With the Tamil Nadu 2026 elections approaching, a long-standing historical claim has resurfaced in political discourse: that early Dravidian political movements, starting with the Justice Party, heroically abolished an unjust colonial-era mandate that made Sanskrit a prerequisite for higher education, particularly medicine.

This narrative, presented as a cornerstone of the “Dravidian Model” of social justice, is being circulated vigorously on social media and in speeches. However, a detailed examination of historical records and the evolution of the claim itself reveal a story not of a single decisive act, but of a potent political myth that has been refined and amplified over decades.

The Evolving Story: Four Versions of a ‘Historic’ Achievement

The claim has not remained static. It has morphed through several iterations, each adding new layers and specifics:

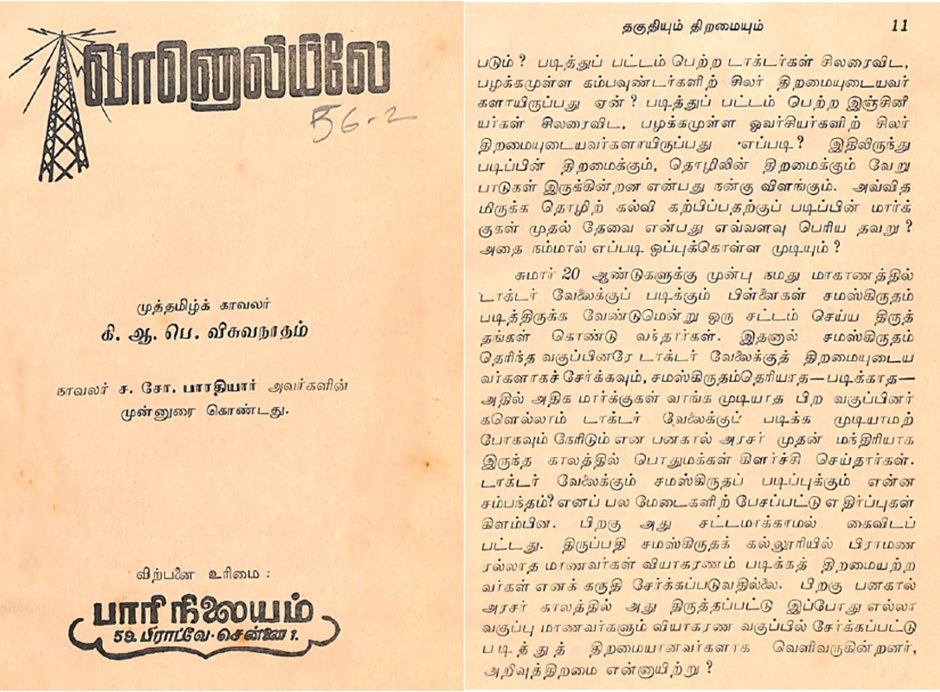

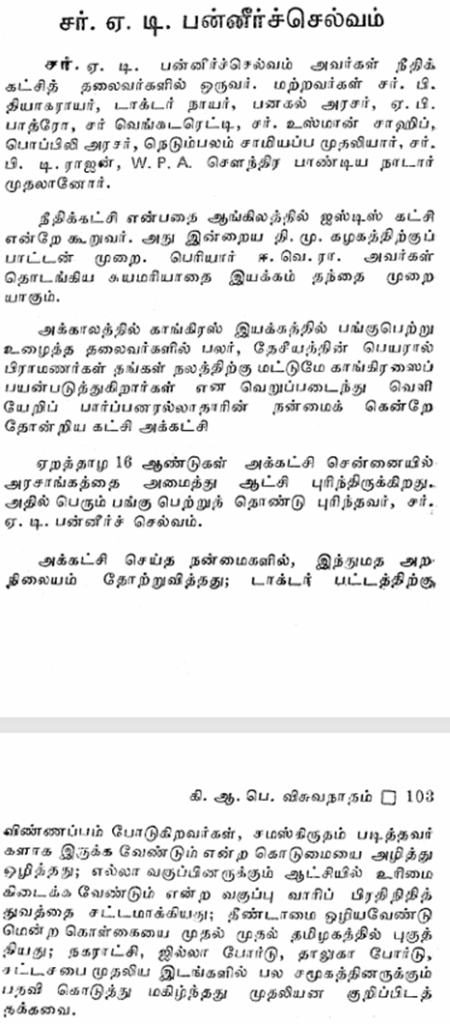

The Original Speech (1947): Justice Party leader KAP Viswanatham, in a 1947 speech, stated that in the 1920s, the Madras Presidency government planned a law to make Sanskrit compulsory for medical studies. He credited public protests and the Justice Party government under Chief Minister Panagal Raja with forcing the dropping of this proposed law.

The Published Account (1984): Decades later, in his 1984 book எனது நண்பர்கள் (My Friends), Viswanatham shifted the narrative. He stated that the Justice Party had “abolished the injustice” of having Sanskrit as a prerequisite for applying to a medical degree, moving from a thwarted “plan” to an actual abolished “injustice.”

The Anecdotal Expansion (2015): During the Justice Party centenary celebrations, DMK researchers like Wallajah Vallavan popularized a more personal anecdote. They cited a biography of Viswanatham by “Mugam” Mamani which claimed he personally approached Panagal Raja to secure a medical admission for a Justice Party leader’s son who didn’t know Sanskrit. The Raja, in response, is said to have dispensed with the Sanskrit requirement altogether.

The Broadened Mandate (2015-16): Another version that emerged during the centenary claimed Sanskrit was mandatory for all higher education. It specifically cited a Government Order (G.O. 2123, dated 08.12.1925) by Education Minister A. P. Patro, which allegedly allowed people to become “Tamil Pandits” without studying Sanskrit.

These versions collectively build the powerful political memory: that Dravidian forebears fought and dismantled a Sanskrit-centric gatekeeping system imposed on Tamil students.

Fact-Checking the Narrative Against Historical Records

A scrutiny of available administrative reports and government orders tells a different story:

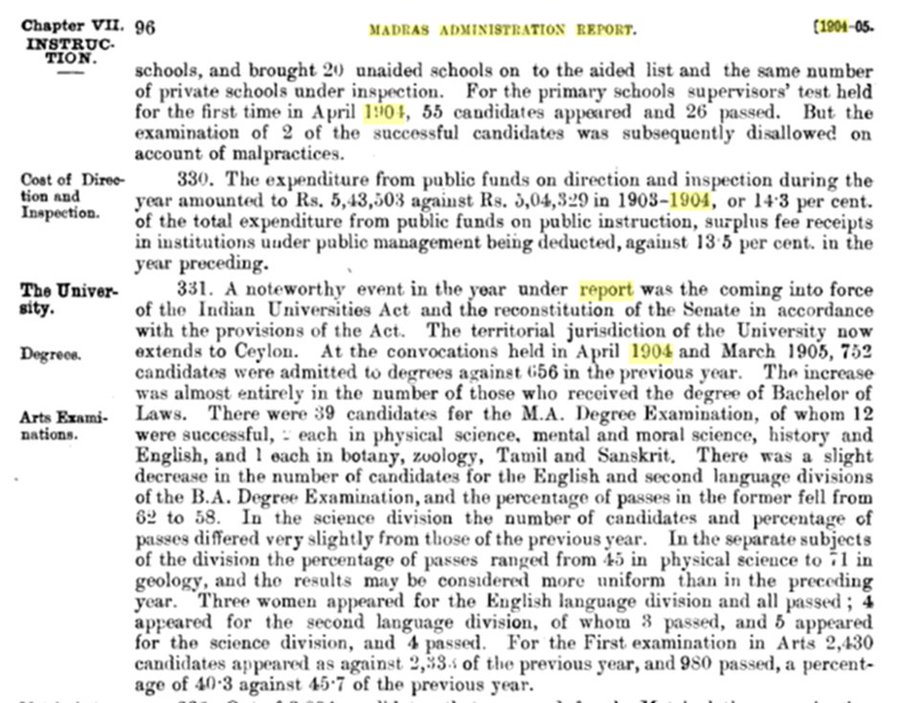

Tamil Medium in Higher Education Existed Earlier: The Madras Administrative Report of 1904 clearly states that Tamil was already a medium of instruction for the Bachelor of Arts (BA) degree. This was two decades before the Justice Party’s rise to power, contradicting the notion that they introduced Tamil into higher education.

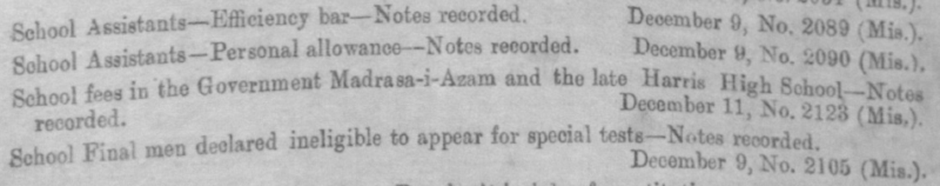

The Misrepresented Government Order: The cited G.O. 2123 of 8 December 1925, does not concern Sanskrit or Tamil Pandits. Historical records indicate this order pertained to school fee structures at the Government Madrassa-i-Azam. No G.O. from that date exists on the topic of Sanskrit prerequisites.

The Actual Focus of 1925: The significant educational reform of 1925 was the establishment of the School of Indian Medicine. This was achieved through the efforts of figures like G. Srinivasa Murthy, who convinced the colonial government to allow teaching in vernacular languages (Tamil, Telugu, etc.) for Siddha, Ayurveda, and Unani medicine. The medium of instruction for lower grades was the vernacular, with flexibility for higher grades. This was a victory for Indian systems of medicine and vernacular instruction, not specifically an anti-Sanskrit measure.

The Role of A. P. Patro: Justice Party Education Minister A. P. Patro is celebrated for his work in founding Andhra University and for the promotion of the Telugu language. There is no substantive evidence from his tenure of a sweeping order abolishing a Sanskrit mandate.

Myth-Making Versus Documented History

The persistent narrative of the Justice Party abolishing a compulsory Sanskrit mandate for medical or general higher education appears to be a potent piece of political mythology. The evidence suggests that Tamil was already an established medium of instruction in certain university courses well before the Justice Party’s tenure; that the specific government orders and events cited by proponents of the narrative do not, upon verification, support the claim and that the story has demonstrably evolved over 70 years, growing more specific and dramatic with each retelling.

This episode only highlights how the issue was weaponized for political mobilization. In the arena of identity politics, the streamlined myth often holds more power than the nuanced reality, serving as a foundational parable for Dravidian political ideology.

Baskar is a finance professional having keen interest in current affairs and Indian culture.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.