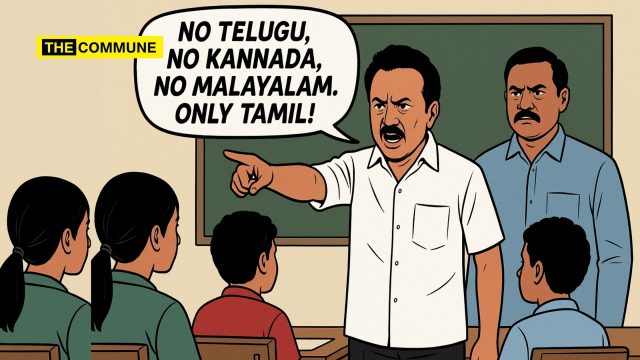

The Tamil Nadu State Education Policy 2025, unveiled by Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, has ignited fresh outrage among non-Tamil speaking communities in the state. Hidden behind the lofty rhetoric of “equity” and “inclusion” lies an unmistakable reality — the DMK government has doubled down on enforcing Tamil as a compulsory subject in all schools, effectively erasing the possibility for linguistic minorities to learn their mother tongue within the state education system.

Tamil Learning Act, 2006 — Now With Tighter Grip

The policy proudly reaffirms the Tamil Nadu Tamil Learning Act, 2006, making the study of Tamil from Class 1 to 10 mandatory across all schools — whether State Board, CBSE, ICSE, or international curricula.

This is not merely a symbolic requirement. Schools must ensure that every student can speak, read, write, and comprehend Tamil. The SEP frames this as “linguistic inclusion” and “cultural integration,” but for students whose home language is Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, Urdu, or other tongues, it amounts to state-enforced linguistic assimilation.

Mother Tongue Sacrificed

While the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recommends a three-language formula allowing space for the student’s mother tongue, Tamil Nadu rejects this, sticking rigidly to a two-language formula — Tamil and English — for all. This means that in State Board schools, minority students are denied any formal opportunity to study their own mother tongue as a subject, even if it is their first language at home.

The SEP claims it will provide “bridge programmes” for migrant and tribal children. But for permanent linguistic minority communities — such as the lakhs of Telugu-speaking families in Vellore and Krishnagiri, Kannada speakers in Dharmapuri and Erode, or Malayalam speakers in Kanyakumari and Coimbatore — there is no structured pathway to retain their language academically.

Driving Minorities Out Of State Board Schools

By making Tamil compulsory while sidelining minority languages, the policy pushes non-Tamil speaking students towards CBSE and ICSE schools, where their mother tongue may still be offered as a second language. For economically disadvantaged families, this is not an option — they are forced to choose between losing their linguistic heritage or sacrificing quality education in their own tongue.

Constitutional Concerns

Article 29 of the Indian Constitution guarantees minorities the right to conserve their language, script, and culture. Education in one’s mother tongue is not just a cultural preference — it’s a constitutional safeguard. The DMK’s strict language policy raises serious questions on whether it violates this spirit, if not the letter, of the law.

Political Motives Disguised As Cultural Pride

The DMK frames this as a measure to protect Tamil identity and “integration with the local community.” But critics argue it is part of a political project to homogenise the linguistic landscape of Tamil Nadu — diluting the presence of long-established minority communities who have lived in the state for generations.

The Bottom Line

The Tamil Nadu State Education Policy’s two-language formula isn’t about inclusion — it’s about compulsion. For hundreds of thousands of Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam, and other minority students, it means their own languages will be absent from their classrooms, their textbooks, and their academic records. What the DMK calls “integration” may in practice become linguistic erasure.

If the government truly respected linguistic diversity, it would give minorities a genuine choice — not force them to assimilate through education policy.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.