About a week ago, reports indicated that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), promoted by Pakistan as a transformative economic initiative, has failed to achieve its objectives and left the country with a $9.5 billion debt, widely perceived as part of China’s debt-trap strategy.

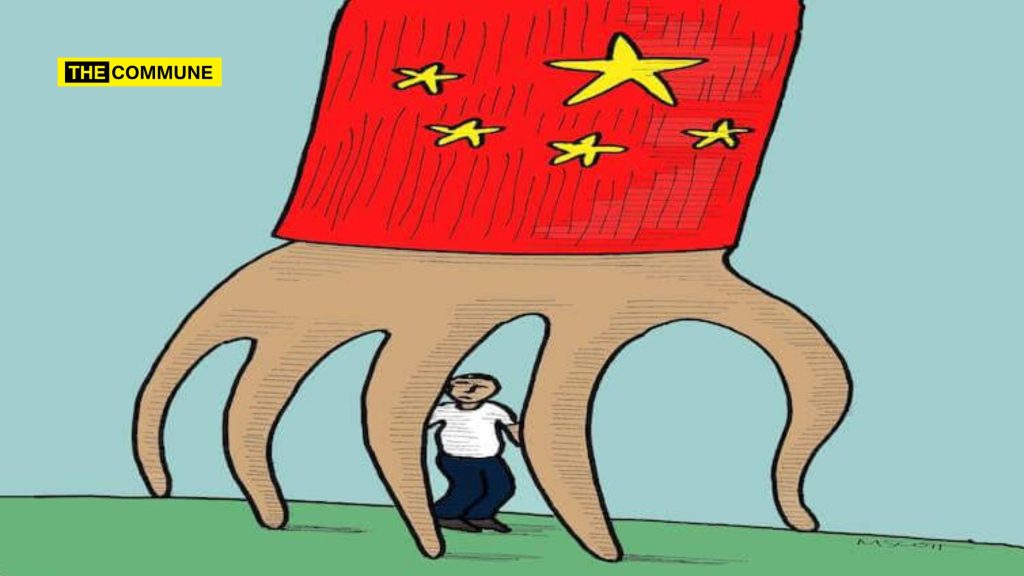

This is not a one-off event. In this report, we examine the growing debt pressures faced by eight developing nations due to extensive borrowing from China, primarily under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). We notice a recurring pattern where large-scale infrastructure and energy projects, financed by Chinese loans, have resulted in unsustainable debt burdens. Many of these projects have failed to generate anticipated economic returns, leaving borrower countries in a cycle of financial dependency. The situation has led to stalled projects, the need for further borrowing or International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailouts and has increased China’s economic and political leverage over these vulnerable nations.

#1 Pakistan’s CPEC Debt Burden

As of 22 September 2025, Pakistan is burdened with a $9.5 billion debt to China, largely accrued through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). This sum includes $7.5 billion for power plants and nearly $2 billion in unpaid energy bills. Political disputes and corruption allegations slowed project progress, and a 2019 IMF bailout forced Pakistan to decelerate CPEC initiatives. To manage the crisis, Pakistan has been compelled to take new loans to service old ones, creating a vicious cycle of debt and deepening its economic dependence on China, with the promised benefits of CPEC failing to materialize.

#2 Nepal’s Infrastructure Financing Strain

By 9 September 2025, Nepal’s public debt stood at $20 billion, with external debt at $10.5 billion. China accounts for approximately $300 million of this, financing projects like the $216 million Pokhara International Airport and the Trishuli 3A Hydropower Project. These Chinese loans are often expensive and come with strict conditions. Crucially, funded projects like Pokhara Airport are not generating sufficient revenue, making repayment difficult. This situation increases Nepal’s financial vulnerability and amplifies Beijing’s political influence within the country, posing a long-term strategic challenge.

#3 Bangladesh’s Deepening Financial Reliance

On 12 July 2025, reports indicated Bangladesh’s growing dependence on Chinese financing, with $6.1 billion in existing loans and a recent $2.1 billion top-up in March 2025. An additional $5 billion soft loan was requested in 2024. These funds support major infrastructure like the Padma Bridge and Payra Port. With Bangladesh’s economy struggling, it relies heavily on external borrowing. China has extended repayment terms to 30 years, securing long-term economic leverage. This dependence on loans for critical infrastructure risks pushing Bangladesh into greater financial vulnerability and deeper Chinese influence.

#4 Kenya’s Costly Railway Investment

As of 24 April 2025, China became Kenya’s largest bilateral creditor, with debt exceeding $8 billion. A significant portion, $5 billion, was used to construct the Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) from Nairobi to Mombasa. This reliance on Chinese infrastructure loans has created a heavy sovereign debt burden. The government has found itself needing to seek additional loans, including a requested $1 billion and debt restructuring, simply to complete stalled projects. This cycle deepens Kenya’s financial dependence on China, limiting its fiscal options and granting Beijing substantial economic influence.

#5 Zambia’s Mining Sector Leverage

By 24 March 2025, Zambia owed China over $4 billion, a key component of a broader $6.3 billion debt restructured in 2023. These loans are tied to Chinese investment in the copper mining sector, which provides 70% of Zambia’s export earnings. This dominance creates profound economic dependence. The debt obligations restrict Zambia’s ability to regulate Chinese corporate practices strictly. Furthermore, the restructuring terms favor Chinese creditors, giving Beijing significant leverage over Zambia’s national policies and corporate governance, effectively trading economic sovereignty for financial relief.

#6 Cambodia’s Strategic Debt

On 17 March 2025, Cambodia’s outstanding debt to China was approximately $4 billion, representing over one-third of its total public debt and nearly a tenth of its GDP. These loans primarily finance infrastructure such as roads, airports, and a new $1.7 billion canal project. This heavy borrowing has created a deep economic dependence on China, making Cambodia’s economy highly vulnerable to shifts in Chinese policy or financing. The debt relationship extends beyond economics, influencing Cambodia’s geopolitical alignment and limiting its autonomy in regional and international affairs.

#7 Angola’s Oil-for-Credit Model

Reported on 3 September 2024, Angola has borrowed over $45 billion from China since 2002, with about $17 billion remaining unpaid. Chinese debt constitutes 40% of Angola’s total, with half its annual budget dedicated to repayments. The “Angola Model” involves repaying loans with oil exports. However, falling oil production and prices have crippled this model, leaving Angola struggling to earn revenue for debt servicing. To avoid default, Angola is using funds from a Chinese escrow account, which depletes reserves needed for other critical national needs, deepening the economic trap.

#8 Laos’s Unsustainable Projects

As of 23 July 2024, Laos’s public debt was $13.8 billion, over 100% of its GDP. China holds about half of its $10.5 billion foreign debt, financing major projects like hydroelectric dams on the Mekong River and the Boten–Vientiane high-speed railway. These projects have not yielded expected returns, suffering from energy overcapacity and underuse. Chinese loans carry high interest rates near 4%, exacerbating the burden. This has led to heavy political and economic dependence on Beijing, severely limiting Laos’s ability to manage or renegotiate its crippling debt obligations.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.