A few days ago, makeup artist and distortionist Ruchika Sharma claimed Mariamman and Mary are the same – she did not speak history but peddled the same narrative as missionaries did.

She is once again back with another outrageous demand that exposes her knowledge of history.

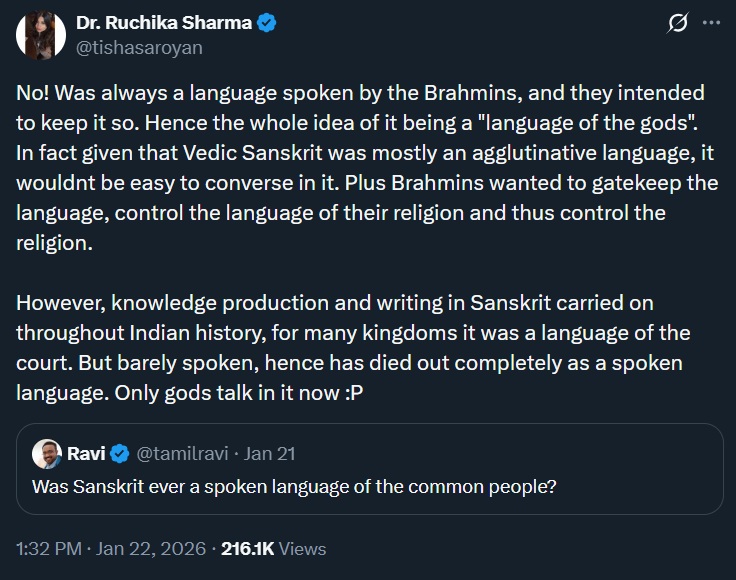

A social media argument triggered by makeup artist, who masquerades as a ‘historian’, Ruchika Sharma’s claim that Sanskrit was “always” spoken only by Brahmins has laid bare a bigger problem in today’s public history debates. Instead of discussing what ancient texts and inscriptions actually say, the discussion quickly shifted to who is “allowed” to speak on history and whose evidence can be dismissed outright. What should have been a simple question of reading sources turned into an exercise in ideological gatekeeping.

The controversy began with a question posed on X asking whether Sanskrit was ever a spoken language of the common people. Responding to this, makeup artist & self-proclaimed ‘historian’ Ruchika Sharma asserted that Sanskrit was “always a language spoken by the Brahmins”, that it was deliberately gatekept to control religion, and that while it functioned as a court language for many kingdoms, it was “barely spoken” and has therefore “died out completely as a spoken language”.

This sweeping claim was presented not as a hypothesis, but as settled historical truth.

It was then countered by author and historian TS Krishnan with a citation from Silappadikaram, one of the foundational Tamil epics, along with inscriptional and historical material showing Sanskrit’s social presence in Tamilakam.

Another entirely ignorant take from a so-called “history degree holder.”

Even in Tamilakam—where Sanskrit was not the primary spoken language—Sanskrit was widely known, spoken, and understood across sections of society. The commentary on the Tamil epic Silappadhikaram makes this… https://t.co/98h6xu66ei pic.twitter.com/yc7O3swlH7

— 𑀓𑀺𑀭𑀼𑀱𑁆𑀡𑀷𑁆 🇮🇳 (@tskrishnan) January 22, 2026

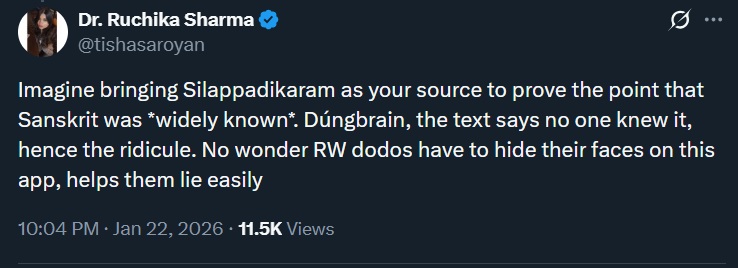

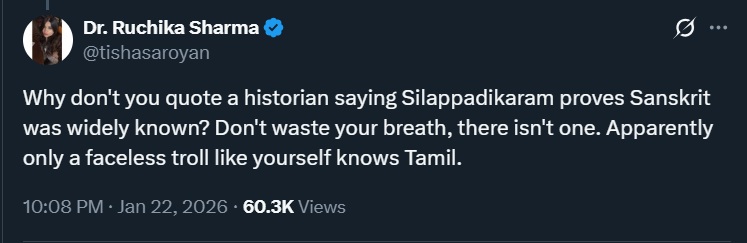

Rather than engaging with the evidence, Sharma dismissed the argument outright, demanding that a historian be quoted to “prove” that Silappadikaram shows Sanskrit was widely known, adding that “there isn’t one”, and resorting to personal derision.

That response reveals a fundamental scholarly error.

Primary Evidence Does Not Require Permission

Silappadikaram contains a well-known verse:

தேற்றா மாந்தர் ஆரியம் போலக்

கேட்டார்க்கெல்லாம் பெருநகை தருமே

The verse states that when people speak Sanskrit (Āriyam) without proper knowledge, it becomes a source of ridicule to listeners.

The logic of the verse is inescapable. Ridicule presupposes comprehension. One cannot mock incorrect Sanskrit unless there exists an audience capable of recognising correct Sanskrit. The text assumes not rarity, but familiarity, both with the sound of the language and with standards of linguistic competence.

This is not a modern interpretation imposed on the text. It is the internal logic of the verse itself.

By demanding a modern historian’s endorsement instead of engaging with the primary source, Sharma commits a category error. Historians interpret evidence; they do not grant evidence its validity. A contemporaneous literary source does not cease to be evidence because a present-day academic has not tweeted about it.

History is not decided by citation politics.

Silence Is Not Refutation

Sharma’s claim that “there isn’t one” historian who says Silappadikaram proves Sanskrit was widely known is an argument from silence. Even if accepted at face value, it proves nothing. Absence of explicit articulation in secondary literature does not negate the implications of primary texts, especially when those implications are reinforced by independent material evidence.

Indeed, Sanskrit’s presence in Tamilakam is not inferred from literature alone.

Inscriptions and Institutions Contradict the Gatekeeping Myth

Medieval Tamil history offers overwhelming corroboration. Pandya kings such as Sundara Pandya authored works in Sanskrit. Rajendra Chola and Kulottunga I patronised Sanskrit learning extensively. The Pandyas maintained a Sanskrit academy at Madurai dedicated to advanced scholarship.

More decisively, inscriptions of the Chithiramezhi Sabha, a powerful Vellalar (non-Brahmin) mercantile and agrarian guild, routinely open with Sanskrit ślokas. Their Tamil inscriptions explicitly describe themselves as ‘செந்தமிழ் வடகலை கற்றுணர்ந்து’ – proficient in both refined Tamil and northern learning (Sanskrit).

These are not Brahminical priestly records. They are guild inscriptions. They demolish the claim that Sanskrit usage was confined to a closed caste circle.

A language systematically used in royal courts, guild charters, public inscriptions, and literary satire cannot simultaneously be “barely spoken” or socially inaccessible.

Strawmen and Personal Attacks Are Not Scholarship

Notably, the counter-argument by TS Krishnan never claimed that Sanskrit replaced Tamil as the primary spoken language of Tamilakam. It stated, accurately, that Sanskrit was widely known, heard, understood, and cultivated across sections of society, alongside Tamil.

By reframing this as a demand for proof of “common people speaking Sanskrit” in isolation, Sharma constructs a strawman while ignoring the actual claim.

When pressed with textual and inscriptional evidence, the response shifts from argument to dismissal, from sources to slur. Calling a renowned author (TS Krishnan) a “faceless troll” and questioning their knowledge of Tamil is not rebuttal. It is evasion.

What makes Ruchika Sharma’s claim even weaker is her clear inability, or refusal, to engage with Tamil itself. She does not analyse the Silappadikaram verse, does not explain its meaning, and offers no alternative reading of the Tamil lines cited. Anyone with even basic familiarity with Tamil literature would immediately see that the verse assumes an audience capable of recognising correct and incorrect Sanskrit. By skipping the Tamil entirely and instead demanding approval from “historians”, Sharma is making sweeping claims about Tamil society without demonstrating any working understanding of Tamil texts.

When someone who claims to be a historian ignores a clear Tamil verse, dismisses carved inscriptions, waves away Sanskrit academies in Madurai, and still insists that Sanskrit was “always” locked inside Brahmin homes, the issue is about her credibility. When argument collapses into derision and gatekeeping, it becomes clear that what is being defended is not history, but a narrative. And on the evidence, that narrative does not survive scrutiny.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.