The NCERT has undergone a complete transformation, stripping away the long-standing Western-centric, Marxist lens and infusing the curriculum with a more rooted Indian perspective. The new approach highlights India’s own civilizational ethos, includes relatable real-life examples, and connects students across all regions and cultures of Bharat. Gone are the outdated Marxist frameworks that often painted India as a mere subject of Western analysis. Instead, the curriculum now reflects indigenous values and historical depth. This sweeping reform feels nothing short of a cultural goldmine rich in tone, grounded in heritage, and far more relevant to students today.

Here are a few standout examples from the revised NCERT Class 6 Social Science book textbooks :

Establishing The Civilizational Identity Of India

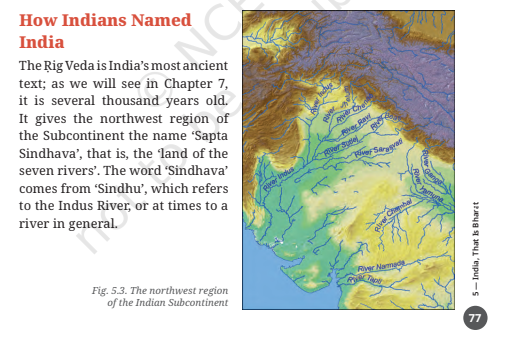

This chapter offers students a rooted and authentic introduction to how ancient Indians named their land. It begins with the Rig Veda, the oldest known Indian text, which refers to the northwestern region of the subcontinent as Sapta Sindhava — meaning the “Land of the Seven Rivers.” The term ‘Sindhu’, from which ‘Sindhava’ is derived, referred to the Indus River or rivers in general.

The chapter further explores how the Mahābhārata, one of India’s greatest epics, mentions several ancient regions that correspond to present-day locations — such as Kāshmira (Kashmir), Kuru (Haryana), Vanga (Bengal), Prāgjyotiṣha (Assam), Kaccha (Kutch), and Kerala, showing how deep-rooted and ancient India’s regional identities are.

Importantly, the chapter references names for the entire subcontinent such as ‘Bhāratavarṣa’ and ‘Jambudvīpa’, both found in texts like the Mahābhārata and Vishnu Purāna. Bhāratavarṣa is explained as “the country of the Bharatas,” with Bharata being a prominent Vedic tribe and later a royal lineage. The term Jambudvīpa referred to a larger geographical concept within ancient Indian cosmology.

Ancient Scientific Wisdom:

Chapter 1, titled Locating Places on Earth, opens with a striking quote from Aryabhata (circa 500 CE), who described the Earth as spherical and situated in space. It’s inspiring to see such early scientific thought take center stage in the curriculum.

It quotes, “The globe of the Earth stands in space, made up of water, earth, fire and air and is spherical…. It is surrounded by all creatures, terrestrial as well as aquatic. – Aryabhața (about 500 CE).”

Environmental Awareness In Ancient Texts:

Chapter 3 begins with a verse from the Atharva Veda, which clearly articulates ancient Indian concern for nature and climate. It’s a compelling reminder that environmental consciousness isn’t a recent or Western concept it has deep roots in Indian civilization.

The quote reads, “Free from the burden of human beings, may the Earth with many heights, slopes and great plains, bearing plants endowed with varied powers, spread out for us and show us her riches!… The Earth is my mother and I am her child. Atharva Veda, Bhūmi Sūkta (‘Hymn to the Earth’)”

India’s Prime Meridian – Madhya Rekha:

A fascinating insight from the “Don’t Miss Out” section reveals that India had its own central meridian, known as Madhya Rekha, which passed through Ujjain. This city was a historic hub for astronomy, home to scholars like Varāhamihira 1,500 years ago. Such details are rarely highlighted in mainstream education, making their inclusion here a powerful move to reconnect students with India’s scientific legacy.

“What North? What South? It’s all Bharat”:

The curriculum promotes a unified cultural identity that transcends regional divisions, reinforcing the idea of one civilizational Bharat. This slaps the divisive propagandist.

The book reads, A few centuries later, ‘Bhārata’ became the name generally used for the Indian Subcontinent. For instance, in an ancient text called the Vishnu Purāņa, we read: uttaram yat samudrasya himādreścaiva dakşiņam varşam tad bhāratam nāma … “The country that lies north of the ocean and south of the snowy mountains is called Bhārata.” This name, ‘Bhārata’ remains in use even today. In north India, it is generally written as ‘Bharat’, while in south India, it is often ‘Bharatam’.”

Understanding The Name “India”:

The term ‘India’ has Persian and Greek roots, originating from the Sanskrit word Sindhu (Indus River). The Persians pronounced it as ‘Hindu,’ and eventually the Greeks adapted it to ‘Indos.’ Meanwhile, traditional names like Bharat, Aryavarta, and Sapta Sindhu reflect indigenous continuity.

Highlighting Indigenous Scholars:

The work of archaeologist B.B. Lal and research into the Indus-Sarasvati civilization showcase how scholarship rooted in Indian soil brings a deeper, more authentic narrative. This marks a shift from earlier histories written through colonial or detached academic lenses, moving towards what many see as true civilizational justice.

The book reads, “The most ancient civilisation of India, known variously as the Harappan, Indus or Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation, was indeed remarkable in many ways. … [It showed how] a well-balanced community lives – in which the differences between the rich and the poor are not glaring…. In essence, the Harappan societal scenario was not that of ‘exploitation’, but of mutual ‘accommodation’. – B.B. Lal”

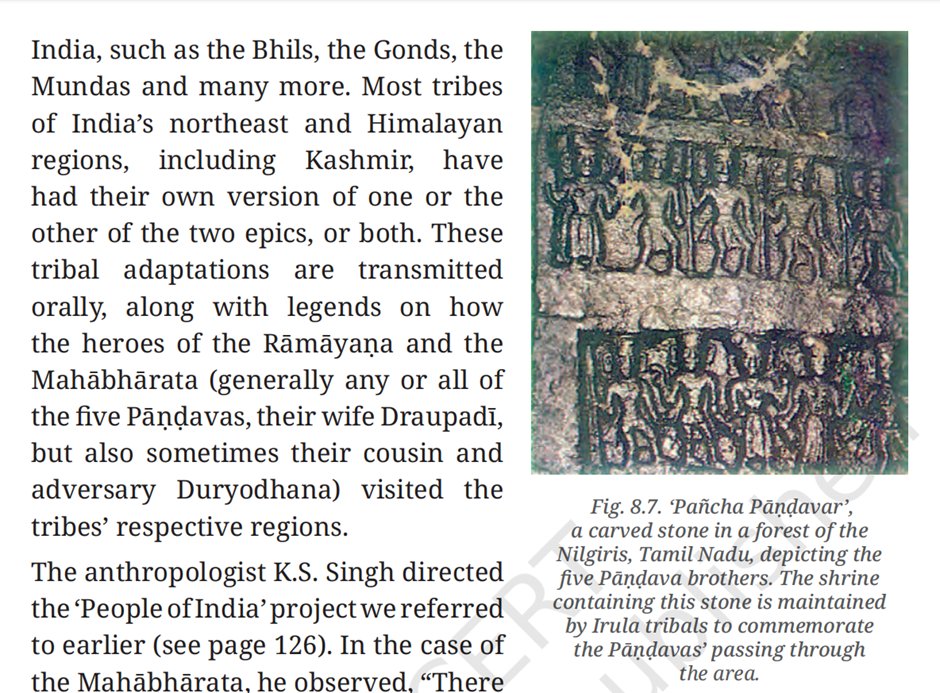

Tamil Nadu’s Civilizational Connection:

One example speaks volumes: Irula tribals in Tamil Nadu have preserved the story of the Pandavas through stone carvings. This contradicts narratives that claim Tamil Nadu is culturally disconnected from the rest of India. The real question arises who is truly disconnected from India’s heritage? The tribals who preserve it, or the Dravidianists who deny it?

Quoting Thiruvalluvar On Family Ethics:

Referencing the Tamil sage Thiruvalluvar, renowned for the Tirukkural, adds depth and inclusivity. His writings on family values, governance, and ethics are timeless and deeply relevant.

The book quotes, “Love and dharma are the flower and fruit of family life. -Tiruvalluvar”

Democracy and Epics:

The Mahabharata is cited in the chapter on grassroots democracy an excellent way to illustrate political thought emerging from ancient Indian texts. Beyond highlighting Bharat’s civilizational identity, the new NCERT textbooks also embrace global voices—such as that of Rigoberta Menchú Tum, a K’iche’ Maya activist from Guatemala, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and advocate for human rights and gender equality. Her inclusion reflects a spirit of global solidarity, inclusivity, and the shared values of justice and equality across cultures.

In the “Grassroots Democracy – Part 1 Governance CHAPTER 10” it quotes, “rājānam dharmagoptāram dharmo rakshati rakshitah” “The ruler protects dharma and dharma protects those who protect it.” The Mahābhārata.

“There is no peace without justice; no justice without equality; no equality without development; no democracy without respect to the identity and dignity of cultures and peoples.” Rigoberta Menchú Tum”

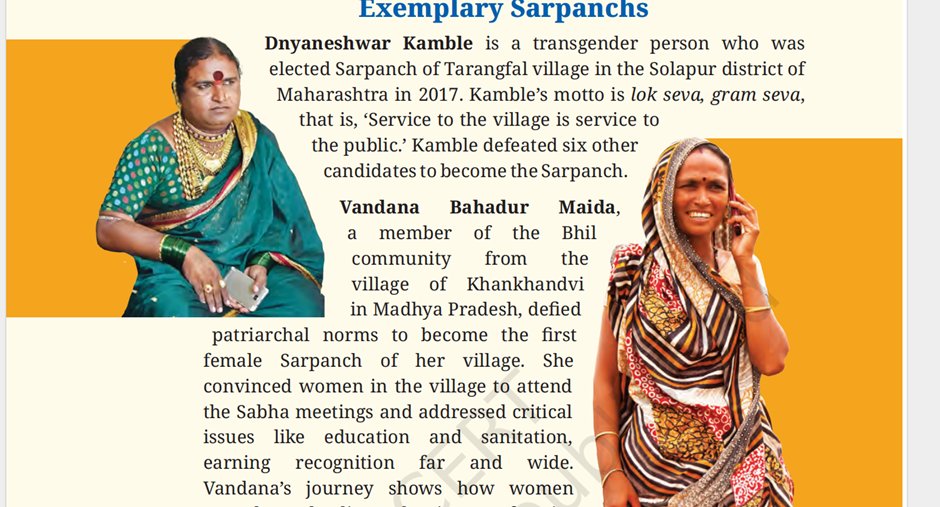

Representation Rooted In Reality:

Instead of glorifying distant figures with questionable legacies, the textbooks now feature real-life Indian icons. For example, Dnyaneshwar Kamble, a transgender person serving as a elected sarpanch in Maharashtra, and Vandana Bahadur Maida, a tribal woman who became a sarpanch in Madhya Pradesh, represent genuine inclusion.

Learning About Governance & Development:

The role of central government schemes like the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana is explained clearly. It’s shown not just as road building, but as vital infrastructure connecting remote villages to schools, hospitals, and markets.

Spotlight On Chanakya’s Arthashastra:

The ancient treatise by Chanakya is now rightly highlighted, showcasing India’s deep history of political science, economics, and administrative systems—long before colonial governance models emerged.

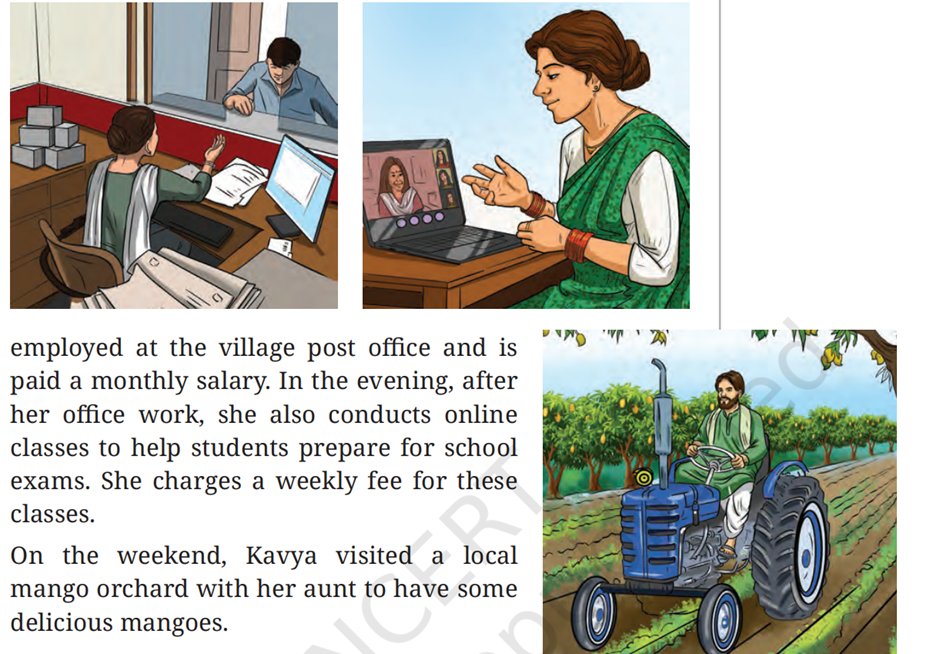

Cultural Authenticity In Representation:

Visual depictions challenge stereotypes: women in sarees working professionally, showing that traditional attire doesn’t imply backwardness. It’s a subtle yet powerful correction to outdated portrayals.

A Shift In Economic Perspective:

The economics chapter no longer demonizes wealth creation through a Marxist lens. Instead, it quotes Kautilya’s Arthashastra: “The root of prosperity is economic activity.” It encourages students to see economic growth as vital to dignity and opportunity, not as inherently exploitative.

Celebrating Regional Contributions:

In a nod to inclusivity, brands like Nandini (Karnataka), Aavin and Kevi (Tamil Nadu), and a detailed lesson on Amul are featured along with the role of Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel and Gujarat’s contribution. It’s a well-rounded narrative that honors India’s diversity.

No Woke BS

The chapter titled “Family and Community” (Chapter 9) opens with a quote by Tiruvalluvar, setting the tone with a civilizational lens:

“Love and dharma are the flower and fruit of family life.”

This in itself is a bold departure from Westernized frameworks that often sideline dharma and traditional values.

The text emphasizes the family as the most ancient and fundamental unit of Indian society, not just a social construct but a civilizational pillar.

It distinguishes between joint families and nuclear families, with a clear inclination towards valuing the joint family system, which reflects India’s deep-rooted intergenerational bonds and responsibilities. A traditional joint family is shown sitting together — grandparents, parents, and children.

Left’s Oppressor Vs Oppressed Caste Propaganda Dismantled

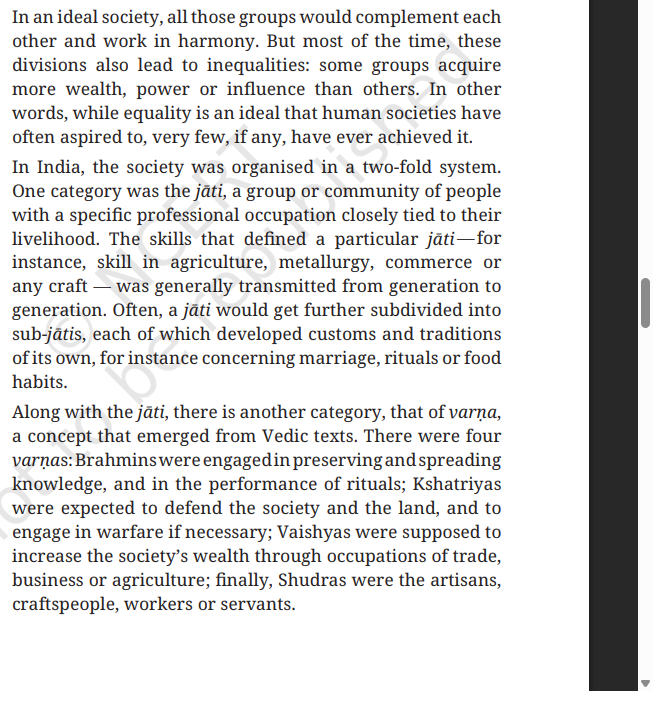

The textbook offers a balanced, decolonized view of the Jāti and Varṇa systems, portraying them not as tools of oppression but as frameworks for social harmony and functional specialization. It explains how Jāti evolved around hereditary occupations—such as agriculture, metallurgy, or crafts—where skills were passed down through generations, forming tight-knit, culturally rich communities. The Varṇa system, rooted in Vedic texts, categorized society based on duty and role, not hierarchy—Brahmins for knowledge, Kshatriyas for protection, Vaishyas for trade, and Shudras for service. Unlike the usual Marxist lens of oppressor vs. oppressed, this chapter highlights how these groups complemented each other in a cooperative civilizational order, offering students a truthful and dignified understanding of India’s social structure.

Calling Out Islamist Rulers For Who They Really Were

The revised NCERT Class 8 Social Science textbook offers a more candid account of the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal rule, highlighting numerous examples of religious intolerance and violence—a significant shift from previous editions. It portrays Babur as a fierce and merciless invader who massacred entire populations, erected “towers of skulls,” and enslaved women and children, despite also being described as intellectually curious. Akbar’s reign is characterized as a mixture of cruelty and religious accommodation, referencing his brutal massacre of 30,000 civilians during the siege of Chittorgarh and the destruction of temples, even while later promoting a more inclusive approach. Aurangzeb, meanwhile, is shown as motivated by both political and personal religious reasons, issuing edicts to demolish temples, including those at Banaras, Mathura, and Somnath, along with Jain and Sikh places of worship.

The book also details how Alauddin Khilji’s general, Malik Kafur, targeted major Hindu centers such as Srirangam, Chidambaram, Madurai, and potentially Rameswaram. It acknowledges that temple destruction during the Sultanate era stemmed from both loot and iconoclastic zeal. The imposition of jiziya on non-Muslims is also portrayed more critically—described as a means of public degradation and a push toward conversion to Islam. This starkly contrasts with older NCERT narratives, which largely omitted or downplayed these violent episodes, focusing instead on administrative achievements and general political transitions.

A Cultural Cartography Of Bharat

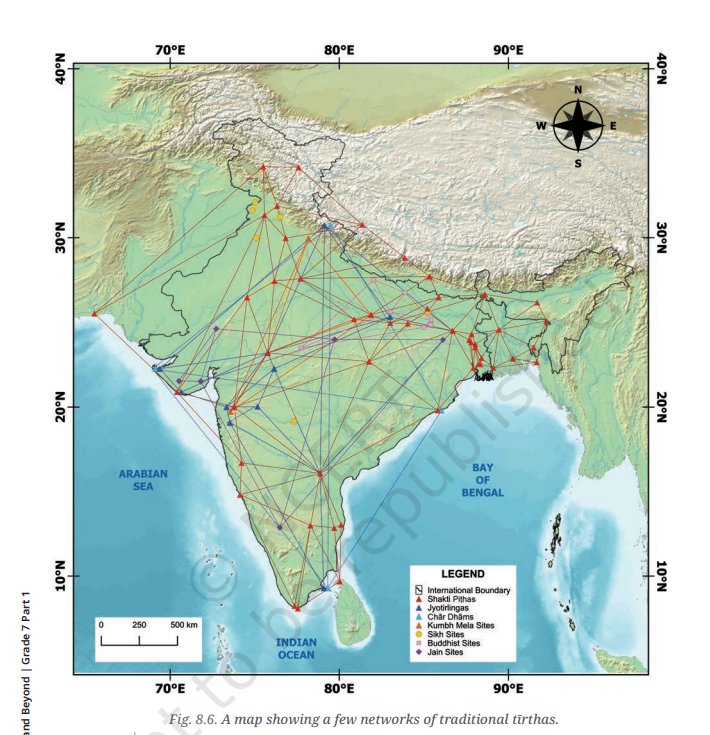

Finally, a particularly noteworthy addition appears in the Class 7 Geography textbook, where India’s deep-rooted religious and spiritual heritage is meaningfully represented. The textbook features a map highlighting sacred sites such as the Shakti Peethas, Jyotirlingas, Char Dhams, Kumbh Mela locations, as well as important Sikh, Buddhist, and Jain pilgrimage centers. This is a significant shift from the earlier trend where Marxist historians, influenced by colonial frameworks, often downplayed or reinterpreted India’s native traditions, sometimes even hijacking Indian cultural traits to credit external Abrahamic influences. In contrast, this map offers students a clear and respectful representation of India’s own civilizational and spiritual geography.

In summary, the revised NCERT textbooks offer a much-needed reset anchored in India’s own history, knowledge systems, and lived experiences. By replacing outdated colonial and Marxist narratives with content that’s culturally authentic and intellectually enriching, this shift truly represents a refreshing and long-overdue change.

(This article is based on an X Thread By Aaraadhya Saxena and Star Boy Tarun)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.