Author and historian TS Krishnan recently published a Tamil translation of Ganga Devi’s Madhura Vijayam. The book is titled கங்கா தேவியின் மதுரா விஜயம் (Ganga Deviyin Madhura Vijayam). Before getting into his translation, here is some history. Beyond being a passionate Madurai-ite and a history buff, a few other things drew me close to Ganga Devi and her work around fifteen years ago. My interest was kindled by a few usual tropes that people use to deride Sanatana Dharma: Education for women was (only) made possible by the Dravidian movement, no one but Brahmins had access to Sanskrit, are some of the popular ones still being peddled.

Sanskrit And Women

We don’t have to go way back into the Vedic age to cite the examples of Gārgī Vāchaknavī, Vadava Pratitheyi, and Sulabha Maitreyi to prove our point. Many women scholars of Sanskrit existed around the time of Ganga Devi, and most were not Brahmins. Rajasekara, a dramatist from 950 CE, says that gender isn’t a determining factor; it is the inner genius.

Women like Tirumalambika, who lived around 1530 CE, wrote a Champukavya, Varadambikaparinaya, immortalising Achutadevaraya’s marriage to Varadambika. Achutadevaraya was the successor of Krishnadevaraya, the emperor of Vijayanagara. We then had Ramabhadrambal in Thanjavur, who wrote Raghunathabhyudaya, honouring her husband, Raghunatha Nayak (1600 CE), who was part of the Thanjavur Nayak Dynasty. His court also patronised another woman, poet Madhuravani, who translated into Sanskrit the Mahakavya that Raghunatha Nayak wrote in Telugu, Valmikicharitram.

Historically, numerous women poets and scholars of Sanskrit stood as tall as their male counterparts. Most of these great women were not Brahmins, dispelling the Dravidian trope that non-Brahmins were prohibited from studying Sanskrit.

Madhura Vijayam – Real History and Some Personal History

Madhura Vijayam or Virakamparayacharita is the history of Kumara Kampana, the prince of Vijayanagara and the son of Bukka I, the emperor who succeeded his brother, Harihara I, as the emperor of the Vijayanagara empire. The work traces Kumara Kampana from birth to his conquering and liberating Madurai from the tyrannical Islamic Sultanate. The author of this book is Kumara Kampana’s Queen consort, Ganga Devi, a Sanskrit poetess par excellence.

The work dates from around 1380 CE but was considered lost until about 108 years ago. In 1916, Pandit Ramasvami Sastriar discovered a palm-leaf manuscript of this great work in Trivandrum. But that wasn’t the complete work. There are many incomplete parts. It is unclear how much of this great work is lost. Apart from this manuscript, there are supposed to be two more, one in Lahore and another in Trivandrum (a second).

This great work was salvaged, printed in Trivandrum, and made available in 1924. The original, which was edited and published by Harihara Sastri and Srinivasa Sastri in 1924, retailed for twelve Annas, a book whose PDF version I could read.

The other two—the First, “The Conquest of Madhura by Ganga Devi,” translated by Dr. Shankar Rajaraman and Venetia Kotamraju—were published in 2013. This beautiful translation in English has the Sanskrit verses side by side and is a lovely book I lost before one of the translators, Dr. Shankar, was kind enough to send me an autographed (in Sanskrit) copy in 2021. The second is a Tamil translation கங்காதேவியின் ‘மதுராவிஜயம்’ (Gangadeviyin ‘Maduravijayam’) by Srivaishnavasri. A. Krishnamacharyar, published in 2010. This work starts with some background history and then goes into the Tamil translation of the verses.

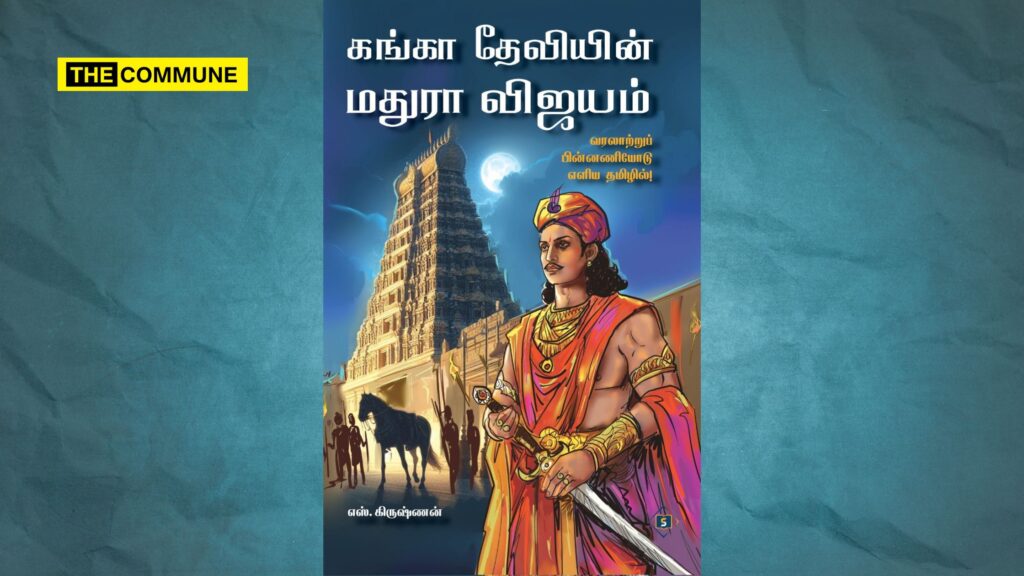

கங்கா தேவியின் மதுராவிஜயம் – The Translation By TS Krishnan

This is an excellent, easy-to-handle Tamil translation of the verses of Ganga Devi’s work. Krishnan, an IT professional and history buff, knows the syntax of presenting translations. He doesn’t jump straight into the work but provides you with a lot of history and background before he takes you to visit Ganga Devi’s work. The background he gives is like a perfect starter before the main course is served, the Tamil translation of the great work.

The translation covers the nine cantos of the work. Each canto starts with a summary of what one can expect, followed by the verse-by-verse translation of the work. Krishnan also provides timely interludes between verses, explaining certain things implied by the author but that a person reading a translation might not grasp. The author’s extensive research is apparent in his presentation.

Why Read The Book?

This is in lucid Tamil prose anyone can read, understand, and appreciate.

Understand our real history and start discerning good from bad.

To realise what our ancestors have gone through to save our temples and culture and start working towards restoring Bharat’s glory.

So, if you read Tamil and want to learn more about our history and culture. Grab this book.

Let us not forget

धर्मो रक्षति रक्षितः

Tiruvalluvar says this more directly

அறத்தினூஉங்கு ஆக்கமும் இல்லை அதனை

மறத்தலின் ஊங்கில்லை கேடு.

Thirukkural (Chapter 4, The Glorification of Righteousness, 31)

There is no greater good than Righteousness, nor no greater evil than the forgetting of it.

The Kural or The Maxims of Thiruvalluvar by VVS Aiyer

Raja Baradwaj is a marketing communications professional who works with a leading technology multinational company. He is an avid reader, history buff, cricket player, writer, and Sanskrit and Dharma Sastra student.

Subscribe to our Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram channels and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.