Kolathur Mani, the President of Dravidar Viduthalai Kazhagam (DVK), has once again demonstrated his extreme animosity towards Brahmins, pushing his rhetoric to an unacceptable level. This time, he has made a series of unfounded claims, presenting his personal interpretations as historical fact and distorting the truth to an egregious degree. Such actions are deeply troubling.

Individuals like Kolathur Mani, who wants to sustain the Nazi-like Dravidian ideology, often face issues with the accuracy of historical records and existing documents. When crafting their narratives, they position themselves as historians and fabricate stories to persuade their audience. If their accounts encounter gaps or inconsistencies, they frequently attribute these to statements made by historical leaders or obscure references to other books, often citing their own ideologically-driven works as sources.

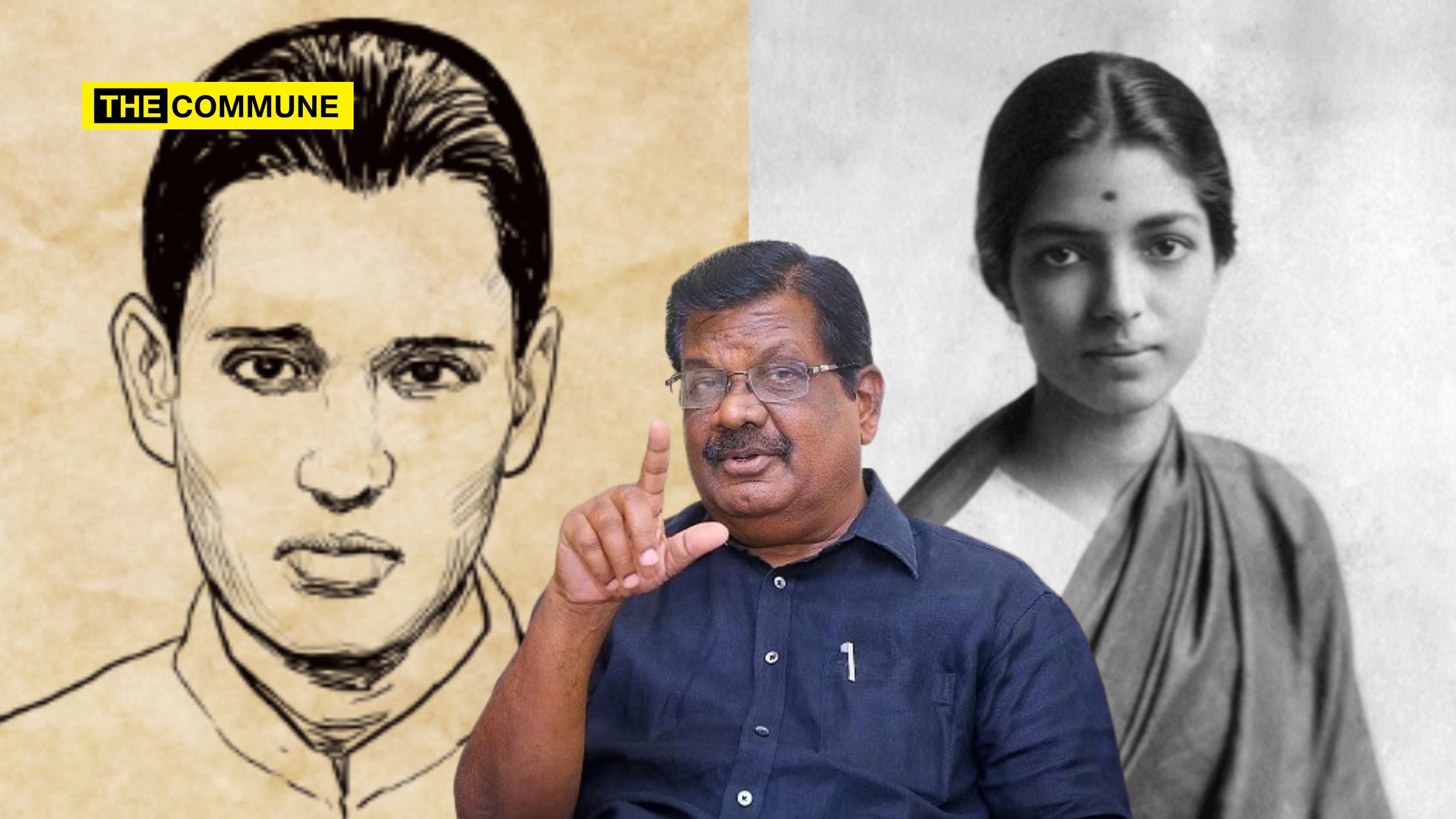

In light of this, it’s crucial to critically examine and dismantle these fabricated narratives one by one. The first instance of distortion in Kolathur Mani’s narrative concerns Rukmini Laxmipathi, an Indian independence activist and politician. Mani disparaged her achievements by suggesting that the only reason a road was named after her was due to her Brahmin caste.

Kolathur Mani narrated, “There is a road called Rukmini Laxmipathi Road in Chennai. She is a great independence activist, but, what she did was sit in the car and distributed the Congress notice, for which the British caught her and filed a case. For giving Congress notice. In this issue she became a martyr and a road has been named for that sacrifice. Whatever the Paapaan (slur word for Brahmins) does they get magnified, while our efforts becomes dismissed.”

Mani’s portrayal is not only inaccurate but also dismissive of Laxmipathi’s genuine contributions. If he had reviewed Tamil Nadu’s history school textbooks, he would have learned that his critique is misplaced. In reality, Rukmini Laxmipathi was a dedicated follower of Gandhi and actively participated in the Salt Satyagraha of 1930 in Vedaranyam, where she was jailed for a year, becoming the first female prisoner in India. She was significantly influenced by leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi, C Rajagopalachari, and Sarojini Naidu.

In 1934, Laxmipathi was elected to the Madras Legislative Council, and three years later, she became the first woman member of the Legislative Assembly. In 1946, she served as the Minister of Health in the Madras Presidency cabinet, marking her as the first female minister in the state. Her contributions to Indian politics and social reform were significant and deserving of the honor of having a road named after her.

In his next narrative, Kolathur Mani turned his attention to another Indian independence activist, Vanchinathan, and propagated the misleading claim that Vanchinathan was motivated by casteism rather than genuine patriotism. Mani suggested that Vanchinathan killed British officer Ashe solely to uphold the caste hierarchy.

Mani cleverly recounted a story he attributed to Iyothee Thass Pandithar’s Tamilan magazine. According to that, Ashe was travelling in a chariot when a woman carrying heavy fodder fell and cried out in labour pain. Ashe, trying to help, ordered the woman be carried in his chariot to the hospital. However, Brahmins supposedly blocked their path, stating low caste people should not cross their street and Ashe had to threaten them with his revolver to gain passage through the Brahmin streets. Mani claimed that this incident led Brahmins to plot the assassination of Ashe.

However, there is no substantial evidence supporting this narrative. Iyothee Thass Pandithar, a prominent scheduled caste leader and an influential figure, ran his magazine from 1907 until his death in 1914, but there is no record of his magazine publishing such a story about the murder of Ashe. Mani further claimed that Vanchinathan’s own suicide note, which purportedly detailed his reasons for shooting Ashe, contained statements about defending Sanatana Dharma. Mani interpreted this to mean that Vanchinathan’s motives were rooted in caste protection rather than the fight for freedom. According to Mani, Vanchinathan’s letter described how the presence of oppressed people on Brahmin streets violated Sanatana Dharma and stated that the killing of George Ashe was a reaction to such violations.

Mani peddled that, “Vanchinathan wrote a letter why I shot Ashe, in that he gives explanation to sanatana dharma what he says, It is against Sanatana Dharma if oppressed people carried through our streets. He has written that we have decide to kill George Panchaman, who eats cow meat and tramples our Sanatana Dharma.”

Mani’s portrayal thus seeks to redefine Vanchinathan’s legacy from that of a freedom fighter to a caste defender, fabricating a narrative that lacks historical corroboration.

The martyrdom of Vanchinathan deserves to be honoured and remembered. Inspired by the Surat Congress of December 1907, VO Chidambaram Pillai, a pioneering figure in Indian shipping, organized political meetings in Tuticorin and Tirunelveli. These meetings were marked by passionate speeches from Subramania Siva, contributing to the spread of the freedom struggle. In February 1908, around 1,000 workers went on strike at the Coral Mills in Tuticorin. The collector, Robert William Escourt Ashe, had imposed Section 144, which restricted the workers’ union activities and was strongly opposed to them.

The situation escalated when patriotic leaders planned to commemorate Bipin Chandra Pal’s release as Swarajya Day, only to face violent repression from the district administration. By March 1908, VOC, Siva, and Padmanabha Iyengar were arrested, and riots erupted in Tuticorin and Tirunelveli, described as acts of incendiarism. Additionally, Ashe’s actions were believed to have contributed to the downfall of VOC’s Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company.

Robert Ashe, born in Ireland in 1872, began his career in India as an Assistant Collector in 1895, eventually rising to the positions of District Magistrate and Collector. By 1907, he was stationed in Tirunelveli and temporarily officiated in Tuticorin, where significant events unfolded. On 17 June 1911, while traveling with his wife, Mary Lillian Patterson, Ashe’s train stopped at Maniyachi. There, a man dressed in traditional attire and another in a dhoti approached the carriage and shot Ashe at point-blank range with a Belgian-made pistol. The assailant then ran to the latrine and committed suicide. He was associated with the Bharatha Matha Association.

In contrast to Kolathur Mani’s claims, the 1918 Rowlatt Committee report, chaired by a judge from the King’s Bench Division of His Majesty’s High Court of Justice, provides a different account. According to the report, “Upon the body of the murderer was found a letter in the Tamil language which stated that every Indian was trying to drive out the English and restore swarajya and the Sanatan Dharma. Rama, Sivaji, Krishna, Guru Govind and Arjum ruled over the land protecting all religion, but now the English were preparing to crown in India George V, a Mlecftlta, who ate the flesh of cows. Three thousand Madrasis had taken a vow to kill George V, as soon as he landed in the country. To make known their intention to others, he, Vanchi, the least in the company, had done that deed that day.”

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.