India’s reputation as a land of rich culture extends beyond art and tradition it is also home to architectural wonders steeped in rich spiritual history and mysticism. Among these, the Parasurameswara Temple in Gudimallam, a modest village located about 40 kilometers from Tirupati, stands out as a monumental site.

This sacred site is renowned for enshrining one of the earliest known Shiva Lingas in the Indian subcontinent, with scholars dating its origin anywhere between the 3rd century BCE and 2nd century CE, most likely constructed during the Satavahana era.

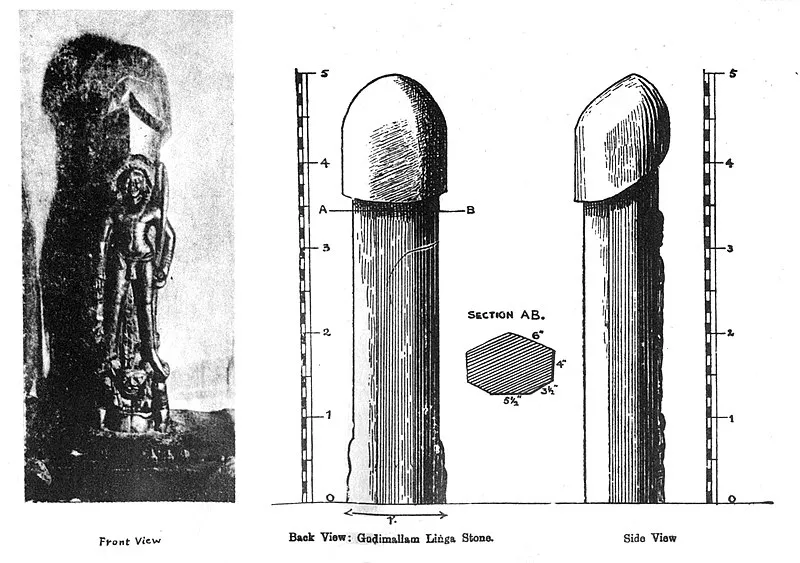

What sets this temple apart is the Gudimallam Lingam, a seven-sided monolithic sculpture carved from polished dark brown sandstone, believed to be sourced locally. The Lingam features a rare anthropomorphic depiction of Lord Shiva, portrayed as a dynamic hunter standing over a squatting Yaksha, or nature spirit. This high-relief image is considered to be one of the earliest surviving depictions of Shiva in human form.

The temple complex also includes shrines for Subramanya Swamy with consorts Srivalli and Anandavalli, Surya Bhagavan, and Vinayaka, reflecting a harmonious blend of Vedic, folk, and tribal traditions in worship. Local legends even hint at underground chambers and divine origins for the Lingam’s stone, contributing to its aura of mystery.

According to the Sthala Purana (temple legend), Parashurama, the warrior-sage and incarnation of Vishnu, performed rigorous penance at this very site to seek redemption for killing his mother at his father’s command. Offering a single flower each day from the Swarnamukhi River, he worshipped the Lingam until an incident occurred: Brahma, disguised as a Yaksha named Chitrasena, took the flower for his own offering. This led to a fierce battle between them, prompting Lord Shiva to appear and merge the three figures Brahma (the Yaksha), Vishnu (as Parashurama), and himself — into the Gudimallam Lingam, symbolizing the Trimurti (the trinity of creation, preservation, and destruction).

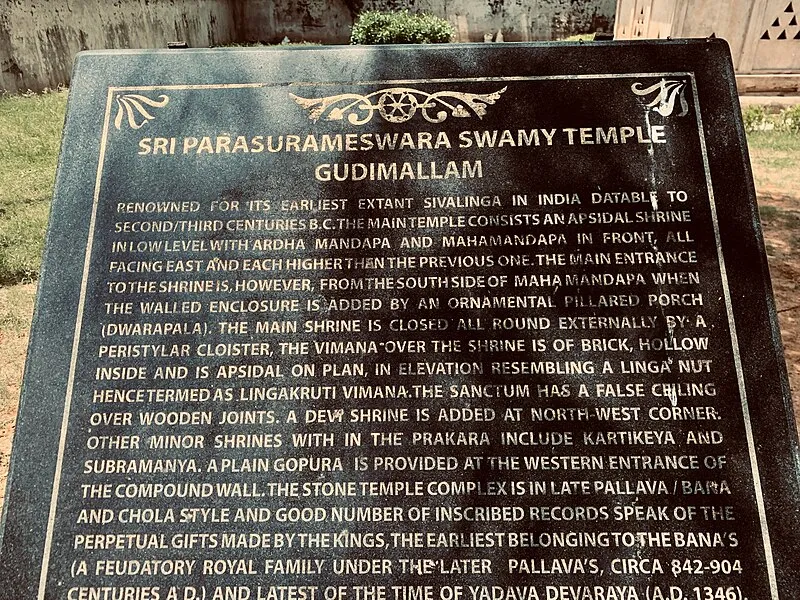

Inscriptions on the temple walls, mainly from the Pallava, Chola, and Vijayanagara dynasties, indicate that the temple was renovated and maintained consistently from the 1st or 2nd century CE onward. However, during Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) excavations in 1973, Black-and-Red Ware pottery, Satavahana-era bricks, and ancient structural remains were discovered, leading experts to date the original temple’s construction as early as the 2nd century BCE making this one of the oldest continuously active Shaivite temples in the country. This predates the earliest known inscriptions at the Tirumala Temple, which appear around the 9th century CE.

It is widely believed that the Lingam was originally worshipped in the open air, and that the surrounding stone structure was built later to house and protect it. The rectangular stone enclosure around the Lingam is thought to be part of its initial sanctum. The decorative style of the enclosure bears similarities to ancient Buddhist railing motifs, indicating possible cross-cultural architectural influence. Early construction likely involved wooden elements, many of which were later replaced or fortified during Chola and Vijayanagara renovations.

The temple came under the protection of the ASI in 1954, and since then, has undergone careful restoration work. Notably, the 1970s excavation to lower the floor revealed the full height of the Lingam and its intricately designed pedestal. The temple was first studied in detail by T.A. Gopinath Rao, an eminent archaeologist, who described it thoroughly in his work, Elements of Hindu Iconography. Rao measured the Lingam at approximately five feet tall, though its base remains buried, suggesting it may be taller than what’s visible.

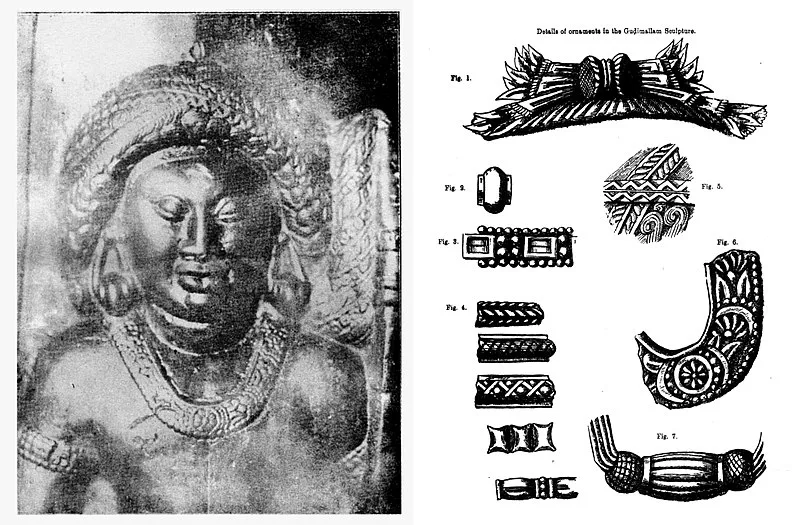

What truly distinguishes this Lingam is its unique design and symbolic depth. Unlike later Lingams that tend to be abstract and cylindrical, the Gudimallam Lingam features anatomical precision, including a visible glans and a subtle groove. The bent-backward posture and partially circular shape give the figure a striking presence. Shiva is rendered in the elegant tribhanga pose, adorned with braided hair, armlets, five distinct bangles on each wrist, and other tribal-style ornaments.

The sculpture lacks the sacred thread (yajnopavita), further emphasizing its non-Brahmanical, ascetic character. Instead of a crown, Shiva wears a turban-like headgear and a simple, wide dhoti that gracefully merges with the Lingam’s shaft — blending cosmic symbolism with human form. In his right hand, Shiva holds a ram or deer, alluding to his Bhikshatana (wandering ascetic) form, while the kamandalu (water pot) in his left hand represents purification and spiritual discipline. The battle axe (parasu) resting on his shoulder signifies both Parashurama’s identity and Shiva’s ferocious, protective aspect.

Beneath his feet lies a dwarf-like figure, often identified as Apasmara, the embodiment of spiritual ignorance a motif that would later appear in the Nataraja iconography. The intricate detailing from the tribal aesthetic to the ritualistic accessories suggests that this sculpture originated from pre-Vedic or folk Shaiva traditions, where Shiva was revered as a spiritual warrior and forest-dwelling ascetic rather than a royal deity.

Throughout centuries, the temple has been consistently referred to as the Parashurameswara Temple, as confirmed by numerous inscriptions. While none of the records mention its original builders, they meticulously document donations of land, livestock, and wealth, underscoring its central role in a community-based temple economy. This indicates that worship was sustained by the local populace, not just through royal endowments.

The architectural layout of the temple is equally remarkable. The square sanctum, terminating in an apsidal (semi-circular) rear wall, is among the earliest known Hindu temple designs, commonly associated with brick and wooden shrines from the 2nd century BCE. According to scholar Himanshu Ray, the apsidal form was not exclusively borrowed from Buddhist structures but was part of a shared architectural tradition among Hindu, Buddhist, and regional faiths. The Mayamatam, a South Indian treatise on temple architecture, explicitly includes apsidal layouts among its recommended temple plans.

Even during later reconstructions under the Cholas and Vijayanagara kings, the original apsidal structure was preserved, demonstrating a profound respect for the temple’s ancient sanctity. The curved rear wall resembles a womb-like enclosure, reinforcing the garbhagriha’s role as a cosmic center. The seamless architectural evolution from temporary wooden structures to enduring stone monuments echoes the spiritual permanence of the Lingam, which has remained a center of devotion for over 2,000 years.

Located about 40 kilometers from Tirupati, the temple can be accessed via Renigunta Airport and Papanayudu Peta, with regular buses available from Tirupati. However, there is currently no dedicated transportation to the temple.

For those with a passion for history, spirituality, and ancient art, the Gudimallam Parasurameswara Temple is a site of immense value. It not only offers a rare and early anthropomorphic representation of Shiva but also stands as a testament to the continuity of faith, architectural ingenuity, and cultural synthesis across millennia.

(This article is based on an X Thread By Lone Wolf Ratnakar)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.