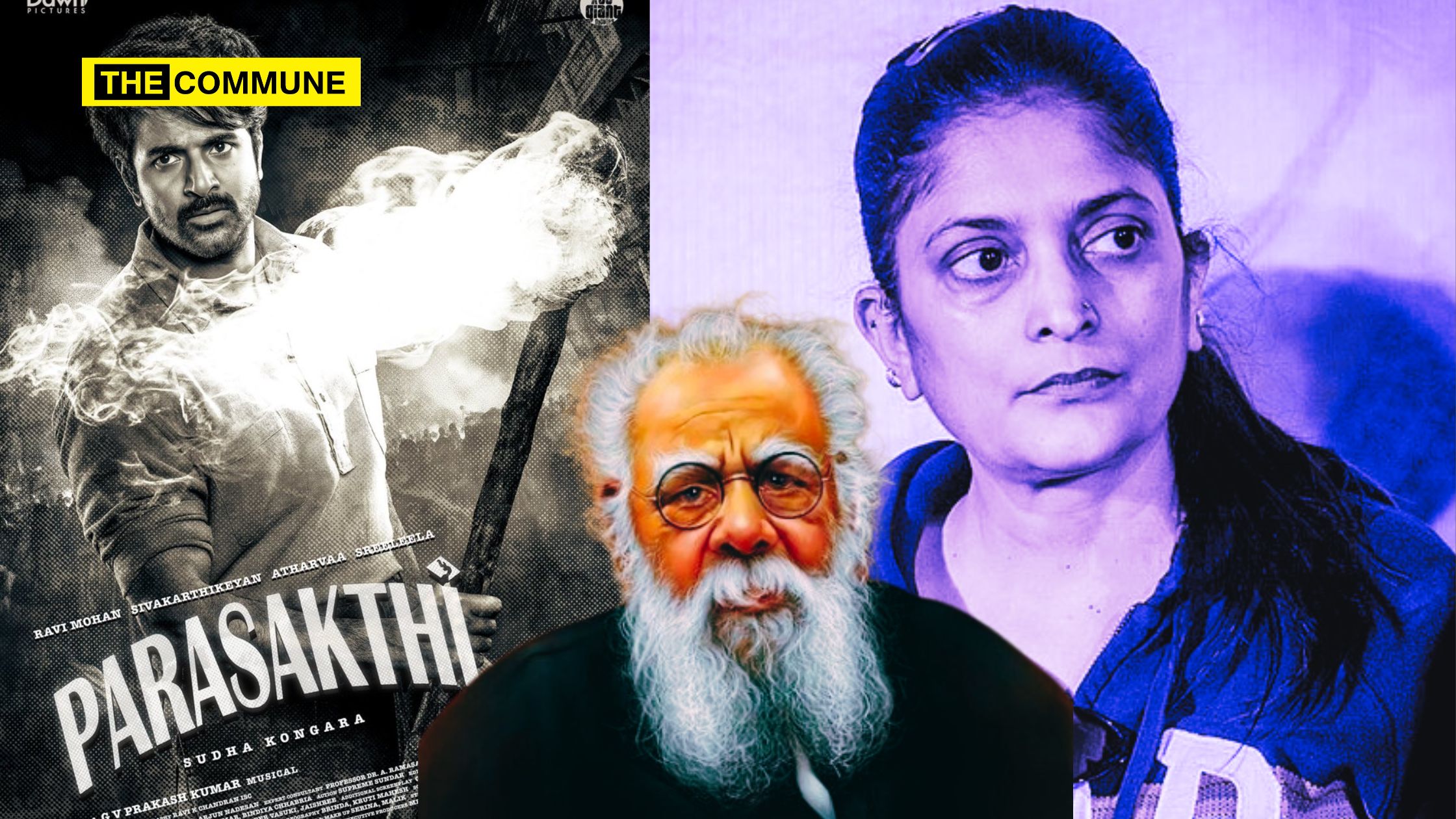

The upcoming period drama, Parasakthi, directed by Sudha Kongara, is set to shed light on the anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s in Tamil Nadu.

Kongara has earned a reputation for distorting original stories and twisting narratives to suit the Dravidianist propaganda. As seen in her previous film Soorarai Potru, which claimed to depict the life of Simplifly Deccan (Air Deccan) founder Captain GR Gopinath, she had cunningly inserted the Dravidianist ideology into the film. Suriya who played the character of Gopinath, a Brahmin in real life, was depicted as a follower of rabid anti-Hindu and anti-Tamil demogogue EV Ramasamy Naicker (hailed as ‘Periyar’ by his followers). And the villains in the film were all, no prizes for guessing, Brahmins!

Interestingly, the Hindi version of the film’s song in Soorarai Potru which was released had no references to EVR while the Tamil version had EVR’s picture and a black shirt-borne Suriya.

Since she has a history of lacing true stories with distortions about Brahmins —it’s crucial to address the false portrayal that might surface once again in her new venture, Parasakthi in which she may possibly distort key events like the anti-Hindi agitations. So, before Sudha Kongara goes on to spin her Dravidianist narrative in her upcoming film, let’s examine the true essence of these agitations and the role—or rather, the lack thereof—played by EVR (E.V. Ramasamy), the figure often hailed as a champion of Tamil rights by Dravidianists.

The 1965 Anti-Hindi Agitation

The 1965 anti-Hindi agitation was part of a broader political struggle in Tamil Nadu. The roots of the movement can be traced back to earlier protests, such as those in 1938, which involved widespread picketing in schools (particularly the Hindu Theosophical School) and government offices. This protest, which also led to the death of two demonstrators, was the first major indication of resistance to the imposition of Hindi. However, the 1965 agitation was not as pure-hearted as often portrayed.

The 1965 anti-Hindi agitations were nothing new to TN, there were widescale protests even in 1938, where schools (Hindu Theosophical School mainly) and govt offices were picketed, and even resulted in the death of 2 protestors (including Thalamuthu).

The fact is, the tables… https://t.co/cW4Np1Yjr4 pic.twitter.com/M7k8WynBC9

— Tamil Labs 2.0 (@labstamil) January 30, 2025

EVR, the so-called “leader of Tamil rights,” who had supported the 1938 protests, turned his back on the 1965 agitation, calling it a political stunt. While the movement gained significant momentum in the 1960s, EVR expressed no support. Instead, he made it clear that he did not view the agitations as an expression of genuine love for the Tamil language. His stance was political, aiming to gain influence in a region previously dominated by the Congress party.

Interestingly, during the 1965 protests, EVR contradicted his earlier views. In a complete reversal, he openly advised people to learn Hindi, even at a time when the anti-Hindi sentiment was at its peak. His political opportunism was evident when he attempted to downplay the significance of Tamil culture in favor of political leverage. EVR’s support for Hindi was clear when he claimed that learning the language could be useful for securing jobs in the government.

The Tamil Nadu of the 1960s was a political battleground where EVR’s influence was starting to wane. The opposition, led by figures like Rajaji, who had previously opposed the imposition of Hindi, now supported the anti-Hindi agitation, further complicating the political landscape. EVR’s opposition to the 1965 protests was nothing more than a tactical move aimed at asserting his own relevance.

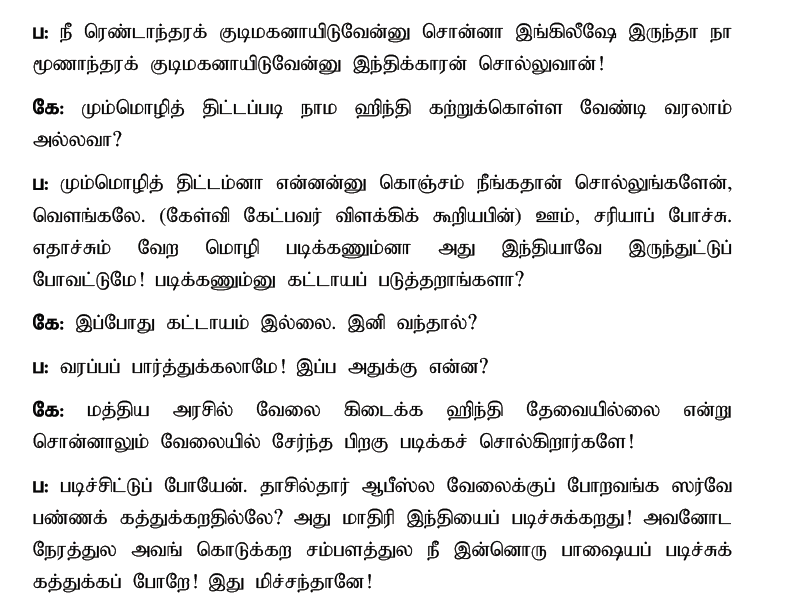

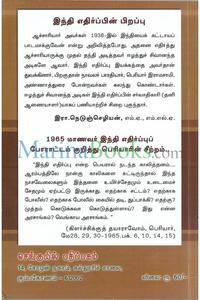

In an interview to Vikatan from 1965, EVR was asked about the three-language plan, and his response revealed the true nature of his indifference to the Tamil cause. He dismissed the idea that Hindi was an imposition, suggesting that it was simply another language to learn, and went so far as to say that learning Hindi could be beneficial if one worked in a government office. EVR’s lack of commitment to the Tamil cause becomes painfully clear in this exchange, as he trivialized the genuine concerns of Tamil speakers and prioritized his own political ambitions over the preservation of Tamil culture.

It is vital to understand that the 1965 anti-Hindi agitation had far more to do with political maneuvering than genuine love for Tamil or its culture. EVR’s role in the agitation was not one of a martyr for Tamil rights but rather that of a man trying to secure power and position within a changing political landscape. His reversal on the issue of Hindi is proof enough of his true motives.

Vikatan's EVR interview from 1965 during Anti Hindi agitations. They have a slightly redacted version of this on their website still.

Guys like @athreya49 should read all this, and call EVR a Sanghi or other namecalling he routinely indulges in pic.twitter.com/zkGEtjm0ej

— Tamil Labs 2.0 (@labstamil) January 30, 2025

The Original Anti-Hindi Agitation Of 1938

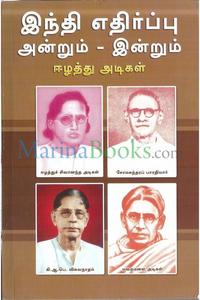

The anti-Hindi agitations in Tamil Nadu were not initiated by EVR, contrary to popular belief. The earliest opposition to Hindi imposition was led by Saivite scholars and Tamil intellectuals such as Eezhathu Sivananda Adigal, Arunagiri Adigal, Maraimalai Adigal, Sanmugananda Adigal, K.A.P. Viswanathan, Somasundara Bharathiyar, and Vimalananda. These figures were the first to condemn the 1937 decision of the Rajaji-led government, which mandated Hindi education in schools.

In his book “Hindi Edhirpu: Andrum Indrum” (Opposition to Hindi: Then and Now), Eezhathu Sivananda Adigal documented that the first major protest against Hindi imposition occurred in 1937, with 120 people demonstrating outside the Chief Minister’s residence. By the third day, around 60 protesters were arrested. At the time, EVR distanced himself from the movement, dismissing it as an ineffective Congress-style agitation. He reportedly even offered money to protesters to return to their native places, prompting Eezhathu Adigal to respectfully request EVR to stay out of the issue, considering that as a greater service to Tamil.

With the arrests of key leaders like Eezhathu Sivananda Adigal, Arunagiri Adigal, and Sanmugananda Adigal, the movement briefly lost direction. However, upon witnessing the public’s strong response to the protests, EVR later assumed leadership, much like he had done during the Vaikom Satyagraha.

Eezhathu Adigal further noted that EVR later projected himself as the pioneer of the anti-Hindi movement, even though records show that he was arrested during the agitation and released six months later. In a surprising turn, he abruptly withdrew the protests in 1939, before the Rajaji government had even repealed the decision. When questioned by the press about this sudden move, EVR reportedly stated:

“The anti-Hindi agitations were used by me only to trouble the Congress government ministers. I do not care if Hindi gets imposed or Tamil perishes.” (Hindi Edhirpu: Andrum Indrum, Page 30).

This led Eezhathu Sivananda Adigal to challenge EVR’s authority over the movement, asserting that he had no right to call off the protest. On November 4, 1939, Adigal announced a renewed demonstration in front of the Governor’s bungalow. Ultimately, it was only on February 21, 1940, that the Rajaji government officially revoked the Hindi mandate.

EVR Hated Tamil

That’s right. EVR hated Tamil so much that he called Thirukkural as faeces. If one reads the speeches and editorials of EVR in his mouthpieces Viduthalai and Kudiarasu, it would be evident as to what his views on Tamil and Tamilians were.

1. EVR Dismissed Tamil As A ‘Barbarian Language’

In an editorial published in Viduthalai on October 11, 1967, EVR referred to Tamil as a “kaatumiraandi mozhi” (barbarian language). This was not an isolated remark—throughout his life, he belittled Tamil, advocating for its abandonment in favor of English. He even went so far as to say that “Tamil is a language not even useful for begging.”

2. EVR Rejected The Tamil Epic Silappadikaram

Silappadikaram, one of Tamil Nadu’s most revered literary works from the Sangam era, was dismissed by EVR as Aryan propaganda. In a speech on March 30, 1951, he described it as a collection of superstitions that promoted the subjugation of women.

3. EVR Condemned Kamba Ramayanam

Kamba Ramayanam, the Tamil adaptation of the Ramayana, was denounced by EVR as a “storehouse of falsehood”. He claimed that such literature betrayed the Tamil race, arguing that its popularity reflected the lack of intelligence and self-respect among Tamils.

4. EVR Insulted Tamil Society

Between October and November 1967, EVR wrote multiple articles portraying Tamils as backward and irrational. He argued that their inventions and traditions—such as the grinding stone, oil lamps, and bullock carts—were primitive and of no practical use. He even claimed that Tamils had no concept of time and had borrowed it from the English.

EVR openly derided Tamil society, describing its people as lacking racial consciousness, self-respect, nationalism, and even basic humaneness.

5. EVR Attacked Tamil Scholars

In a Viduthalai editorial dated March 16, 1967, EVR declared that Tamil scholars and pundits deserved to be imprisoned for life and hanged, accusing them of failing to contribute to society’s progress. He even ridiculed the World Tamil Conference, calling it a “census to enumerate fools.”

6. EVR Rejected Saivite And Vaishnavite Tamil Literature

EVR dismissed Tamil Hindu devotional texts such as Tevaram, Tiruvasagam, Tirumandiram, and Divyaprabandham as worthless and harmful to Tamil society. He also condemned Periyapuranam, a literary classic detailing the lives of the 63 Nayanmars, as an instrument of religious oppression.

7. EVR Equated Thirukkural To Excreta

Thirukkural, revered as one of the greatest works of Tamil literature, was scathingly criticized by EVR. Initially, he praised it, but later dismissed it as “feces placed in a golden plate.”

In the Viduthalai issue dated June 1, 1950, EVR condemned Thirukkural for promoting ideas that, in his view, opposed rationalism. When asked what Tamils would have left if Thirukkural was discarded, he reportedly responded:

“I am telling you to remove the excreta that stinks in the room, and you are asking me what to replace it with?”

8. EVR Insulted Tamil Poet and Freedom Fighter Subramania Bharathi

EVR had contempt for Subramania Bharathi, the iconic poet and nationalist leader. In the journal Ticutar, he mocked Bharathi for calling Tamil the sister language of Sanskrit. He even compared Bharathi to a rat, sarcastically remarking:

“They say Bharathi is an immortal poet. Even if a rat dies in an agraharam, they would declare it to be immortal. Why should this be so? Because he sang praises of Tamil and Tamil Nadu? What else could he do? His own mother tongue, Sanskrit, has been dead for years. What other language did he know? He cannot sing in Sanskrit.”

Before Sudha Kongara distorts history to paint EVR as a heroic figure in the anti-Hindi agitation, it is essential to remember that his actions were driven by political opportunism rather than a deep-seated belief in the protection of Tamil. Far from being a protector of Tamil identity, EVR’s actions were detrimental to the Tamil cause, and his opportunistic U-turns only serve to expose his true character. Let us not allow historical distortions to glorify a man who was, in fact, anti-Tamil.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.