As the Communist Party of India (CPI) completes 100 years, its leaders, fellow travellers, and intellectual sympathisers are marking the occasion with celebration, nostalgia, and selective memory. Conferences are being organised, commemorative volumes released, and speeches delivered extolling the “historic contribution” of Indian Communism to workers, peasants, and democracy. Yet centenaries are not meant merely for remembrance; they are moments for serious evaluation. Political movements do not earn relevance by age alone. They earn it by outcomes, conduct, and contribution to the nation.

Over the past century, Indian Communism has consistently projected itself as the moral conscience of Indian politics the voice of the oppressed, the champion of the underprivileged, and the ideological alternative to what it dismisses as “bourgeois democracy.” It has claimed historical inevitability and moral superiority over other political traditions. And yet, after a hundred years, the communist movement today stands electorally marginal, ideologically rigid, socially disconnected, and increasingly irrelevant to India’s aspirations.

This raises an unavoidable question that cannot be brushed aside with slogans or romantic recollections of a vanished past: did Indian Communism actually serve India, or did it ultimately damage the nation’s political, economic, and social fabric?

Answering this question requires neither rhetorical hostility nor ideological prejudice. It requires an honest audit based on historical record, political conduct, and measurable outcomes. After 100 years, an ideology deserves neither automatic reverence nor automatic rejection. It deserves truth.

Not Indian in Origin, Never Indigenous in Spirit

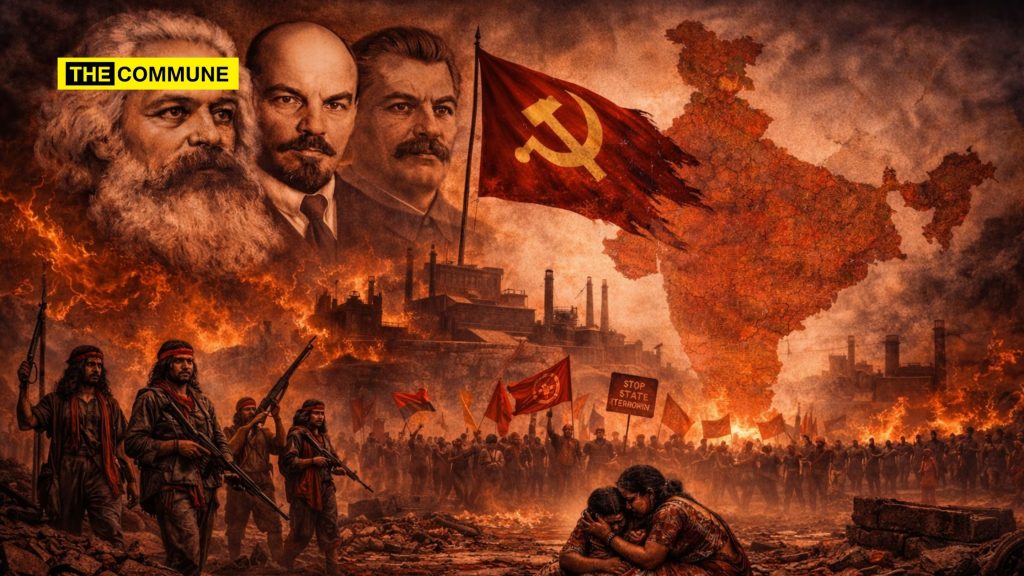

Communism did not emerge from Indian social, cultural, or economic realities. It was a European ideological product, born in the specific historical conditions of 19th-century Europe. Its intellectual foundations were laid by Karl Marx, who analysed the dynamics of industrial capitalism in Europe factory labour, wage exploitation, and the sharp divide between capital owners and industrial workers. Vladimir Lenin later adapted this theory into a model of violent revolution led by a tightly controlled vanguard party seizing state power.

Both thinkers operated within relatively homogeneous, industrial societies where economic class was assumed to be the primary identity. Their framework rested on rigid assumptions: a clear oppressor–oppressed binary, violent rupture as the path to justice, and centralised control as the solution to inequality.

India, however, was never structured this way. Indian society is civilisational, plural, and layered. It is shaped by community, region, faith, language, and tradition not by economic class alone. Historically, Indian social change has occurred through reform, accommodation, synthesis, and gradual evolution rather than the annihilation of existing structures. From Bhakti and Sufi movements to social reformers and national renaissance, India’s civilisational method has always favoured continuity over destruction.

This fundamental mismatch explains why Communism never achieved deep societal acceptance in India. An ideology built on rigid binaries could not sustain itself in a civilisation that thrives on plurality, negotiation, and organic balance. Indian society is complex and adaptive; Communism is doctrinaire and inflexible. This contradiction lies at the heart of Communism’s long-term irrelevance in India.

Ideology Above Nation: The Quit India Betrayal

Beyond its theoretical incompatibility, Indian Communism is burdened by a far more serious charge: the repeated prioritisation of ideology over national interest. The most glaring example remains its conduct during the Quit India Movement of 1942.

In August 1942, India witnessed one of the most decisive mass uprisings against British rule. The Quit India Movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi, cut across regions, castes, and ideologies. It was a moment of national unity and moral clarity. And yet, the Communist Party of India chose to stand apart from the nation.

The CPI opposed the Quit India Movement not due to any strategic assessment of India’s readiness for freedom, but because of ideological alignment with Moscow. When Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, Britain became an ally of the USSR. Overnight, the CPI reclassified the Second World War as a “people’s war” against fascism and instructed its cadres not to disrupt the British war effort. Strikes were discouraged. Protests were opposed. In several instances, Communist functionaries cooperated with colonial authorities.

While millions of Indians faced arrests, firing, and imprisonment, the CPI stood aside not because India’s freedom could wait, but because Soviet interests demanded restraint. Few episodes so clearly illustrate how Indian Communism subordinated national aspirations to foreign ideological centres.

The China War: Ambiguity in the Face of Aggression

A similar pattern re-emerged during the 1962 Sino-Indian War. When Chinese forces crossed India’s borders in Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh, the nation expected unity and moral clarity from its political leadership. What it received instead from large sections of the Communist movement was silence, confusion, and ideological sympathy for the aggressor.

The crisis exposed the deep ideological dislocation within Indian Communism. Instead of unequivocal support for India’s sovereignty, sections of the Left attempted to rationalise Chinese actions through Marxist jargon. This culminated in a split within the CPI, leading to the formation of the CPI(M), with its pro-China orientation.

Once again, when ideology clashed with national interest, Indian Communism faltered.

From Ballot to Bullet: The Descent into Armed Insurgency

Ideological confusion was damaging enough. What proved catastrophic was the gradual abandonment of democratic politics by sections of the Communist movement. From the late 1960s onwards, large segments embraced armed insurgency as a legitimate political tool. This was no longer opposition to the state it was war against the Indian Republic.

What followed was not a struggle for workers’ rights, but a prolonged campaign of violence: assassinations, massacres, landmine blasts, destruction of infrastructure, and systematic intimidation of civilians. The victims were not colonial rulers or capitalist elites, but ordinary Indians tribals, farmers, elected representatives, policemen, and daily-wage workers.

From Senari and Bara in Bihar to Dantewada, Sukma, and Jeeram Ghati in Chhattisgarh, the trail of blood is undeniable. The Dantewada massacre of 2010 alone claimed the lives of 76 CRPF personnel. The Jeeram Ghati attack targeted elected leaders. Landmines have blown up civilian vehicles in Giridih and Latehar. Entire regions have been held hostage to fear and stagnation in the name of “class struggle.”

This violence did not liberate the poor. It devastated them. It destroyed schools, roads, healthcare access, and livelihoods. It delayed development in tribal regions by decades, ensuring continued misery while insurgent leadership thrived in underground privilege.

Electoral Collapse and Ideological Exhaustion

While armed extremism represents one face of Communism’s failure, its parliamentary wing tells another story. Once dominant in West Bengal, Tripura, and Kerala, Communist parties have been decisively rejected by voters in most of India. Where they governed, their record is marked by industrial stagnation, flight of capital, politicisation of institutions, and cadre-driven intimidation.

The collapse of Left Front rule in West Bengal was not accidental—it was the result of decades of economic mismanagement, ideological rigidity, and suppression of dissent. Even today, the Left’s vocabulary remains frozen in the 20th century, unable to engage with India’s entrepreneurial, aspirational youth.

Conclusion: A Hundred Years, No Redemption

After a century, Indian Communism cannot be judged by intent, theory, or self-image. It must be judged by record. That record reveals an ideology imported from outside India, fundamentally misaligned with Indian civilisation, repeatedly subordinating national interest to foreign ideological loyalties, and turning to violence when democratic relevance declined.

This is not the story of an ideology betrayed by circumstances. It is the story of an ideology that failed because it could not adapt to India’s pluralism, its civilisational continuity, or its democratic ethos. The centenary of the Communist Party of India is therefore not a moment for celebration, but for reckoning.

After 100 years, Indian Communism has neither liberated the poor nor strengthened democracy nor safeguarded national sovereignty. It has only demonstrated one enduring truth: an ideology that places itself above the nation will ultimately damage both the nation and itself.

Dr. Prosenjit Nath is a techie, political analyst, and author.

Subscribe to our channels on Telegram, WhatsApp, and Instagram and get the best stories of the day delivered to you personally.