The disaster of a film called Parasakthi, directed by Sudha Kongara, have reignited debates around Tamil identity, anti-Hindi politics, and the ideological legacy of the Dravidian movement. While the film positions itself as a politically conscious narrative engaging with the Hindi imposition question, it selectively presents history, omitting crucial aspects of EV Ramasamy (EVR/Periyar)’s own documented positions during the 1965 anti-Hindi agitation.

The omission does not seem to be accidental, but that of politically convenience.

What EVR Said In 1965 – And What The Film Avoids

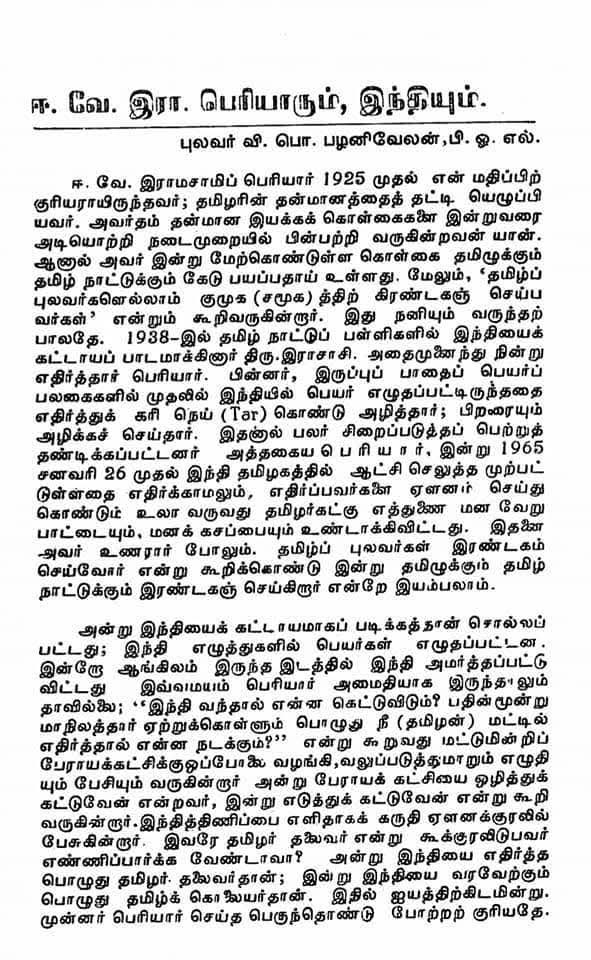

During the second anti-Hindi agitation in January-February 1965, student-led protests swept Tamil Nadu, eventually escalating into statewide unrest. While present-day Dravidian narratives often portray EVR as an unambiguous ideological force behind the agitation, contemporaneous records indicate a more complicated and controversial stance.

EVR Supported Hindi

EVR is on record questioning the logic of opposing Hindi when other states had accepted it. In responses published at the time, he reportedly asked: “What harm will Hindi cause? When thirteen states have accepted it, how can you alone oppose it?” These statements drew sharp criticism from Tamil scholars and activists who were at the forefront of linguistic resistance.

The Tamil journal Thenmozhi, edited by Devaneya Pavanar and Perunchithiranar, published sustained rebuttals to EVR’s position. Scholar Pulavar VP Palanivelan, writing in the same period, reportedly dismissed claims that EVR could be considered a Tamil nationalist leader, calling such portrayals misleading.

Students As “Rowdies”: EVR’s Characterisation Of The Agitation

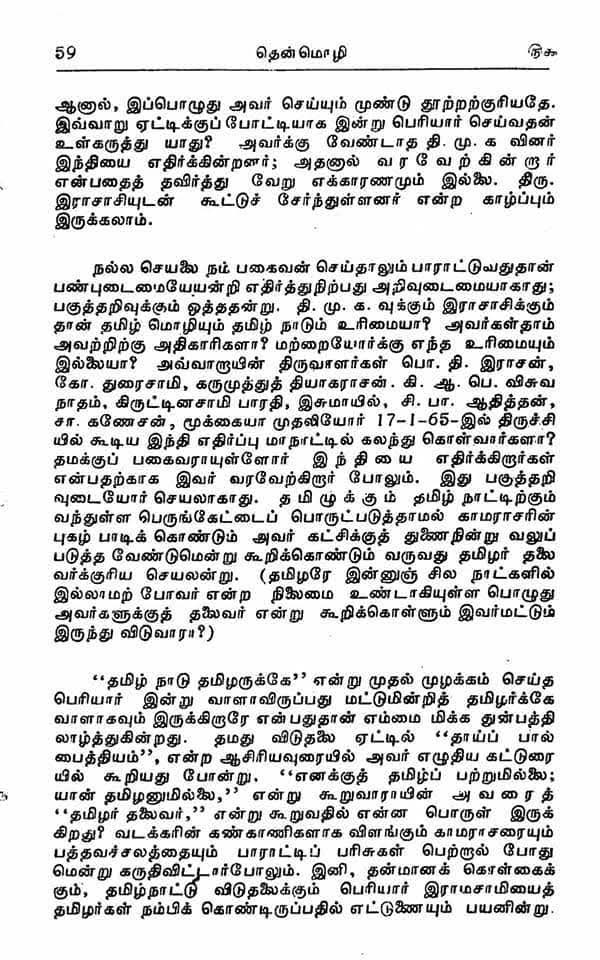

In a 1965 Pongal special issue of Kurinji, edited by Nedumaran, EVR was asked about the reasons behind student unrest. According to K.P. Neelamani’s book Thanthai Periyar, EVR attributed the agitation not to Hindi imposition but to what he described as governmental weakness and the spread of indiscipline and “rowdyism” among students.

While Congress leader K Kamaraj is reported to have cautiously suggested that northern leaders viewed the agitation as politically motivated, EVR went further, openly describing the protests as a “movement of rowdies” and criticising the Congress government for failing to suppress them effectively.

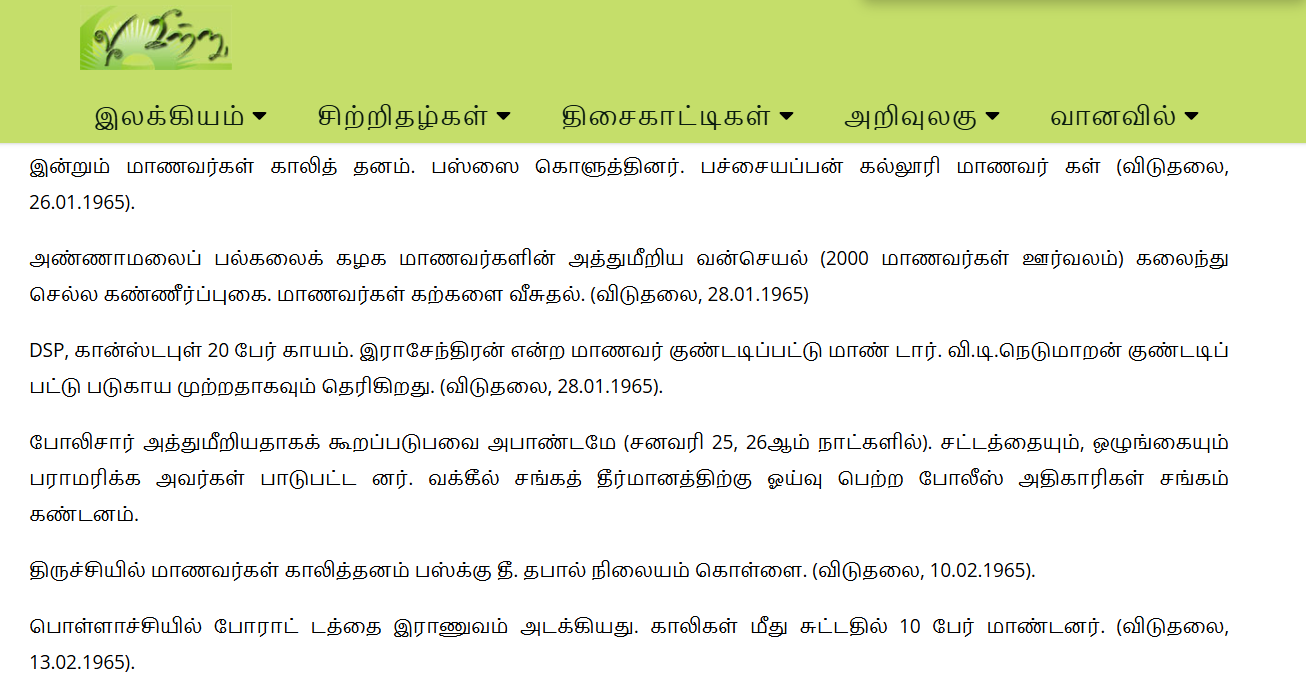

Archives of DK’s own mouthpiece Viduthalai from the period show that it was EV Ramasamy (hailed as ‘Periyar’ by his followers) who openly criticised the protesting students, referring to them as hooligans and questioning the political motives behind the agitation.

EVR’s mouthpiece had said:

இன்றும் மாணவர்கள் காலித் தனம். பஸ்ஸை கொளுத்தினர். பச்சையப்பன் கல்லூரி மாணவர் ள் (விடுதலை, 26.01.1965).

“Today also students indulged in hooliganism. They burnt buses. Pachaiyappan College students” (Viduthalai, 26 January 1965)

திருச்சியில் மாணவர்கள் காலித்தனம் பஸ்க்கு தீ. தபால் நிலையம் கொள்ளை. (விடுதலை, 10.02.1965).

“In Trichy, students indulge in hooliganism. Bus set on fire. Post office looted.” (Viduthalai, 10 February 1965)

EVR, through his ‘Viduthalai’ newspaper, supported the brutal repression carried out by the police against the protestors.

He even went to the extent of instigating violence against the protestors saying “The hooliganism has increased. Comrades! Keep kerosene in your hands ready. Keep a matchbox. When I point, you light the fire.”

This position stands in stark contrast to the moral framing of student resistance that later Dravidian narratives and now Sudha Kongara’s Parasakthi, appear to endorse.

Clash With Rajaji And Escalation Of Rhetoric

The period also witnessed a public exchange between EVR and C. Rajagopalachari (Rajaji), who argued that English, not Hindi, was the most practical link language for India and warned that developments in Tamil Nadu risked deepening internal divisions.

EVR responded sharply in Viduthalai, criticising the DMK and Tamil movement supporters and accusing them of political opportunism. Thenmozhi countered by accusing EVR of effectively aligning with North Indian dominance while attacking Tamil voices within the state. The exchanges reportedly intensified EVR’s hostility toward the agitation.

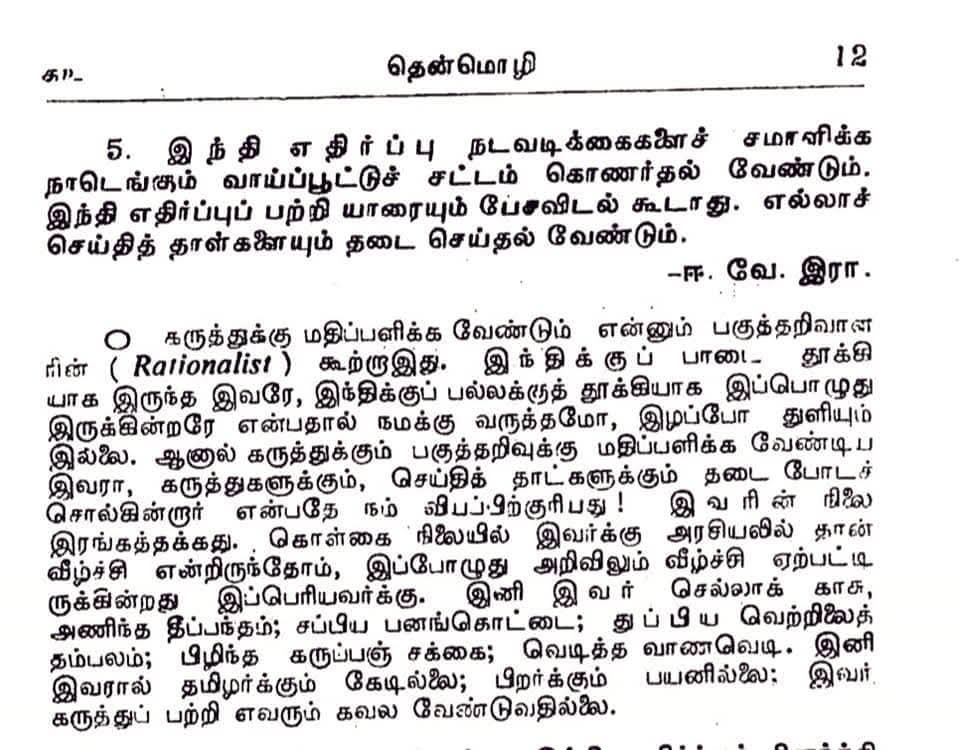

Calls For Suppression And Extraordinary Measures

According to Thenmozhi and R. Muthukkumar’s History of the Dravidian Movement, EVR went on to advocate extreme measures, including banning political parties such as the Swatantra Party and the DMK, shutting down newspapers, and imposing gag orders to prevent discussion of the anti-Hindi agitation.

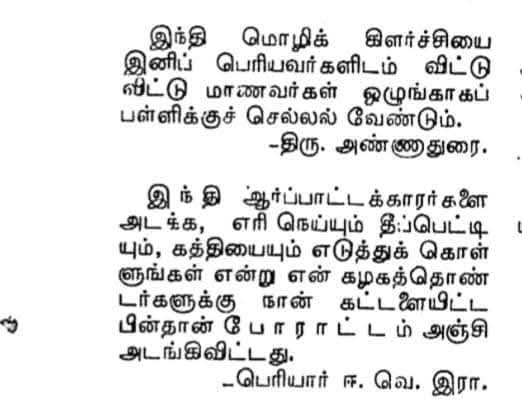

As the protests spiralled into violence marked by police action, arson, firing on students, and suicides – DMK leader CN Annadurai issued a statement distancing the party from student violence and calling for restraint.

EVR’s response, however, proved even more controversial. In a 1965 issue of Viduthalai, he reportedly claimed that the agitation subsided only after he instructed party cadres to take up incendiary materials, knives, and fire implements to intimidate and suppress protesters.

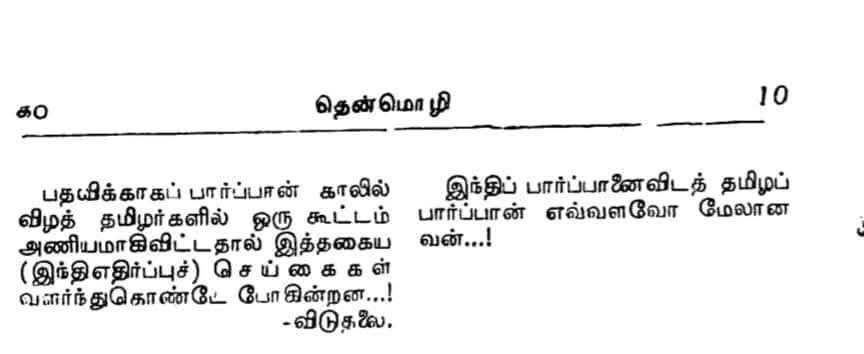

In the book “Kilarchiku Thayaaraavom! (Let’s Prepare For The Uprising)”, EVR wrote “The vandalism carried out in the name of anti-Hindi! Where is Hindi in Tamil Nadu? Which school mandated any student to study in Hindi? The newspaper scoundrels and crazy politicians who are peddling about ‘mandatory Hindi’, you people without thinking are being scared about imaginary ‘Hindi’ which doesn’t even exist!”

He further went on to say “If four hooligans had been shot in the beginning itself, all this vandalism and so much loss of life and property would not have occurred. Why is there a law? Why does police have lathis? Why do they have guns? Have they been given to kiss? What kind of a government is this!”

Bhaktavatsalam’s government, officially treated the protests as a law-and-order issue. His administration repeatedly warned against violence, threatened “stern action,” and deployed police and paramilitary forces, while blaming opposition parties like the DMK and Left groups for large-scale destruction of public property.

There are no official documents to prove that at any point Bhaktavatsalam publicly used the language attributed to him in the trailer. Transferring EVR’s words onto a Congress leader is a clear attempt to sanitise and distort EVR’s actual position.

Rejection Of Tamil Sentiment Itself

Beyond the Hindi question, EVR repeatedly criticised Tamil emotionalism. In a 1967 Viduthalai article dated 16 March, he warned the public against those who, in his words, sought to “survive by exploiting Tamil sentiment,” dismissing slogans about protecting Tamil or sacrificing one’s life for the language as deceptive tactics aimed at misleading ordinary people.

Cinematic Convenience

Sudha Kongara’s Parasakthi engages with the symbolism of anti-Hindi resistance while excluding EVR’s own scepticism, denunciations, and calls for suppression during the 1965 agitation. By doing so, the film seems to reinforce a streamlined political narrative rather than engaging with the historical record in its entirety.

This form of cinematic storytelling – selective, sanitised, and ideologically aligned that serves present-day Dravidian politics by preserving a morally consistent lineage, even if that consistency requires erasing inconvenient facts.

This article is based on an X thread by SundarRajaCholan.

Subscribe to our channels on WhatsApp, Telegram, Instagram and YouTube to get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.