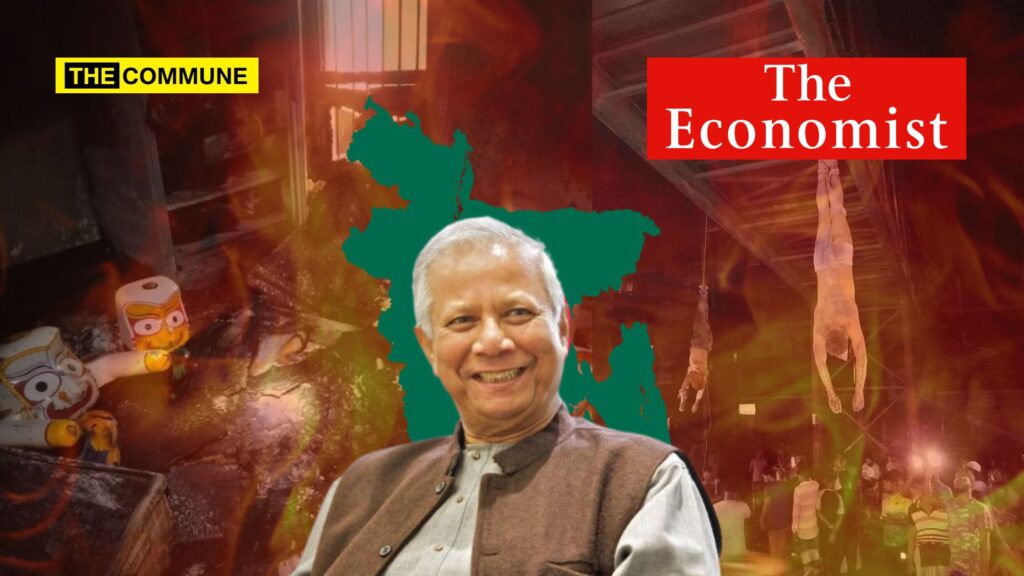

The British weekly The Economist has met with mockery after naming Bangladesh its “Country of the Year,” citing recent political developments. The magazine praised Bangladesh for “toppling a despot” and “taking strides towards a more liberal government.” However, the decision has been met with backlash, especially given the country’s increasing political instability, economic turmoil, and escalating violence against minorities, particularly Hindus since Sheikh Hasina’s fall from power.

The award has left many questioning the magazine’s judgment, particularly in light of Bangladesh’s ongoing struggles with corruption, economic decline, and rising communal tensions. Critics have pointed out that the country’s descent into chaos contradicts The Economist portraying Bangladesh as a success story. The magazine’s recognition came despite the increasing threat of Islamic extremism in the region, which The Economist acknowledged, along with the urgent need for Bangladesh to repair its relationship with India and hold elections on time.

A Flawed Narrative Of The Economist’s Rationale

In justifying its decision, The Economist stated that “the winner is not the richest, happiest, or most virtuous place, but the one that has improved the most in the previous 12 months.” This year, Bangladesh was chosen over other contenders such as Syria, Argentina, South Africa, and Poland. The magazine acknowledged the toppling of the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria but noted that the quality of the successor government remained uncertain. Similarly, it described Bangladesh as a country that had also “overthrown an autocrat,” linking it to their broader agenda of promoting “regime change” in the name of liberalization.

Bangladesh is The Economist’s country of the year. Great choice. We can talk about the massive challenges faced by the interim government, but it’s important to recognize the tremendous significance of what many have called the first “Gen Z revolution.”https://t.co/PYiaaqVTuV

— Michael Kugelman (@MichaelKugelman) December 21, 2024

Questioning The ‘Improvement’ Claim

The Economist defended its decision by asserting that the award is not for the wealthiest or happiest countries, but for those showing the most significant improvements. Yet, it is difficult to reconcile this claim with the current reality in Bangladesh. The country has faced severe economic challenges, including demands for 50,000 tonnes of rice from India and unpaid electricity bills to the Adani Group. The textile sector, a backbone of the economy, is also in disarray. Despite these setbacks, The Economist lauds the nation’s economic stability as a sign of progress.

This raises the question: can a nation truly be considered to have “improved” when its economic situation is faltering, and when such instability is coupled with rising violence and persecution of minority communities?

Ignoring Violence Against Minorities

One of the most glaring oversights in The Economist’s coverage is the rising violence against Hindus in Bangladesh since Hasina’s removal. Within days of the regime change in August 2024, over 200 attacks on Hindu temples, businesses, and homes were reported. These assaults on the Hindu community, including the destruction of religious idols and attacks on Hindu leaders, have escalated sharply. From 47 reported attacks in 2022, the number rose to 302 in 2023, and by 2024, the figure soared to 2,200—an alarming increase of over 4,500%.

Yet The Economist chose not to address this horrific surge in targeted violence. The question arises: can a country be said to be improving when its minority communities are facing increasing persecution, with little or no justice?

The Plight Of Hindus In Bangladesh

The violence against Hindus in Bangladesh reflects a broader pattern of religious intolerance that has intensified in recent months. Radical Islamist groups have increasingly targeted Hindus, accusing them of blasphemy and using such charges as a pretext for violence. The persecution has extended to Hindu organisations such as ISKCON, with leaders like Chinmoy Krishna Das Prabhu being arrested under fabricated charges. The interim government has cracked down on Hindu protests, accusing them of sedition, showing a clear attempt to suppress the rights and freedoms of the Hindu community.

Despite mounting evidence of these atrocities, international organizations and media outlets, including The Economist, have failed to adequately address the religious dimensions of the violence. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has notably ignored these hate crimes, reframing them as part of broader political unrest. Similarly, the Indian news outlet The Wire and the BBC have downplayed the intensity of the persecution, often labeling the attacks as politically motivated rather than religiously driven. This whitewashing of anti-Hindu violence serves to minimize the scale of the atrocities and exonerate those responsible.

Selective Morality Of The West

The selective morality exhibited by Western media is particularly troubling when it comes to reporting on violence against Hindus. While The Economist, The Wire, and the BBC often ignore or minimize the role of radical Islamist groups in these attacks, they consistently highlight religious violence when it involves other communities. This double standard contributes to a global narrative that disregards the plight of Hindus, especially in countries where they are a minority.

The failure to address the rising anti-Hindu violence in Bangladesh and the broader South Asian region speaks to a larger issue in Western media coverage: a tendency to downplay or misinterpret the persecution of Hindu communities, often framing such violence as a byproduct of political or economic strife, rather than a deliberate religious targeting.

The Economist’s Anti-Hindu Bias

Over the years, The Economist has developed a clear bias against Hinduism, Hindu nationalist movements like Hindutva, and the Indian government, particularly under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The magazine has consistently portrayed Hindu nationalism as a form of exclusionary extremism, without engaging with its historical, cultural, or political context.

For instance, The Economist’s coverage of Hindutva has often reduced it to a narrow, supremacist ideology, ignoring its roots in India’s anti-colonial struggle and its complex cultural philosophy. Similarly, the magazine’s criticism of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in India overlooked the law’s intent to provide refuge to persecuted minorities from neighboring countries, framing it as discriminatory without addressing the context of religious persecution faced by Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, and other non-Muslim minorities in these nations.

The publication’s portrayal of Hindu organizations like the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) has also been consistently negative, focusing on unsubstantiated allegations while ignoring their extensive charitable work. The Economist’s coverage of Hindu cultural expressions, such as the construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya or religious tourism initiatives, often frames them as attempts to consolidate Hindu dominance, disregarding their deep cultural and spiritual significance.

Bangladesh’s post-Covid recovery has been slow, with high inflation, a balance of payments deficit, and other vulnerabilities in the financial sector. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has downgraded its economic projections for the country, forecasting a slowdown in GDP growth and an increasingly precarious fiscal situation. In addition, local business elites and oligarchs continue to exert significant influence over the economy, stifling much-needed reforms.

Political critics have raised concerns about the growing repression of minorities, citing violent attacks on Hindus and the imprisonment of activists like Chinmoy Krishna Das, who campaigned for better protection of minority rights. Many have questioned the magazine’s portrayal of Bangladesh as a beacon of progress, given these issues.

The Economist’s Role In Promoting Regime Change?

The choice of Bangladesh is seen by some as part of The Economist’s broader bias towards regime change, especially in countries where autocratic leaders are ousted in favor of new, often unstable, governments. Critics have pointed out that previous winners of the “Country of the Year” title, such as Tunisia (2014), Myanmar (2015), Armenia (2018), and Ukraine (2022), have experienced significant political and economic challenges after receiving the accolade.

History of The Economist Countries of year: except for France, all have significant negative consequences! We can imagine what is in store for Bangladesh!

– **2014, Tunisia**:

– **Assassination of Mohamed Brahmi**: The assassination of left-wing politician Mohamed Brahmi led…— JH (@jagdish_2204) December 21, 2024

For instance, Tunisia’s post-award period was marked by political turmoil after opposition leader Mohamed Brahmi’s assassination, triggering widespread unrest.

Myanmar’s selection in 2015 was followed by the devastating Rohingya crisis. The situation worsened when the military junta overthrew Aung San Suu Kyi’s democratic government, plunging the nation into an ongoing civil war.

In 2016, Colombia received the title after signing a historic peace agreement with FARC. However, initial referendum rejection caused complications and delays. Recent reports from the Norwegian Refugee Council reveal that 8.4 million Colombians continue to live in conflict zones, indicating the peace process remains incomplete.

Armenia’s 2018 recognition came after the Velvet Revolution, where peaceful protests led by Nikol Pashinyan forced Prime Minister Serzh Sargsyan’s resignation over allegations of corruption and incompetence. However, the nation subsequently faced multiple crises: the COVID-19 pandemic, territorial losses in the Azerbaijan conflict, and a refugee crisis in 2023, all of which have severely impacted its economy.

Bangladesh’s economic challenges are another major reason for criticism of The Economist’s choice. Despite initial gains made under the leadership of Sheikh Hasina, including lifting millions out of poverty through industrial development, corruption and cronyism have undermined economic progress. The caretaker government has released reports detailing the extensive corruption within Hasina’s administration.

The country’s economic situation has worsened post-regime change, with GDP growth projections dropping and inflation remaining high, particularly in food and energy sectors. Analysts have warned that without swift action to boost investments and stabilize the economy, Bangladesh risks a full-blown economic crisis.

While the recognition does not inherently doom a country to failure, the history of past winners has led many to question the criteria and foresight behind the selection process. The Economist’s decision to award Bangladesh the title raises important questions about the magazine’s priorities and its understanding of what truly constitutes progress.

The Economist’s choice of Bangladesh as “Country of the Year” while ignoring the systemic persecution of its Hindu minority speaks to a broader issue of selective reporting in Western media. By prioritizing a superficial narrative of political change over the lived experiences of persecuted minorities, The Economist has undermined its credibility as an impartial observer.

(With inputs from India Today & OpIndia)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.