Did you know? Back in 2006, the Congress-led UPA government under Sonia Gandhi was reportedly engaged in behind-the-scenes efforts to hand over the strategically crucial Siachen Glacier to Pakistan India’s long-standing adversary without consulting the Indian Armed Forces or intelligence agencies. This secretive move, had it gone through, would have severely undermined the sacrifices of countless soldiers who have risked and given their lives defending one of the world’s most unforgiving military outposts.

The shocking revelation came from one of the Indian Army’s most respected and battle-hardened leaders, former Chief of Army Staff General J.J. Singh. In a candid disclosure, he accused the then government of bypassing the military leadership and national security apparatus while pursuing backchannel negotiations with Pakistan over a mutual troop withdrawal from Siachen.

According to General Singh, the discussions in 2006 were held without taking the Indian Army or intelligence agencies into confidence. This claim gains further credibility as a former Foreign Secretary also later confirmed that both India and Pakistan were indeed working on a proposal for demilitarizing the glacier region that same year.

General Singh questioned the rationale behind such a move, especially when Indian soldiers had never once asked the government to pull back despite the extreme weather, treacherous terrain, and frequent casualties. He emphasized that India holds a significant advantage in high-altitude warfare, making Pakistan the side struggling more in Siachen, not India.

What stunned him most was the complete lack of consultation. General Singh stated that even as Army Chief at the time, he was kept in the dark about these diplomatic overtures. He saw it as a grave insult to the memory of the soldiers nearly 890 of whom, including officers, laid down their lives during Operation Meghdoot in 1984 to secure the glacier.

He strongly condemned the Congress government’s assumption that peace with Pakistan could be achieved by simply vacating a territory so hard-won by Indian forces. If this was their definition of peace, he said, it was nothing short of delusional.

This incident stands as a stark reminder of how political miscalculations can risk national security and disregard the courage, sacrifice, and commitment of India’s armed forces.

In a old private TV debate General JJ Singh said, “In this particular case, we made our stand very clear. No withdrawal unless the Pakistani army agrees to authenticate on map and satellite imagery of their present position and tell their nation that they are nowhere near Siachen Glacier – there is a Saltoro Ridge between them and us. Till that time, I think we should not do any withdrawal And this is not going to work out. It will land us into a trap. We’ll be embarrassed. The nation would be embarrassed and the army would always be very very unhappy to take a task like this.”

Ex-Army General JJ Singh (a UPA appointee) reveals that then UPA chairperson Sonia Gandhi attempted to cede the Siachen Glacier to Pakistan.

She nearly got the then-PM MMS to sign the deal after being pressured by the US-Pak lobby.It was the Indian army that stalled the deal. pic.twitter.com/rtI6gSc3dl

— Rishi Bagree (@rishibagree) June 4, 2025

In his book How India Sees the World, Shyam Saran provides detailed insights into how close India and Pakistan came to formalizing a mutual troop withdrawal from the Siachen region. The plan also involved setting up a joint monitoring mechanism to oversee the area after demilitarization. According to Saran, this wasn’t the first time such discussions had occurred. Similar negotiations had taken place in 1989 and 1992 — both under Congress governments — but had failed to materialize due to unresolved disagreements, particularly on Pakistan’s side.

The earliest effort, during Rajiv Gandhi’s tenure in 1989, failed due to Pakistan’s unwillingness to agree to key terms. Another attempt was made in 1992 under Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao, focused on mutual withdrawal from the Actual Ground Position Line (AGPL), but the political leadership then decided to defer the issue to future rounds of dialogue.

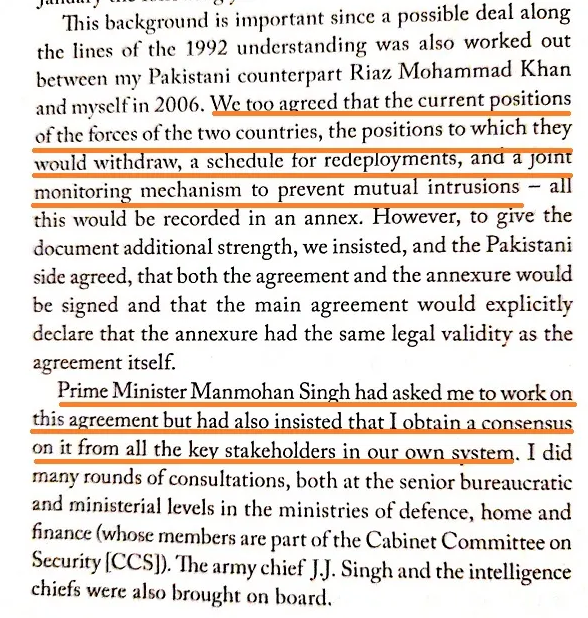

The most serious effort came in 2006, when Saran, then Foreign Secretary, and his Pakistani counterpart Riaz Mohammad Khan reached a tentative agreement under directions from the Manmohan Singh government. Saran disclosed that the draft deal even included clauses for authenticating troop positions before any withdrawal would take place — a key demand from the Indian side. Both sides agreed that the main agreement and its annexure would hold equal legal standing.

Manmohan Singh reportedly urged Saran to work toward sealing the deal, but also instructed him to secure consensus from all key stakeholders, including top officials in the ministries of Defence, Home Affairs, and Finance, all of whom were part of the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS). Despite this groundwork, the proposal failed to move forward, largely due to strong reservations from the defence establishment and security advisors.

The book read, “To give the document additional strength, we insisted, and the Pakistani side agreed, that both the agreement and the Annexure will be signed and that the main agreement will explicitly declare that the annexure had the same legal validity as the agreement itself,” writes Sharan.

“Prime Minister Manmohan Singh had asked me to work on this agreement but had also insisted that I obtain a consensus on it form all the key stakeholders in our own system. I did many rounds of consultations, both at the senior bureaucratic and ministerial levels in the ministries of defence, home and finance (whose members are part of the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS).”

According to Saran, the proposal had initially gained the support of key members of the security establishment, including then-Army Chief General J.J. Singh and the heads of India’s intelligence agencies.

The Indian Army had reportedly agreed to the draft framework, which outlined specific details such as the current troop positions of both India and Pakistan, their respective withdrawal lines, a timeline for redeployment, and a joint monitoring arrangement to prevent cross-border incursions. These technical components were to be formalized in an annexure accompanying the main agreement.

Once this draft received preliminary approval from the stakeholders, it was presented to the Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) — the country’s apex body for national security decisions — for final clearance.

However, during the CCS discussions, National Security Advisor (NSA) M.K. Narayanan voiced strong objections. He warned that Pakistan was an unreliable negotiating partner and cautioned that such a withdrawal would not only trigger political and public backlash but could also weaken India’s military posture in the region — particularly in relation to both Pakistan and China. His intervention proved pivotal. Saran notes that, surprisingly, General J.J. Singh, who had earlier supported the plan, shifted his stance during the meeting and aligned with Narayanan’s concerns. He expressed that moving forward with the Siachen deal could jeopardize national security. This change of heart effectively stalled the agreement.

Interestingly, while Defence Minister Pranab Mukherjee and Home Minister Shivraj Patil remained non-committal during the CCS meeting, they reportedly did not endorse the deal either. Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, who was keen on sealing the agreement with Pakistan, refrained from pushing back once key security officials raised objections.

Narayanan also suggested that the Siachen issue be removed from the India-Pakistan negotiation agenda entirely. Though Pranab Mukherjee is said to have later supported the idea of demilitarization, citing former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s earlier openness to such talks, the plan was ultimately abandoned due to mounting security concerns.

Saran’s revelations are not the only source confirming this behind-the-scenes episode. A separate WikiLeaks cable had previously exposed how the UPA government, led by Sonia Gandhi and Manmohan Singh, was prepared to cede control of the Siachen Glacier despite resistance from the Indian military, which warned of the long-term risks.

These disclosures underscore a troubling pattern in the Congress party’s approach to national security and territorial integrity. Had the deal gone through, India could have lost control over one of its most strategically important military zones — the Siachen Glacier, often referred to as the world’s highest battlefield, crucial for monitoring activities of both Pakistani and Chinese forces in the region.

In the end, it was the strong opposition from NSA M.K. Narayanan that prevented what could have been a major strategic misstep, ensuring that Siachen remained under Indian control.

These revelations underscore the extent to which the UPA government was willing to compromise on a highly sensitive and strategic frontier — risking a hard-won military advantage and the legacy of over 890 Indian soldiers who laid down their lives to defend Siachen during Operation Meghdoot and beyond.

(With inputs from Organiser & OpIndia)

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.