The ASER 2024 report reveals significant shifts in foundational literacy and numeracy levels across India, highlighting both recoveries and disparities in educational outcomes post-pandemic. The data underscores substantial progress in some states, particularly in regions that historically lagged behind, such as Uttar Pradesh, which showed remarkable improvement despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic. However, Tamil Nadu, often heralded for its educational advancements, has fallen behind, especially in government school performance.

Despite numerous claims by DMK ministers since 2021 that their efforts have greatly improved access to education, the current statistics stand in stark contrast, exposing the truth behind those boasts. Despite receiving funding from the central government and state allocations, Tamil Nadu continues to lag behind Uttar Pradesh in both arithmetic and reading abilities. Notably, Uttar Pradesh, once considered a weak performer in education, has made remarkable strides, while Tamil Nadu, traditionally regarded as a pioneer in educational reforms, now faces severe setbacks in government school education, a sector overseen by the DMK government.

Comparative Study – Uttar Pradesh Vs Tamil Nadu

Unfortunately, while northern states that historically lagged in educational performance have shown significant improvement, Tamil Nadu, governed under the Dravidian model, lags behind. Despite claims of being a leader in education, with the ruling government often crediting Dravidian ideologue E.V. Ramasamy Naicker for advancing Tamil education, the state still falls behind places like Uttar Pradesh in terms of progress.

Reading Skills

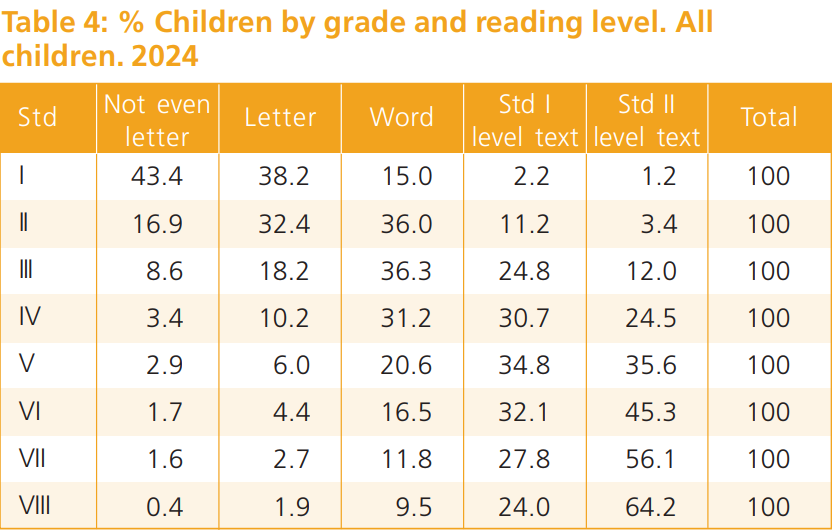

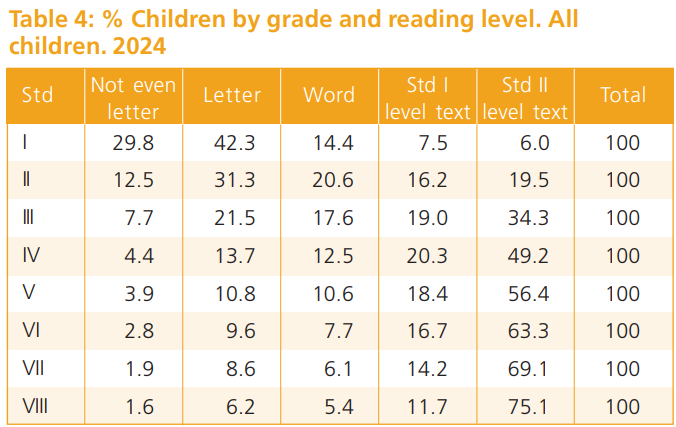

When comparing the literacy levels of children in Standard III between Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh in 2024, Uttar Pradesh appears to have made more progress, especially in terms of children able to read at the Standard II level. In Tamil Nadu, 8.6% of children cannot even read letters, 18.2% can read letters but not words or higher, 36.3% can read words but not Standard I level text, 24.8% can read Standard I level text but not Standard II level text, and only 12% can read Standard II level text. In contrast, Uttar Pradesh shows better results: 7.7% of children cannot read letters, 21.5% can read letters but not words or higher, 17.6% can read words but not Standard I level text, 19% can read Standard I level text but not Standard II level text, and 34.3% can read Standard II level text. Despite both states facing challenges, Uttar Pradesh stands out with a significantly higher percentage of children able to read at the Standard II level, indicating that it has made greater strides in improving foundational literacy compared to Tamil Nadu, which has traditionally been seen as a leader in education but still has a considerable portion of children struggling with basic reading skills.

What is particularly concerning in Tamil Nadu, according to the survey, is that 45.3% of children in Class VI, 56.1% in Class VII, and 64.2% in Class VIII can only read at a Standard II level but are unable to read above that level.

(ASER – Tamil Nadu)

(ASER – Uttar Pradesh)

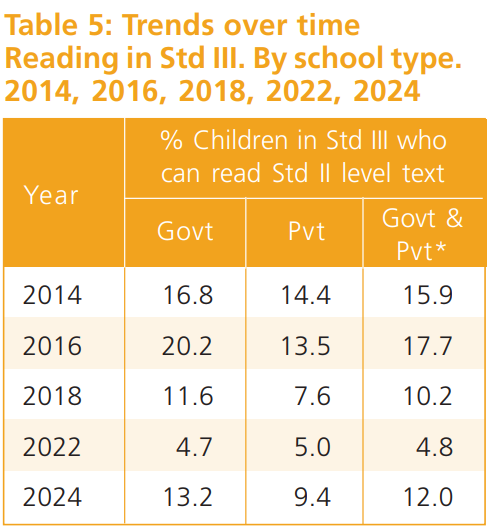

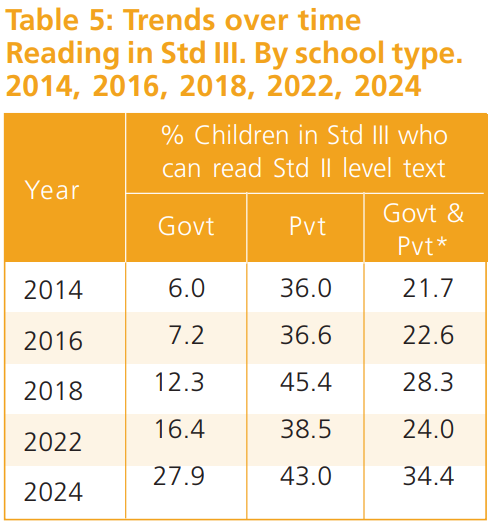

In the long-term progressiveness in tend analysis of maintaining the reading ability, the percentage of children in Standard III in Tamil Nadu who can read at a Standard II level text showed a concerning trend. In 2014, it was at 16.8%, and it slightly improved to 20.2% in 2016. However, there was a sharp decline to just 2.2% in 2022, likely due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Despite Tamil Nadu’s claims of implementing schemes like Illam Thedi Kalvi to improve foundational literacy, the state could not even reach the 2014 level, despite spending public funds.

(ASER – Tamil Nadu)

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh, which had only 6% of children who can read Standard II level in 2014, managed to maintain a 16.4% level in 2022, even during the pandemic. By 2024, Uttar Pradesh saw a significant improvement, reaching 27.9%, showing consistent progress in literacy levels.

(ASER – Uttar Pradesh)

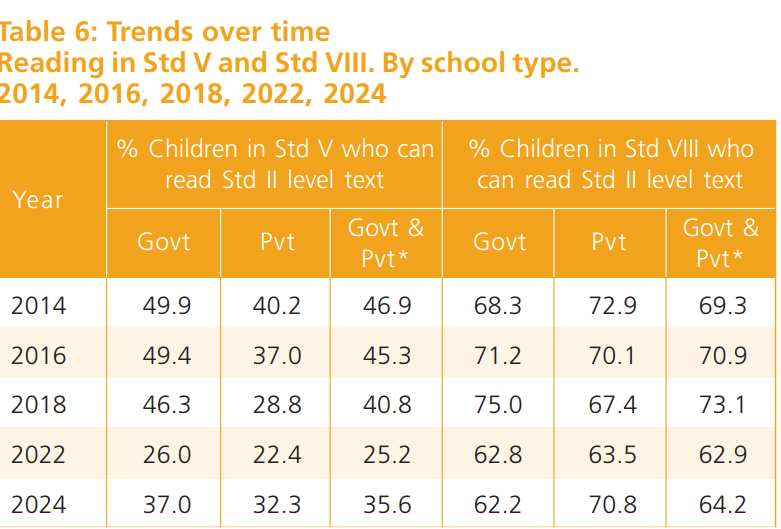

Similarly, the ASER 2024 report highlights significant gaps in Tamil Nadu, with the percentage of children in Standard V and Standard VIII who can read at a Standard II level dropping to new lows. This suggests that despite the Dravidian model government announcing schemes for government schools during the pandemic, there was little to no tangible impact on the ground, and no real improvement in the performance of government school students.

Arithmetic Ability

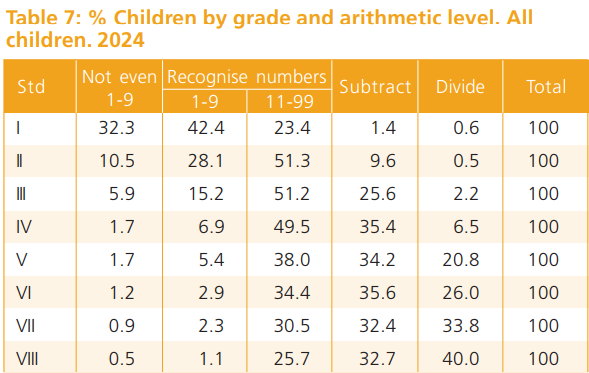

In Tamil Nadu, the performance of children in Standard III shows concerning gaps in arithmetic skills. Among these children, 5.9% cannot even recognize numbers from 1 to 9, while 15.2% can recognize numbers up to 9 but cannot recognize numbers up to 99 or higher. Additionally, 51.2% can recognize numbers up to 99 but are unable to perform subtraction, 25.6% can do subtraction but cannot perform division, and only 2.2% can do division.

(ASER – Tamil Nadu)

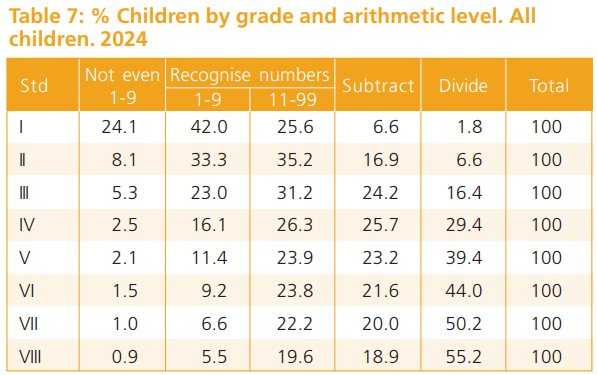

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh’s performance shows slightly better results. Among Standard III children, 5.3% cannot recognize numbers from 1 to 9, but 23% can recognize numbers up to 9 but cannot recognize numbers up to 99. A smaller proportion, 31.2%, can recognize numbers up to 99 but cannot perform subtraction, while 24.2% can do subtraction but cannot perform division. Notably, 16.4% of children in Uttar Pradesh can perform division, a significantly higher percentage than in Tamil Nadu.

(ASER – Uttar Pradesh)

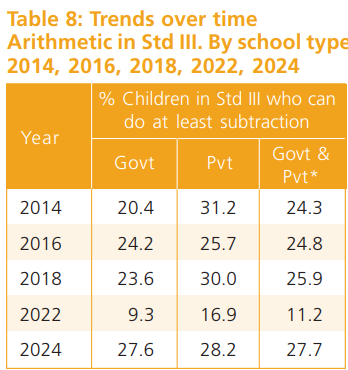

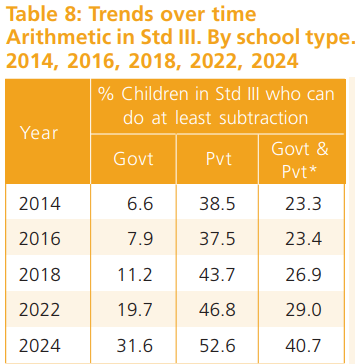

The trend analysis of the percentage of children in Standard III who can perform at least subtraction from 2014 to 2024 shows a fluctuating pattern in government schools in Tamil Nadu. In 2014, only 20.4% of children were able to do subtraction, which slightly improved to 24.2% in 2016, then dropped to 23.6% in 2018. A sharp decline was seen in 2022, with only 9.3% of children being able to do subtraction, likely due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, by 2024, the figure rose to 27.6%.

(ASER – Tamil Nadu)

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh, which lagged behind Tamil Nadu in 2014 with just 6%, showed significant improvement over the years. The state rose to 7.9% in 2016, 11.2% in 2018, and despite the pandemic, it maintained 19.7% in 2022. Remarkably, by 2024, Uttar Pradesh reached 31.6%, surpassing Tamil Nadu’s performance since 2022. This shows that Uttar Pradesh’s progress has been consistently stronger, even outpacing Tamil Nadu in recent years.

(ASER – Uttar Pradesh)

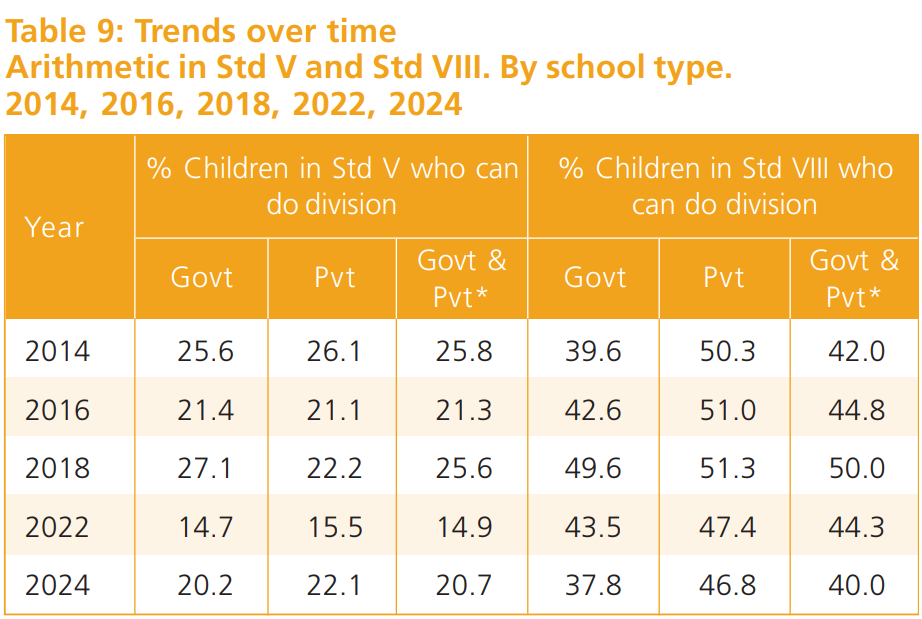

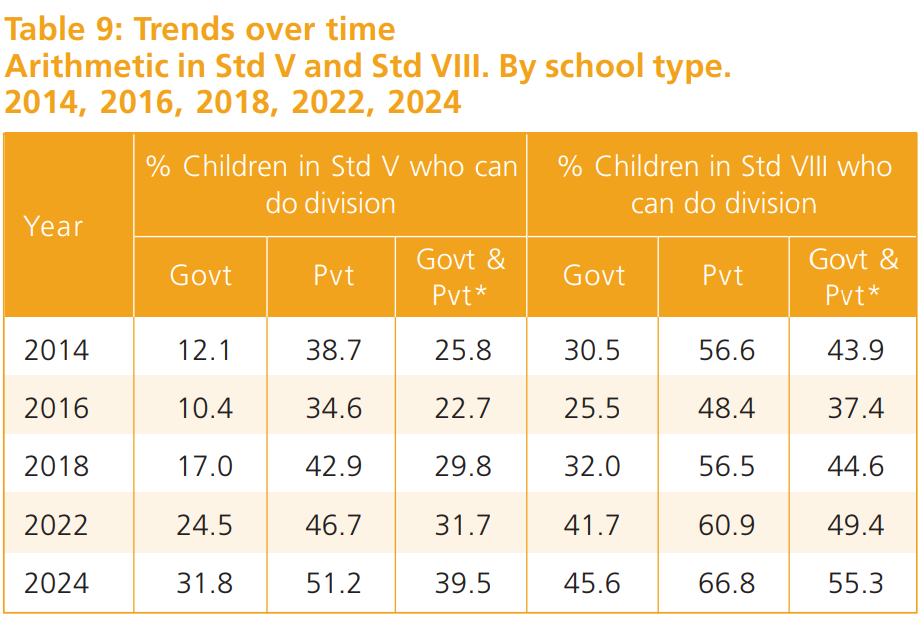

Looking at the trend over time for the percentage of children in Standard V and Standard VIII who can perform division from 2014 to 2024, we see a contrasting performance between Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. In Standard V, Tamil Nadu had 25.6% of children able to do division in 2014, but this figure dropped to 20.2% in 2024. On the other hand, Uttar Pradesh showed significant improvement, rising from 12.1% in 2014 to 31.8% in 2024.

For Standard VIII, Tamil Nadu saw a decline in division skills, with 39.6% of children able to perform division in 2014, which decreased to 37.8% in 2024.

In contrast, Uttar Pradesh made a notable leap from 30.5% in 2014 to 45.6% in 2024, surpassing both its own previous performance and that of Tamil Nadu in terms of arithmetic ability.

In conclusion, as the old moral story suggests, a donkey worn out becoming an ant symbolizes a struggle for identity and purpose. Similarly, Tamil Nadu has become a state that seems to lack genuine interest in supporting government school students, especially those from marginalized backgrounds who rely solely on government-provided education. Despite the Dravidian model government’s claims of EVR’s legacy in shaping the state’s educational foundation, the data paints a different picture. Poor-performing states have now outperformed Tamil Nadu, leaving the claims of progress looking more like a mockery.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.