixed at 60% of the pension after the pensioner’s death.

Gratuity and minima – Retirement gratuity up to ₹25 lakh and minimum pension even for those without full qualifying service.

Scope and timing – Applies to the post-2003 CPS cohort, with implementation slated around 2027, subject to rules and notifications.

In simple terms: TAPS lets the DMK say “OPS is back” in election rallies, while on paper it remains a contributory-but-guaranteed scheme whose shortfalls will be plugged by the exchequer.

A Copy-Paste Of Unified Pension Scheme Launched By Modi Govt

What the DMK has announced closely aligns with the Unified Pension Scheme (UPS) proposed earlier by the Union government under Narendra Modi.

The UPS framework proposes:

- Pension at 50% of the average of last 12 months’ salary

- Family pension at around 60%

- Lump-sum retirement benefits

- A contributory model with government backstop

Several states, including Maharashtra, Assam, Uttarakhand and Chhattisgarh, have moved toward variants of this model. Others such as Rajasthan, Punjab, Jharkhand and Himachal Pradesh rejected it, choosing OPS instead.

Tamil Nadu did neither. Instead of formally opting for OPS or negotiating modifications through the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA), the DMK announced a state-level replica of UPS, branded as a fresh “assured” scheme.

The Real Price Tag: ₹13,000 Crore Now, ₹11,000 Crore Every Year – And Climbing

The numbers are not small. The fiscal implications are substantial.

One-time hit – TAPS needs a ₹13,000 crore one-time contribution to seed the corpus.

Annual recurring outgo – The government’s own briefings and multiple reports put the annual contribution at around ₹11,000 crore to start with – a figure that will rise automatically as salaries, DA and the retiree pool grow.

This lands on top of an already tight fiscal situation:

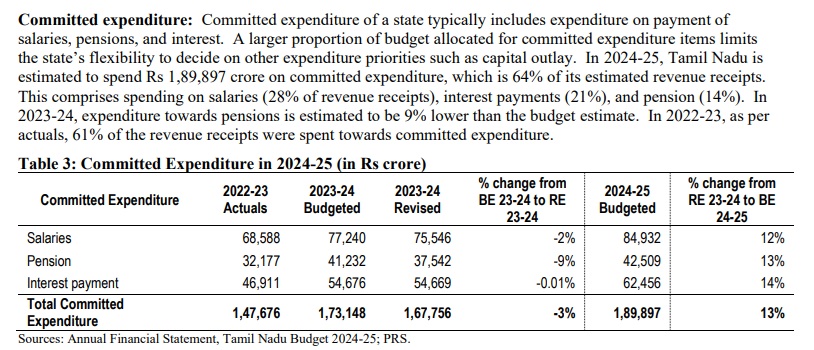

Analysis shows committed expenditure (salaries + pensions + interest) at about 64% of revenue receipts for Tamil Nadu.

With TAPS, this figure is projected to rise further, leaving barely one-third of revenue for infrastructure, welfare, healthcare, education, and that too before accounting for corruption leakages, commissions, and freebies.

Notably, Tamil Nadu has already reached a point where borrowing is required to meet salary obligations. TAPS adds a permanent, escalating liability to this equation.

Former Union Finance Minister P Chidambaram, hardly a DMK critic, admits the scheme is viable only if the government exercises “sound fiscal discipline” and substantially improves own-tax revenue.

In other words, even those defending the scheme implicitly acknowledge it is a heavy long-term obligation strapped onto a debt-loaded state.

Who Really Benefits – And Who Pays?

The DMK’s messaging frames this as justice for “long-suffering” government employees. Unions that had been agitating against CPS for nearly two decades have indeed welcomed TAPS, calling off protests and strikes after the announcement.

But look at the distributional reality:

Tamil Nadu’s population is roughly 8-8.5 crore.

State government employees (including various cadres) are in the low‑to‑mid teens of lakhs; even if one takes 14–15 lakh as a rough estimate, they form about 2% of the population.

Committed expenditure on salaries and pensions already takes up well over 60% of revenue receipts, and interest payments consume another substantial slice.

TAPS is therefore structurally designed to lock in more of the state’s limited fiscal space for a small, organised segment that can bargain, strike and vote as a bloc. The unorganised 98% – farmers, small traders, informal workers, the urban poor – are left to compete for whatever remains after salaries, pensions, interest, and political freebies are paid.

The DMK knows precisely what it is buying – Each government employee represents not just one vote but a family cluster, easily expanding into tens of lakhs of reliable votes when spouses and dependents are included.

In a state where tight margins and alliance arithmetic decide power, guaranteeing lifetime benefits to this cluster is electoral insurance dressed up as social justice.

Welfare Or Weaponised Vote-Bank Politics?

The timing is not accidental. The scheme appears just before the 2026 Assembly elections, after years of employee unrest over CPS. In a context where the DMK is already under pressure on issues like inflation, corruption allegations, and anti-incumbency.

This move can be seen as the DMK “soothing employees with a new pension scheme ahead of polls” and “launching TAPS in an election year” to tap government staff as a dependable support base.

This is merely a “vote bank scheme” that entrenches government employees and their families as a permanent DMK-aligned constituency and a “deceptive OPS”, because while it promises 50% pension, it keeps employees contributing and leaves crucial operational details to future G.Os – which any future government can dilute, delay or litigate.

Once again, the pattern is familiar: large, headline-grabbing promises targeted at a specific organised group, with the fiscal pain deferred and diffused across the general taxpayer base over decades.

Framed bluntly, for government employees, TAPS is a windfall; for Tamil Nadu’s finances, it is a tightening noose; for the average citizen outside the Sarkari ecosystem, it is yet another hidden tax on their future, imposed in the name of “Dravidian welfare”.

Whether voters see through this layered packaging in 2026 – or reward the DMK for delivering high-end guarantees to a small segment while preaching social justice to the rest – will decide if schemes like TAPS become the new normal in state politics.

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.