A 34‑year‑old man named Suraj had come from Odisha to make a living in Tamil Nadu. On that day, he was just minding his own business travelling in a local train. Enter a bunch of 17-year-old uncouth, deracinated, drug addict ‘Pullingos’ brandishing machete. One of them was harassing the Odisha man who doesn’t even know the language and what these guys are high on. Another fellow is shooting a video to upload it on Instagram. Suraj avoids them and goes about his work but he’s dragged away, and hacked in a deserted spot while the attack was filmed like entertainment content.

These four school‑age boys did not wake up one morning and suddenly invent this grammar of violence. They brandished a weapon on an EMU train, using a sickle as a prop to shoot “reels”. Stalked the victim after he got down, dragged him to an isolated area, brutally assaulted him, and filmed it like a set piece.

It is an indictment of a cultural ecosystem that has normalised blood, blades, and intoxication as “style.”

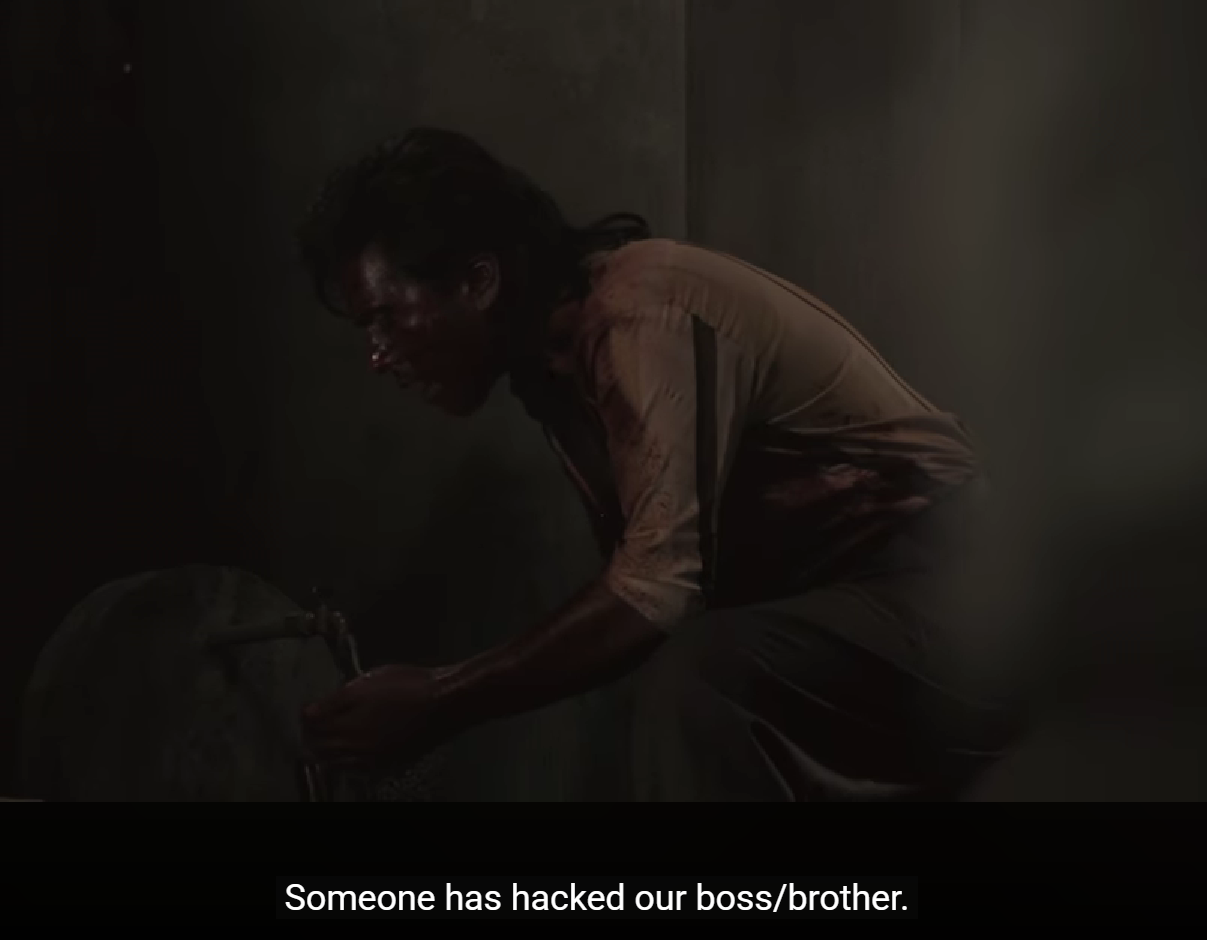

This is exactly the visual language that much of present‑day Tamil cinema (Dravidiawood) has been peddling: slow‑motion swagger with machetes, “mass” entries bathed in blood, and violence cut and packaged like a music video. When teenagers consume hundreds of hours of such content, the line between performance and reality begins to blur.

Dravidiawood’s Blood‑Soaked Aesthetic

Look at Tamil posters and trailers of the last few years – Guns, sickles, splashes of blood – “first look” itself is a riot of gore.

This is the poster of a film featuring the much-hyped director Lokesh Kanagaraj who is known for glorifying drugs and violence in his films.

Far from showing any restraint, Kanagaraj has been unapologetic when confronted about this portrayal, bluntly stating that there will be “no compromise on violence” in his films.

Lokesh Kanagaraj’s filmography follows a strikingly consistent pattern: the centrality of the drug trade, the normalisation of extreme violence, and the aestheticisation of gun and machete culture. This is not incidental storytelling—it is the spine of his so-called cinematic universe.

In Leo, the infamous café massacre and the relentless use of guns and bladed weapons turn extreme violence into a visual flex, framing brutality as an extension of the hero’s charisma.

In Vikram, the character of Rolex (played by Suriya) is elevated into a near-mythic figure—a blood-thirsty criminal whose savagery is stylised, glorified, and cheered, reducing mass murder to a moment of cinematic celebration.

In this ‘cinematic universe’, gore is currency, criminality is cool, and violence is stripped of consequence and repackaged as mass entertainment.

Dravidiawood films are packed with drug trafficking, bootlegging, hacking sequences, and obscenity, with every other line an abuse and every other scene an excuse to show someone being butchered.

After two and a half hours of glorified mayhem, a line about “drug free society” or “say no to violence” is tossed in at the end as a fig leaf.

Take another much-hyped and celebrated director, Vetrimaaran. In the Arasan trailer, Simbu is repeatedly projected as a blood-soaked figure, brandishing a sickle—rage, gore, and intimidation packaged as heroism. The imagery leaves little to the imagination: violence is not incidental, it is the selling point.’

Or consider Vada Chennai, where organised crime and contract killers are not merely depicted but glorified. Rowdies who murder for a living are framed as layered, heroic protagonists, their brutality aestheticised and justified through backstories rather than questioned. The moral line is not blurred—it is erased altogether.

The so-called “Super Star” Rajinikanth is no exception. In Jailer, directed by Nelson, the film elevates him as a mass hero at the very moment he shoves a knife down a man’s throat in front of his own family, converting an act of cold-blooded brutality.

This is not accidental. Many directors and stars are deliberately making these films as a profitable formula. When questioned, they shift the blame onto “the audience”: “People like it, so we are only giving what they want.” That is cowardice dressed up as market logic.

Heroes As Upgraded Villains

Once, villains alone smoked, drank, and hacked people to pieces. Today the hero himself does what yesterday’s villain did – deals with gangsters, drinks openly, mouths obscenities, and slashes enemies in lovingly choreographed scenes.

Films that tried to move away from this – the so‑called “thug life” or “coolie” experiments that did not romanticise criminals – were dismissed as flops, and the industry ran straight back to the gangster template.

Tamil and other “gangster” films are steadily turning a section of Gen Z into violence‑worshipping clowns and budding monsters. The message is simple: to be “mass”, you must be merciless; to be “cool”, you must be high.

There is also a cruel class divide at work. Cinematic violence is consumed as “mass entertainment” by audiences who will never face its consequences. But its fallout is borne by the poorest – migrant workers, daily wagers, outsiders – people like Suraj, who lack protection, influence, or outrage capital. Violence is aestheticised in air-conditioned theatres and executed in slums, railway stations, and dark alleys.

Certain filmmakers have played a defining role in this descent. They have pushed the envelope not for art, but for shock. They have dragged even ageing superstars into blood-drenched narratives so extreme that films once suitable for families now require “A” certificates. Responsibility lies not just with directors, but with stars who lend legitimacy and reach to this violence.

Ask yourselves this: if someone from your own family were chased, hacked, and left bleeding by minors intoxicated on this cinematic fantasy, would you still defend it as “art”? Would you still hide behind box office numbers?

Suraj travelled thousands of kilometres for a livelihood. He now lies scarred, physically and forever emotionally, while his family stares into an uncertain future. For a few thousand rupees a month, he paid with his blood. And yes, those who profit from glorifying violence carry a share of that moral burden.

If the obsession with bloodlust, drugs, and weapons continues, both on screen and among cheering audiences, there is no guarantee that today’s 17-year-olds will not be replaced by 10-year-olds tomorrow. Cinema shapes imagination before law ever intervenes.

We all must introspect. What exactly is the censor board censoring anymore? If minors can replicate on screen what passes certification, then the certification process has collapsed into a rubber stamp. When blood-soaked films sail through with cosmetic cuts, the board is licensing consequences. Filmmakers must stop hiding behind excuses. And an industry that once shaped social reform must ask itself a brutal question: when did it become a factory for rage?

When cinema trains children to enjoy violence, the streets will eventually stage the sequel.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.