The image of Rāma as Maryādā Puruṣottama – the best among men, the ideal man – is widespread in the Hindu psyche. Rāma is the embodiment of Dharma, always keeping with righteous action, truth and duty. Even with the rise and fall of many kingdoms and empires and despite the several ebbs and flows of Hindu civilisation, this strand of thought has remained in the Hindu mind for more than a period of two thousand years.

However, Rāma is not only the ideal man, but He is also the ideal monarch. As the archetypal ideal ruler who exemplifies Dharma, He is also responsible for safeguarding Dharma from Adharma.

The idea of a State governed under Rāma – the Rāmarājya – has influenced the foundational principles of Hindu civilisation over these past centuries. Harmony and happiness all around characterises the Rāmarājya.

What Rāmarājya is and isn’t

In the Rāmarājya, statecraft is envisioned as a partnership between the deity and the earthly ruler, with Dharma as the nucleus of the State. The earthy ruler – be he elected or born into the role – upholds Dharma.

The State protects and preserves ancient traditions and practices; it does not interfere in them by alluding to naïve ideas that are incompatible with the smooth functioning of Hindu society.

Home, Family and Social bonds are strengthened and protected; they are not diluted by progressive laws and an over-reaching judiciary.

The sovereignty of the country is protected in such a State, be it on the land or marine borders, or even on the economic frontiers. Autonomy is not handed over to a globalist, imperial power in exchange for a few paltry trinkets.

The State funds true merit in the arts and sciences and does not disburse funds and taxpayer-funded employment to groups who hold the State ransom with threats of violent riots and unfavourable electoral mandates.

Upliftment of the poor and the needy does take place, but not through draconian laws that institutionalise discrimination and persecution of certain groups. Neither does the State engage in social engineering through handouts to establish faux egalitarianism.

The State facilitates entrepreneurship and financial activity. Citizen-citizen interactions and citizen-State interactions – such as those in the realms of industry, commerce, and taxation – are not made obscure and complicated by vested interests and bureaucratic red tape. There is no place for corruption and hubris.

The ruler of such a State does not claim to be a Nanny who knows what is best for the Children. He does not seek to bring in reform for reform’s sake, as a Statist government machinery mutely stands by. The ruler does not tamper in the inherent diversity of practices and rituals; he does not seek to impose a uniform and quasi-monotheistic set of practices from up above in order to create superficial conformity and glibly, and falsely, call it unity. He is not enamoured with the State’s right to run people’s lives for them.

The elimination of Adharma as central to the preservation of Dharma

But most important of all the obligations of a Dhārmika ruler towards the People is the destruction of Adharma. The extermination of foes will involve tasks that are considered difficult and uncomfortable. These acts will be considered cruel by many. But the Dhārmika ruler does not shy away from them in order to protect one’s People.

In the Bāla Kāṇḍa of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa, there is a chapter where Viśvāmitra convinces Rāma that it is his duty to slay the dreadful Tāṭakā.

Tāṭakā was a very powerful yakṣiṇī. She devastated the land with wickedness and impiety, tearing asunder its sacredness. Therefore, the great Viśvāmitra beckons Rāma to slay her:

“O Rāma, thou must slay this wicked and impious demon Tāṭakā, who ravages the land. For the good of the Brāhmaṇas and the king, O Rāghava, accomplish this; do not hesitate to destroy this vile yakṣiṇī. It is the duty of a warrior to protect those of the four castes. A prince must not eschew deeds that are painful and difficult, for the preservation of his people. It is according to the law of eternal Dharma, O Rāma, that even deeds that appear ruthless are permitted to those appointed to protect their subjects. O Rāghava, Tāṭakā is wholly evil, and therefore must be destroyed […] Fulfill thy duty and slay this yakṣiṇī without delay.”

However, Rāma, who possesses great tolerance and kindness, is still reluctant. He says to his brother Lakṣmaṇa:

“She is horrible, versed in black magic and hard to subdue, but it is not proper to deprive a woman of her life. A woman is worthy of protection, therefore, I shall incapacitate her, by depriving her of the power of motion thus preventing her from doing further mischief.”

This is where Viśvāmitra comes in, with compelling and eye-opening arguments on why the resplendent Rāma must rid himself of such a perspective:

“Enough, she does not deserve further mercy; should you spare her, she will gain strength through her magic powers and will again break up our holy rites. The evening is approaching and in the evening rākṣasās are overcome with difficulty; slay her, therefore, without delay.”

Viśvāmitra’s argument on how wickedness and evil grow stronger upon being spared is noteworthy. Stress is also laid on the symbolism of a sacred land being bereft of ritual due to Adharma. Dharma rests on the efficacy of sacred conduct and that of conducting sacred and holy rites. Adhārmika foes destroy the traditional Hindu way of life.

However, a frequent and misplaced argument is made that such methods make Hindus akin to their Adhārmika foes, resulting in a “spiritual defeat”.

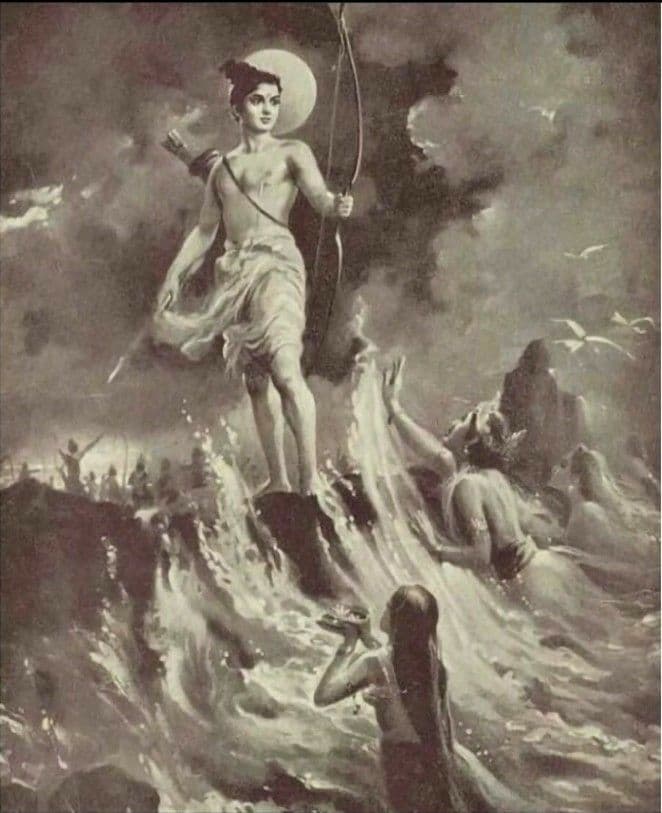

This misplaced argument can be answered in a chapter from the Yuddha Kāṇḍa of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. When the Ocean does not appear in his personal form before Him after requests and a wait of three nights, the enraged Rāma says:

“Indeed calmness, forbearance, kind spoken-ness and straight-forwardness – these qualities of noble men give weak results, when directed towards those having no virtues. This world honours that man, who boasts himself, is corrupt and shameless, runs about in all directions advertising himself and commits every kind of excess. In this world, it is not possible to obtain fame, glory or victory at the end of a battle, by conciliation. O, Lakṣmaṇa! Behold now this ocean, having its water made suffocated soon with its crocodiles floated on all sides and broken asunder by my arrows […] I will make the ocean with its multitude of conches, oyster shells, fishes and crocodiles, dry up now in this great battle. This ocean is considering me as an incapable man endowed as I am with forbearance. It is a great mistake to show forbearance to such an individual.”

And it is then, after Rāma has let loose fiery arrows which nearly dry up the seas, that the Ocean appears before Him and affords Him of a way to travel to Laṅkā with His army.

Thus, in any State where Rāma – and consequently, Dharma – is central, the annihilation of Adharma must be swift and thorough. As long as Adharma persists, the People cannot live in harmony and prosperity.

Rāmarājya is not a mere metaphor and neither is it an ideal of the past. It is an aspiration of the future that we must strive towards in the present, not just to maintain sublime principles, but for the sake of our people and our children. It is the goal that we must never forget.

Click here to subscribe to The Commune on Telegram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.