In contemporary discourse, especially among certain Dalit activists and progressives, there is often a widespread claim that the Indian Constitution, crafted under Dr BR Ambedkar’s leadership, provides more power and equality to women than Manusmriti, the ancient Hindu text. This narrative, however, is steeped in ignorance, ignoring Dr. Ambedkar’s nuanced views on Manusmriti and its influence on his legal framework for India. It is essential to revisit Ambedkar’s own words and actions to understand the true role of Manusmriti in shaping modern Indian law, particularly on women’s rights.

Ambedkar’s Praise For Manusmriti

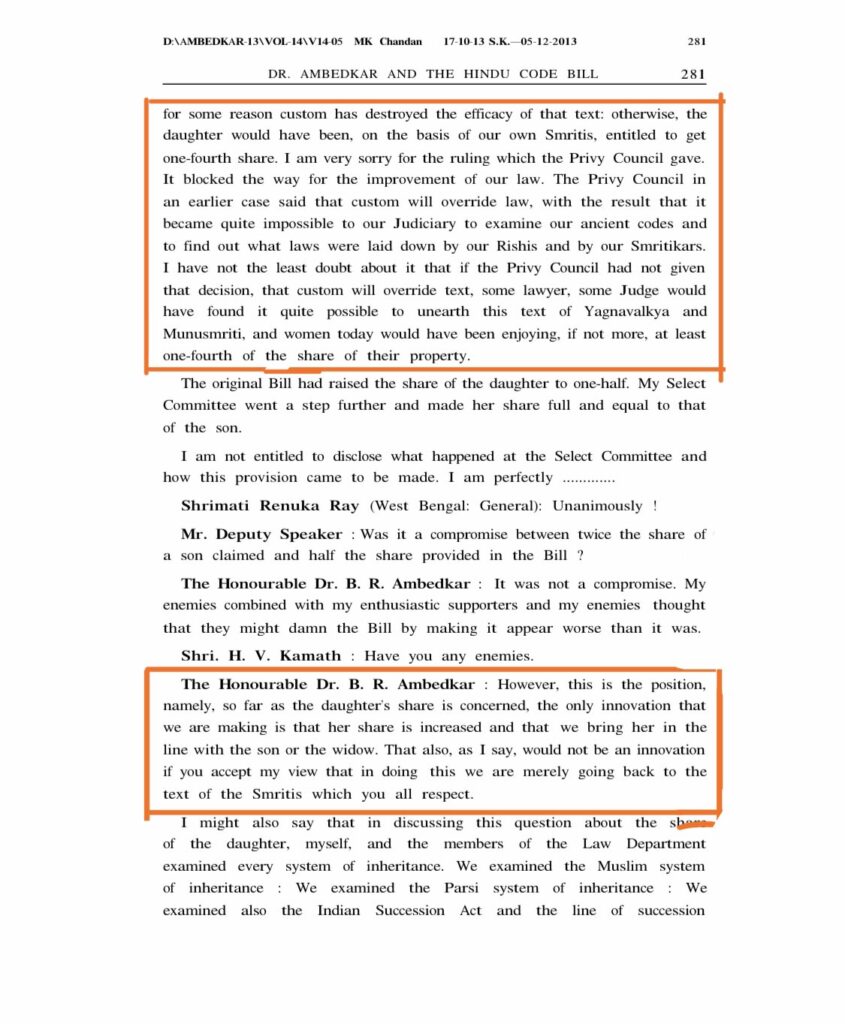

Contrary to the blanket condemnation of Manusmriti by modern critics, including some Dalit activists who argue that it represents the oppression of women and lower castes, Dr. Ambedkar himself recognized the wisdom contained in this ancient text. In his speech to the Constituent Assembly on 24 February 1949, Ambedkar explicitly acknowledged the importance of Manusmriti among other Smritis (texts on Hindu law). He remarked, “Among the 137 Smritis, Yajnavalkya and Manu are of a higher standard.” Ambedkar went on to highlight how Manu’s code provided for women’s inheritance rights, noting that Manu explicitly states that daughters are entitled to one-fourth of the inheritance (Manusmriti, Chapter 9, Shloka 117).

Dr. Ambedkar stressed that the change he was making through the Hindu Code Bill was not an innovation, but rather a return to the original intent of these texts, “We are simply going back to the text of the Smritis which you all respect.” His words were a direct challenge to those who opposed the reforms, particularly critics who claimed the Hindu Code Bill abandoned Hindu scriptures.

Ambedkar’s Use Of Manusmriti In Hindu Code Bill

In fact, Ambedkar used Manusmriti and other Smritis as references when drafting the Hindu Code Bill, which sought to modernize Hindu personal law and grant greater rights to women, including in areas such as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In his speech at Siddharth College on January 11, 1950, Ambedkar elaborated on his use of ancient texts in his reform work, saying, “I used Manusmriti for caste determination, Parashara Smriti for divorce, Brihaspati Smriti for women’s rights, and Manusmriti for inheritance rights.”

This is critical to understanding Ambedkar’s approach. Rather than dismissing the ancient texts wholesale, he extracted relevant and progressive provisions and used them to shape a more equitable legal framework. This was especially important in the context of women’s rights, as Ambedkar believed that the Manusmriti’s provisions on inheritance, particularly those that recognized daughters’ entitlement to a share of property, were far ahead of their time. It is clear that Ambedkar did not see Manusmriti as a monolithic text of oppression, but rather as a source of ideas that could be adapted to modern needs.

The Manusmriti Myth And Modern Misinterpretations

Critics of Manusmriti, particularly those who have not studied the text in detail, often point to certain sections that they claim reflect the oppression of women and lower castes. However, they ignore the broader context and the teachings of Manusmriti on social equality, respect, and justice. It is important to note that Manu himself was a Kshatriya, not a Brahmin, which discredits the notion of Manusmriti being solely a tool of “Brahminical oppression.”

For example, Manu’s code includes provisions that were more progressive than many critics acknowledge. The text states that an elderly Shudra (a member of the lowest caste) should be respected by kings and Brahmins alike, a principle that upholds the dignity of all individuals, irrespective of caste. Moreover, Manu’s varna system was meritocratic, based on actions and deeds rather than birth. A Shudra’s child, if capable, could study the Vedas and rise to the rank of a Brahmin, exemplifying the idea that societal position was not fixed by birth but by merit.

Additionally, the text provides a vision of justice and fairness, including harsher punishments for Brahmins who commit the same crimes as a Shudra, which counters the common narrative of Manusmriti being solely about caste oppression. The document was a governance framework suited to its time, not an eternal law that should be applied unchanged in modern society.

The Misleading Narrative Of “Manu and Oppression”

The ongoing narrative by some activists that Manusmriti inherently oppressed women and lower castes, and that the Constitution of India did far more for women’s empowerment, is fundamentally flawed. This narrative fails to account for Ambedkar’s own engagement with Manusmriti and its provisions for women, which he regarded as progressive for its time.

Dr. Ambedkar, who had earlier burned a copy of Manusmriti in protest against its oppressive aspects, later recognized its contributions to women’s rights, particularly in the area of inheritance. His stance is clear: the Hindu Code Bill was not an abandonment of Hindu traditions but a reformative step to correct the misapplication of these traditions in the modern world.

In his Rajaram Theater speech on 25 December 1952, Ambedkar directly responded to critics of his Hindu Code Bill, stating: “My bill’s critics claim it abandons Hindu scriptures. I challenge them to find a clause unsupported by Manusmriti. Women’s property should go to daughters after death, just as brothers inherit the father’s.”

Dr. Ambedkar’s views on Manusmriti and his use of it to draft the Hindu Code Bill expose the ignorance of those who claim that the Constitution gave women more power than Manusmriti ever did. Ambedkar recognized the positive aspects of Manusmriti, especially its provisions for women’s inheritance rights, and he used those insights to guide his work on legal reforms. The simplistic narrative that dismisses Manusmriti as a tool of oppression ignores the complexity of Ambedkar’s views and the actual content of the text.

Instead of perpetuating misinterpretations and political propaganda, it is crucial to understand the historical context of Manusmriti and Dr. Ambedkar’s nuanced relationship with it. Ambedkar’s engagement with Manusmriti shows that progress is often built upon revisiting and reinterpreting the past, rather than wholesale rejection of it.

This article is based on an X thread by Neha Das.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.