“Brahmins had 100% reservation for 3000 years”, says Dr Vikas Divyakirti, echoing a common Dalit‑Bahujan criticism that for millennia, scriptural and social norms gave Brahmins a near‑total monopoly over education and “merit.”

“Brahmins had 100% reservation for 3000 years,” says Dr Vikas Divyakirti.

One sentence. Distortion with intent. A shortcut to turning one community into the villain of every era.@sangamtalks pic.twitter.com/PDGpm8kAJO— Hindu Network Foundation (@hindufund_) February 5, 2026

It is an effective rhetorical device, but it is also, in this exact form, a distortion with intent, a shortcut that risks turning one community into the villain of every era, regardless of what the historical data in specific regions and centuries actually show.

In this article, we examine the colonial‑era educational surveys of William Adam in Bengal and Bihar, along with data from the Madras Presidency, to test the claim that “Brahminical Hindus” systematically denied education to so-called “lower castes”.

William Adam’s Surveys: Who Went To School In 1830s Bengal & Bihar?

In the 1820s, Scottish Baptist missionary William Adam arrived in Bengal to preach and “harvest heathen souls.” By the mid‑1830s, the British Governor‑General William Bentinck commissioned him to conduct an official survey of vernacular education in the “native schools” of Bengal and Bihar. Between 1835 and 1838, Adam submitted three official reports on education.

The schools he documented were indigenous institutions:

- Run locally by Hindus in villages.

- Funded by parents or village committees.

- Taught in native languages like Bengali and Hindi.

- Not operated or administered by the East India Company.

- Distinct from the missionary schools, which were set up and run separately by Christian missions.

Adam’s data, taken at face value, seems to disprove the narrative that forward caste Hindus, especially Brahmins, monopolised education and excluded so-called lower castes. His caste‑wise breakdown from districts like Burdwan and South Behar shows that Shudra and socially disadvantaged castes not only had access to education in native schools, but in many places formed the majority of the student body.

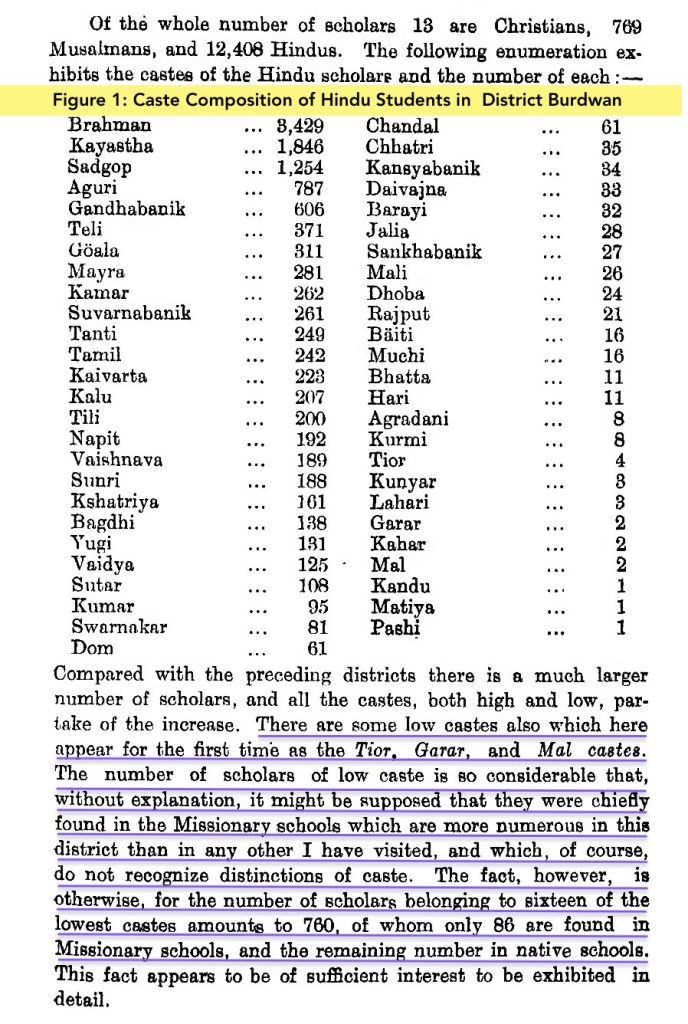

Burdwan District: So-Called ‘Shudras’ Dominate Enrolment

In Burdwan district, Adam counted 12,408 Hindu students in native schools. The caste composition was roughly as follows:

- Brahmins: about 3,429 students, or 27.6% of the student body.

- Other Castes (Kayasthas, Vaidyas, Kshatriyas): 2,132 students, or 17.2% (Kayastha 1,846; Vaidya 125; Kshatriya 161).

- Shudras: 6,087 students, which you correctly identify as about 49% of the total. Castes here included Sadgop, Aguri, Gandhabanik, Teli, Goala, Mayra, Kamar, Suvarnabanik, Tanti, Tamil, Kaivarta, Kalu, Tili, Napit, Vaishnava, Sunri, Sutar, Kumar, Swarnakar, Rajput, Mali, Kurmi, and others.

- Avarnas: 760 students, or 6.1% of the total, drawn from Chandals, Doms, Muchis, Haris, Bagdhi, Dhobas, Jalias, Tiors, Garars, Mals, Pashis, and others.

In other words:

- Brahmins + Other Castes: about 44.8%.

- Shudras + Avarnas: about 55%, making them the majority of Hindu students in Burdwan’s native schools.

Dharampal’s and later analyses of Adam’s tables emphasise the same point: “the elementary school students present an even greater variety and it seems as if every caste group is represented in the student population, the Brahmins and Kayasthas nowhere forming more than 40% of the total.”

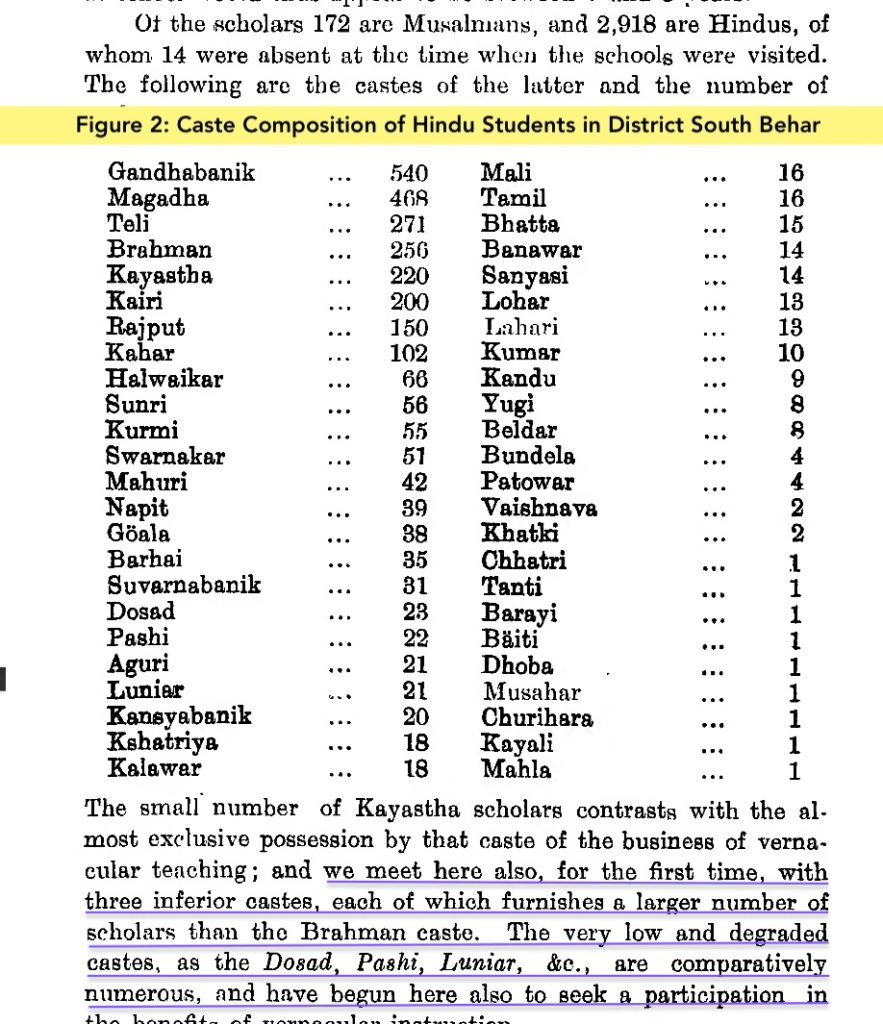

South Behar: So-Called ‘Shudras’ Form Over Four‑Fifths Of Hindu students

In South Behar, the picture is even more lopsided in favour of Shudra students. Adam’s tables show that Brahmins and other castes together were less than 17% of enrolled Hindu students:

- Brahmins: about 250 students (≈ 8.6%).

- Other Castes (Kayastha 220; Kshatriya 18): 238 students (≈ 8.1%).

- Shudras: 2,364 students, about 81% of the student body. These included Gandhabaniks, Magadhas, Telis, Kairis, Rajputs, Kahars, Halwaikars, Sunris, Kurmis, Swarnakars, Mahuris, Napits, Goalas, Malis, Tamils, Lohars, Laharis, Kumhars, Kandus, Yugis, Beldars, Bundelas, Patowars, Vaishnavas, Khatkis, Barhais, Suvarnabaniks, Aguris, Kansyabaniks, Kalawars, and others.

- Avarnas: 66 students, or 2.3%, explicitly classified by Adam as “very low castes” (Dosad, Pashi, Luniar, etc.).

Again, the headline is unmistakable:

- Brahmin + Other Castes: ≈ 16.7%.

- Shudras: ≈ 81%.

- Avarnas: ≈ 2.3%.

This is the exact opposite of the claim of “100% Brahmin reservation” in schooling; Shudra groups overwhelmingly outnumbered other forward castes in Adam’s data for native schools in this district.

Adam’s Own Conclusion: “All The Castes, Both High And Low, Partake Of The Increase”

Adam did not just give tables; he offered qualitative commentary. In summarising his findings across districts, he emphasised that:

- All castes, high and low, were present in the schools.

- Even communities regarded as very low, such as Tior, Garar, Mal, appear in the enrolment lists.

- In districts like Beerbhoom and Burdwan, vernacular schooling had undergone “a social change, partaking of the nature of a moral and intellectual discipline,” reducing prejudices and allowing children from different castes and even religions to study together.

He also notes that in the Beerbhoom and Burdwan districts there were 1,001 Muslim scholars in Bengali schools, and in South Behar and Tirhoot there were 177 Muslim scholars in Hindi schools, studying alongside Hindus. Teachers from Hindu and Muslim communities taught mixed classes, where students “of the different castes” and religions learnt together in the same schoolhouse.

This directly undercuts the idea that “Brahminical Hindu” village schools were structurally designed to block so-called lower castes from learning.

Missionary Vs. Native Schools: Where Did Avarna Children Actually Study?

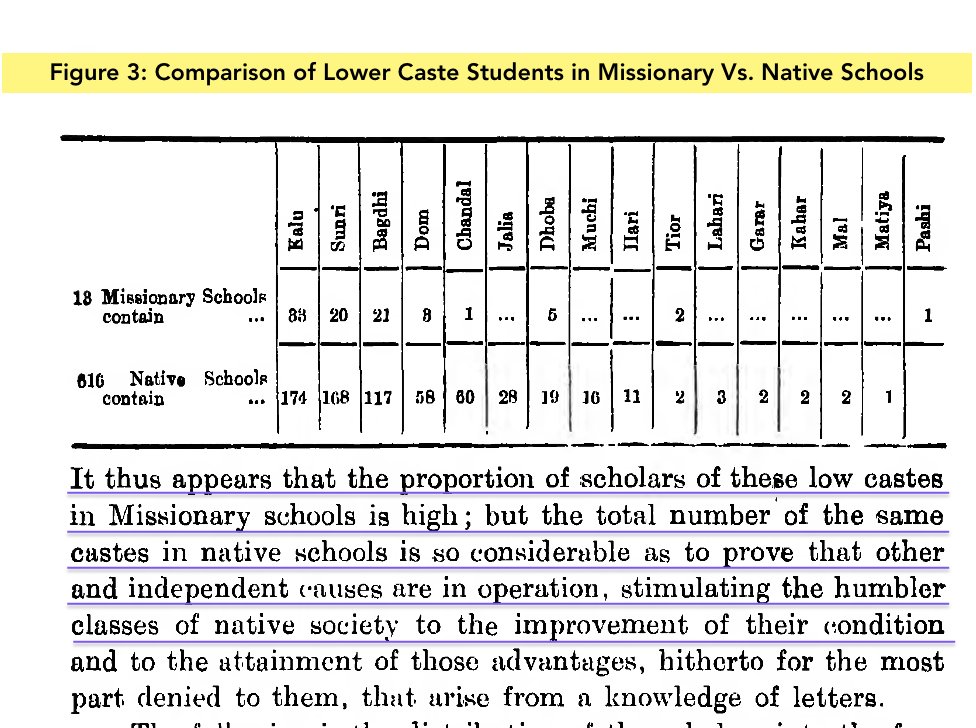

Adam’s comparison of missionary schools with native Hindu schools produces another surprise.

- Out of 760 students from the lowest castes, only 86 were in missionary schools, while 674 were in native schools.

- Adam remarks that the “so considerable” number of low‑caste students in native schools proves that these institutions were already encouraging “the humbler classes” to seek education, without the need for missionary intervention.

That is, the Avarna participation rate was actually higher in indigenous village schools than in Christian missionary schools in the districts he studied.

This does not make missionary work irrelevant, but it challenges the myth that only Christian missions opened the school gates to other castes, while Hindu village schools operated as exclusive Brahmin enclaves.

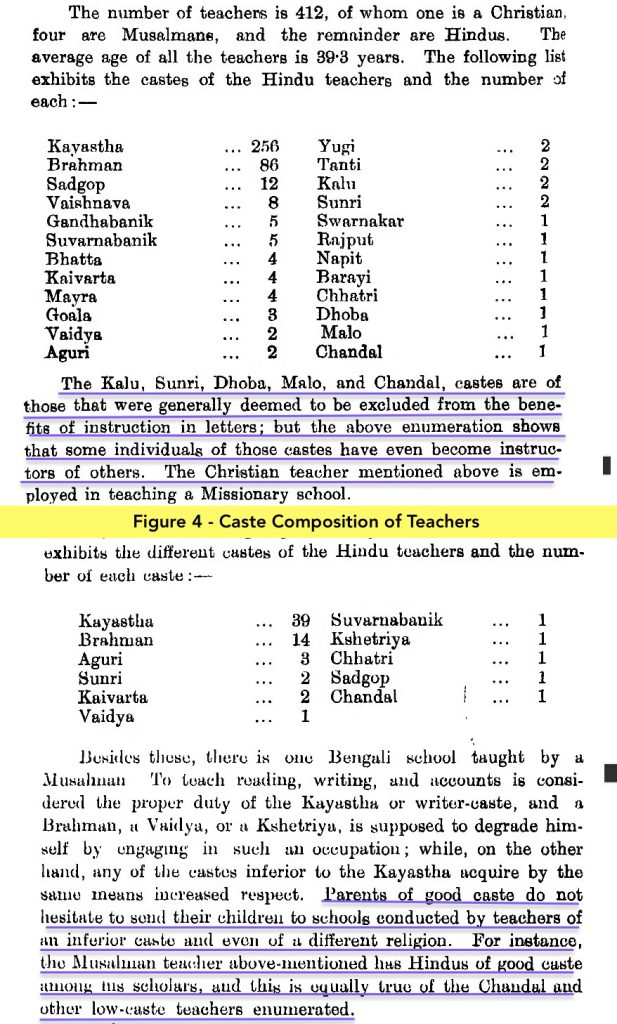

Caste Of Teachers: Other Caste Instructors In “Brahminical” Institutions

Even more counter‑intuitive for the standard story is Adam’s data on the caste composition of teachers. In his tables for certain districts:

- Brahmins and Kayasthas formed a significant share of teachers, especially in higher Sanskritic institutions.

- Yet there were also schoolteachers from pther castes such as Sunri, Kalu, Dhoba, Bagdhi, and even Chandal – groups that later colonial and missionary narratives often portrayed as entirely excluded from literacy.

Adam notes that Hindu parents of “good caste” did not hesitate to send their children to schools taught by teachers of inferior castes or even of a different religion. That is a direct observation from the 1830s, not a retrospective apologetic.

At the same time, when he looks specifically at Sanskritic learning – grammar, logic, law, literature, Vedanta, tantra, etc., he finds that nearly all teachers in those advanced institutions are Brahmins, and the scholars there are much more skewed towards other castes. So:

- Vernacular primary education looks socially inclusive and broad‑based.

- Higher Sanskritic scholarship is much more Brahmin‑dominated.

This nuance is important: there was clear stratification at the level of advanced scriptural learning, but the “100% Brahmin reservation” claim does not apply even to basic village schooling in these districts.

Colonial Myth‑Making: Why the Data were Ignored

Despite Adam’s own numbers, colonial administrators and missionary authors often portrayed Hindu society as so rigidly caste‑bound that so-called ‘lower castes’ were systematically denied education. This narrative served several political purposes:

- Justifying British “civilising” interventions in education and social reform.

- Providing moral cover for missionary expansion and conversion efforts, especially among other castes.

- Supporting the image of the colonial state as a benevolent corrective to “Brahminical oppression.”

Dharampal and other historians argue that Adam’s reports, if taken seriously, undermined a central pillar of this colonial justification namely, the claim that “Brahminical” native schools categorically excluded other castes. The British continued to lean on the stereotype rather than the data.

Madras Presidency: A Similar Pattern Down South

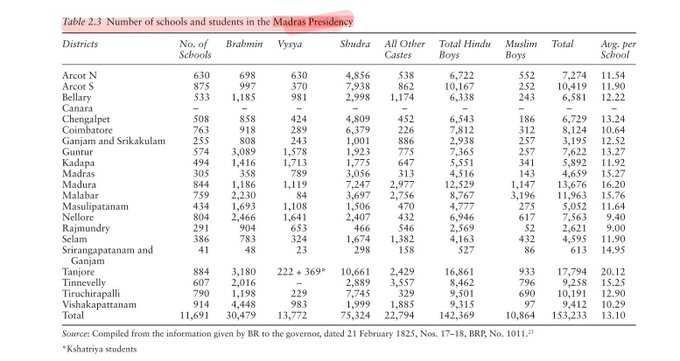

The pattern in southern India also disproves the “100% Brahmin reservation” narrative. Collector reports from the 1820s, later compiled and discussed by historians like Dharampal, show that in the Madras Presidency:

- Out of around 30,211 male school students (in one set of returns), roughly

- 20% were Brahmins and Kshatriyas,

- 9% were Vaishyas,

- 50% were Shudras,

- 6% were Muslims, and

- About 15% were “others”.

A widely circulated summary of 1825 data for the Presidency states that of 11,691 schools and 1.42 lakh Hindu students, 78.5% were non‑Brahmins, while the remaining share were Brahmins and allied castes.

As per this data, 78.5% of the 1.42 lakh Hindu students in 1825 Madras Presidency were non‑Brahmins and this indicates that Shudras and other non‑Brahmin castes formed the vast majority of Hindu students.

As in Bengal/Bihar, this does not mean caste hierarchies were absent or benign. It does show, however, that basic schooling was not reserved entirely for Brahmins even in early 19th‑century south India; socially disadvantaged caste enrolment was substantial, often dominant.

This data, thus shows, that in the 1820s–1830s, in specific regions of Bengal, Bihar, and the Madras Presidency, vernacular village schooling was socially broad‑based, with Shudras and socially disadvantaged castes often forming a majority of students.

It also shows that while some teachers came from socially disadvantaged castes, higher‑caste parents accepted such teachers for their children.

Why The “100% Brahmin Reservation For 3000 Years” Slogan Is Wrong

Within this historical nuance, the line “Brahmins had 100% reservation for 3000 years” collapses a deeply uneven history into a moral absolutism. It does three problematic things:

Temporal overreach: It treats three millennia of evolving social, political, and regional structures as if they were one monolithic Brahmin project, ignoring wide variations across time and space.

Empirical overstatement: In light of Adam’s 19th‑century surveys and Madras Presidency data, it is empirically false to say Brahmins had “100%” of educational seats, even in the last 200 years before modern reservation.

Collective demonisation: It frames an entire community as the permanent villain whose alleged total monopoly must now be “compensated” by policy, which encourages resentment and essentialising rather than accurate, targeted redress.

Colonial narratives about “Brahminical Hindus” running casteist schools were politically convenient for the British and missionaries, even when their own data (Adam’s reports) pointed to a much more mixed reality.

If we uncritically adopt those narratives today, an entire community is penalised and legal entitlements are designed on the basis of debunked or oversimplified stories.

If the goal is just reparative justice, we need morally serious, historically honest arguments, not slogans that flatten centuries of complex social reality into a single accusatory line.

(This article is based on an X Thread By Mumukshu Savitri)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.